DITWAH AFTERMATH

WHEN SHOCK TESTS BUSINESS RESILIENCE

Prashanthi Cooray takes note of how Cyclone Ditwah became an unprecedented stress test for our enterprise base

Cyclone Ditwah delivered a harsh wake-up call for Sri Lanka’s enterprise ecosystem, exposing vulnerabilities in a business landscape that is still emerging from multiple crises.

When the cyclone struck in late November, heavy flooding and landslides disrupted economic activity across sectors and regions, and exposed gaps in disaster preparedness and resilience planning.

The disruption weighed heavily on micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), a segment responsible for over half of Sri Lanka’s GDP. Already under strain from the pandemic, the economic crisis and high inflation, the cyclone laid bare how susceptible these businesses are to climate driven shocks.

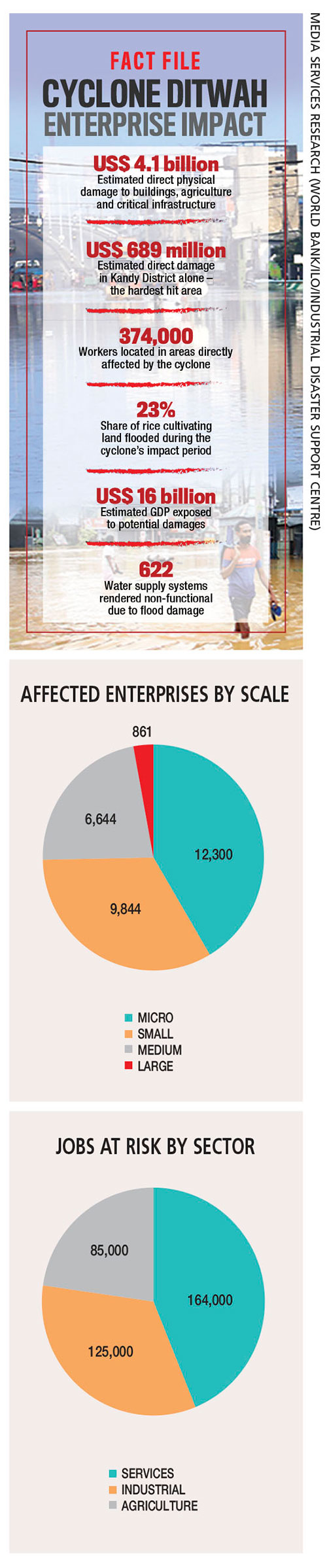

By mid-December, the Industrial Disaster Support Centre (IDSC) had received 29,649 requests for assistance from affected businesses. These included 12,300 micro enterprises, 9,844 small businesses, 6,644 medium entities and 861 large enterprises – figures that point to the breadth of disruption across business.

The heavy flooding and landslides translated these underlying vulnerabilities into tangible damage on the ground. Workshops, retail outlets, warehouses and light manufacturing facilities were inundated or destroyed, with inventories, machinery and raw materials wiped out virtually overnight.

Roughly 44 percent of the affected businesses had managed to resume operations within weeks but many others remained idle with damaged assets and disrupted inputs.

Priority and expedited loan facilities were approved for 9,628 manufacturing and export industries as part of the immediate response to support business recovery.

Alongside these measures, the government allocated Rs. 3 billion in non-repayable subsidies for damaged factories, proposing to provide up to 25 percent of reported losses immediately to the most severely affected facilities. Authorities also announced 200,000 rupees in grant assistance to help affected industries restart operations.

National and foreign contributions also played a part in reconstruction, supporting the restoration of transport links, essential services, and agricultural and market access infrastructure needed to keep businesses operational.

Insurance mechanisms began compensating losses for affected businesses and property owners, while Central Bank guidance enabled temporary debt relief, repayment moratoria and access to new credit on favourable terms.

However, financing alone could not fully offset the immediate losses many businesses faced on the ground.

Beyond physical damage to enterprises, Cyclone Ditwah led to profound labour market consequences. A preliminary ILO assessment estimated that up to 374,000 workers were located in areas directly affected by flooding and landslides, translating into potential monthly earnings losses of around US$ 48 million.

Agriculture and fisheries were among the hardest hit sectors.

Flooding affected up to 23 percent of rice cultivating land while preliminary estimates by the International Labour Organisation suggested that tea output in affected areas could decline by as much as 35 percent.

Smallholder farmers – who account for roughly 70 percent of tea production – were disproportionately impacted, particularly those operating with limited savings and minimal access to formal social protection.

Still, the story was not solely one of destruction.

The Sri Lanka Tea Board reported that most tea factories remained operational after Ditwah, helping stabilise production even as plantations recovered.

Similarly, data from the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB) show that tourism arrivals rebounded after the cyclone with numbers surpassing the previous year’s total – an encouraging sign for an industry that’s critical to foreign exchange earnings and employment.

Cyclone Ditwah exposed how vulnerable Sri Lanka’s enterprise base remains to sudden climate shocks, particularly in the way supply chains and operations can unravel within days. While recovery has been uneven and many small businesses continue to face constraints, the period that followed also demonstrated the adaptability of key sectors such as industry and tourism.

The challenge now lies in converting this experience into more durable systems of resilience and support for MSMEs. Done well, these adjustments could reinforce Sri Lanka’s long-term economic goals – including its aspiration to be a US$ 300 billion economy by 2030.