A REFLECTION ON AFTERLIVES OF ARCHITECTURE

SPOTLIGHT

READING, RUINS AND REUSE IN A CHANGING COLOMBO

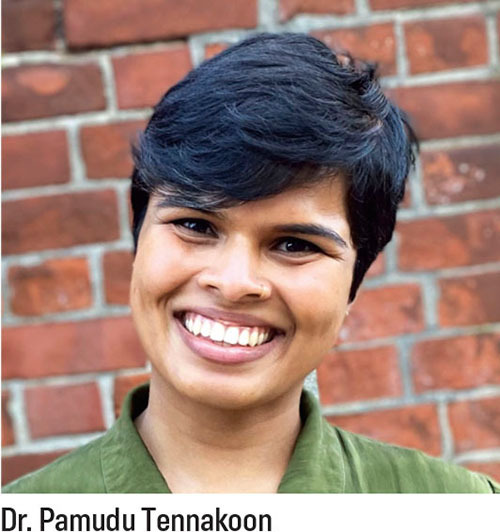

BY Dr. Pamudu Tennakoon

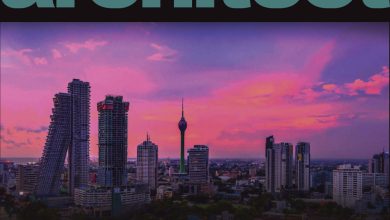

Colombo is a city that is rapidly changing. Following the end of the war in 2009, the city’s growth accelerated – almost as if making up for lost time. Despite the economic crisis, the urban skyscape appears different from year to year. With the Indian Ocean on one side and sprawling suburbs on the others, however, the city is not gifted with ample space for growth. Existing buildings have become a battleground for the future, their value measured against the continued need for land to build upon.

It is against this rapidly evolving backdrop of Colombo that, for eight weeks, a discussion seminar – a reading group – was convened on the Afterlives of Architecture at the Collective for Historical Dialogue and Memory. The participants, who gathered every Wednesday evening in Colombo 5, brought with them an interest in time and architecture stemming from wide ranging places. Personal, professional and theoretical interests intersected in that room as we connected disparate topics and examples from across Sri Lanka and the larger region.

So, what are the afterlives of architecture? As a scholar trained in architectural and art history, I organised the seminar to explore buildings and architecture beyond style and construction. Architects and architectural historians often view architecture through the lens of conception, focussing on architects, patrons, dates and movements. But what if we move beyond this moment? What if we explore buildings not merely as conceived and constructed forms but spaces that are lived in, engaged with and understood as having a multitude of lives and afterlives?

This is how most of us experience our built environments – the architecture around us – but that is often not how architecture is written about or captured. Architecture carries stories: not only of origins and demolitions but of the time in between and the journeys after. As this idea came to life during our weekly discussions, we explored questions of time, reuse, preservation and destruction. We explored notions of reconstruction and ways of accessing these lives and afterlives of architecture. Over two months our readings helped us to reimagine buildings that define our day-to-day lives.

To understand architecture, use and afterlives, it is important to begin with the familiar – the built forms we are familiar with, the ones we see, the ones we remember and the ones that matter to us. That is how this seminar began: with the buildings that came to mind when we first encountered the phrase ‘afterlives of architecture.’ As we shared during that first week, there emerged stories of forests and temples as well as of homes and architects; some lost, some still with us. This was accompanied by a reading by Lilian Chee, in which she expanded on the now defunct Tanjong Pagar Station in Singapore. In her work, Chee presented not only the history of the Tanjong Pagar Station but also the significance it held for the community – and for herself. She noted that it was the artistic engagements, the work of Simryn Gill in particular, that captured the Tanjong Pagar Station, giving this derelict structure an afterlife that extended beyond its locale as trains stopped travelling through.

As the weeks progressed, so did the central themes of our discussion. Our early seminars explored ideas of preservation, reuse and adaptive reuse. We concluded that these concepts are interlinked – it is impossible to detach heritage, preservation, conservation, or reuse from the idea of afterlives. Each of these concepts seek to extend the lives of buildings, to pause them in time. However, the dilemmas presented by preservation can also be blatant. One such dilemma is that of authenticity:

“An emphasis on authenticity has led us to believe that we can time travel, that we can experience the lives of people in the past by standing before the places they built. It has at times led us to believe that if we honor the original we might recover a lost world and its values.”

But what is authenticity? In this quote from a work titled Why Preservation Matters, architectural historian Max Page very lucidly showcases one of the fundamental misconceptions surrounding heritage and preservation. We are led to believe that if an object, space, or building is authentic – preserved authentically – it can transport us to the past, reviving a historic moment. Yet, in discussing this work through architecture, it became evident that this idea of time travel is also interwoven with nostalgia. Sitting in a previously colonised country, we cannot encounter nostalgia without delving into the concept of colonial nostalgia. When we combine authenticity in preservation with nostalgia, it creates a dangerous dialogue of yearning and the potential for these desires to actualise. In the preservation of colonial buildings, for example, is colonialism not only preserved but also venerated?

This seminar has been a space for exploration and questioning. Every search for answers has led to more questions. Having an afterlife through preservation – through a return to an authentic past – also fundamentally implies that a building, for example, has completed living a life. Thus, it doesn’t allow or account for the continued living of a building, or its natural demise. This brings us to one of the fundamental dichotomies present in the approach to the lifecycle of buildings, between Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and John Ruskin. While Viollet-le-Duc views restoration and reuse as quintessential to the lifecycle as it provides a new lease on life, Ruskin believes that architecture should be allowed to perish naturally.

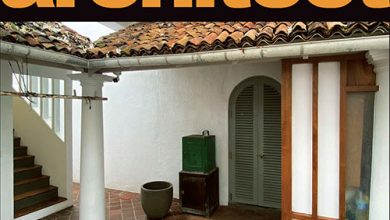

In these discussions on heritage, reuse and preservation, our conversations often returned to the Arcade Independence Square. The Arcade’s revival and the decade long effort to find its footing – from one form of a mall to another – has served as an example par excellence for us to critically engage with the space. It presents itself as a culmination of many layers of histories and a lack of reckoning with all these pasts. As Marc Herter presents, it has become a spectacle. As the Independence Arcade has become a shell for shops and restaurants, it erases many of its former uses and reverts the building to, and promotes, its original purpose as a colonial asylum – exemplifying postwar Colombo’s glorification and gentrification of colonial architecture. How might the alternate reality have looked, had the Arcade been allowed to live its life and perish?

Following discussions on attempts to save buildings and pause time, we moved to think through death of buildings – ruins, garbage, copying and iconoclasm. As buildings lead their lives, they often become ruins and later garbage. They are either made ruins through destruction or become so due to the toll of time. How do we understand what is left? Why does the debris left behind fill us with such unease and the desire to completely remove it? Ann Stoler’s seminal essay Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination alongside the work of Yael Navaro-Yashin in Northern Cyprus and Anoma Pieris in Sri Lanka, presented us with the unease of ruins and the debris of imperialism. From the heaviness of imperial ruins, garbology and the work of William Rathje returned joy and fun to our discussions as we explored what happens to building material in destruction and how we can learn from the piles of garbage we have generated across – and specifically in modern human history. Similarly, through the work of Marcus Boon, we were able to destigmatise copying – to see it as transformative. These weeks left us with questions about recycling and space. Is there space for ruins in a city?

As we conclude the seminar, we will move away from the pages and open the floor for participants to present on architectures of their choice, viewed through the lens of afterlives. Bringing in their research, and both artistic and personal practices to this short research project, I hope that we will not only learn more about Colombo, but also how value – especially social and emotional value – is generated in both the presence and absence of buildings. Ultimately, this seminar has provided a space to collectively learn and theorise the lives of buildings beyond the whitewashed walls and newly tiled floors – to the many lives they impact and the many lifetimes they live.

REFERENCES

Lilian Chee, “After the Last Train: Remainders at the Tanjong Pagar Station,” in Architecture and Affect: Precarious Spaces (Routledge, 2023).

Max Page, Why Preservation Matters (Yale University Press, 2016), 41.

Liliane Wong, Adaptive Reuse: Extending the Lives of Buildings (Birkhauser, 2017).

Marc Herter, “Development as Spectacle: Understanding Post-War Urban Development in Colombo, Sri Lanka. The Case of Arcade Independence Square,” Geographien Südasiens 7 (2017): 1–50.

Ann Stoler, “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination,” Cultural Anthropology, 23, no. 2 (2008): 191–219; Yael Navaro-Yashin, “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects: Ruination and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15, no. 1 (2009): 1–18; Anoma Pieris, “Dwelling in ruins: affective materialities of the Sri Lankan civil war,” The Journal of Architecture, 22, no. 2 (2017): 1001–1020.

William Rathje and Cullen Murphy, “Yes, Wonderful Things,” In Rubbish! The Archaeology of Garbage, 3-29 (Harper Collins, 1992).

Boon, Marcus. “Copying as Transformation.” In In Praise of Copying, 77–105. Harvard University Press, 2010.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boon, Marcus. “Copying as Transformation.” In In Praise of Copying, 77-105. Harvard University Press, 2010.

Chee, Lilian. “After the Last Train: Remainders at the Tanjong Pagar Station.” In Architecture and Affect: Precarious Spaces. Routledge, 2023.

Herter, Marc. “Development as Spectacle: Understanding Post-War Urban Development in Colombo, Sri Lanka. The Case of Arcade Independence Square.” Geographien Südasiens 7 (2017): 1–50.

Navaro-Yashin, Yael. “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects: Ruination and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15, no. 1 (2009): 1–18.

Page, Max. “Why We Preserve,” Why Preservation Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Pieris, Anoma. “Dwelling in ruins: affective materialities of the Sri Lankan civil war.” The Journal of Architecture, 22, no. 2 (2017): 1001–1020.

Rathje, William, and Cullen Murphy. “Yes, Wonderful Things.” In Rubbish! The Archaeology of Garbage, 3–29. New York: Harper Collins, 1992.

Stoler, Ann. “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination.” Cultural Anthropology, 23, no. 2 (2008): 191–219.

Wong, Liliane. “The Quest for Immortality.” In Adaptive Reuse: Extending the Lives of Buildings, 58–71. Basel: Birkhauser, 2017.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Dr. Pamudu Tennakoon