AGRICULTURE SECTOR

Climate shocks, rising input costs and volatile supply chains are squeezing the world’s food producers – and at the same time, populations are growing and diets shifting.

Green biotechnology is emerging as a practical tool kit for doing more with less. Gene edited staples that withstand heat and drought, microbial inoculants that cut fertiliser needs and proteins created through fermentation, which deliver nutrition with less land and water, are moving from pilot to practice.

GREENER FIELD AND FACTORY

Akila Wijerathna explores the role of green biotechnology in food production

The promise isn’t simply incremental efficiency; it’s a reconfiguration of how we grow and produce food so that productivity, resilience and environmental responsibility reinforce one another.

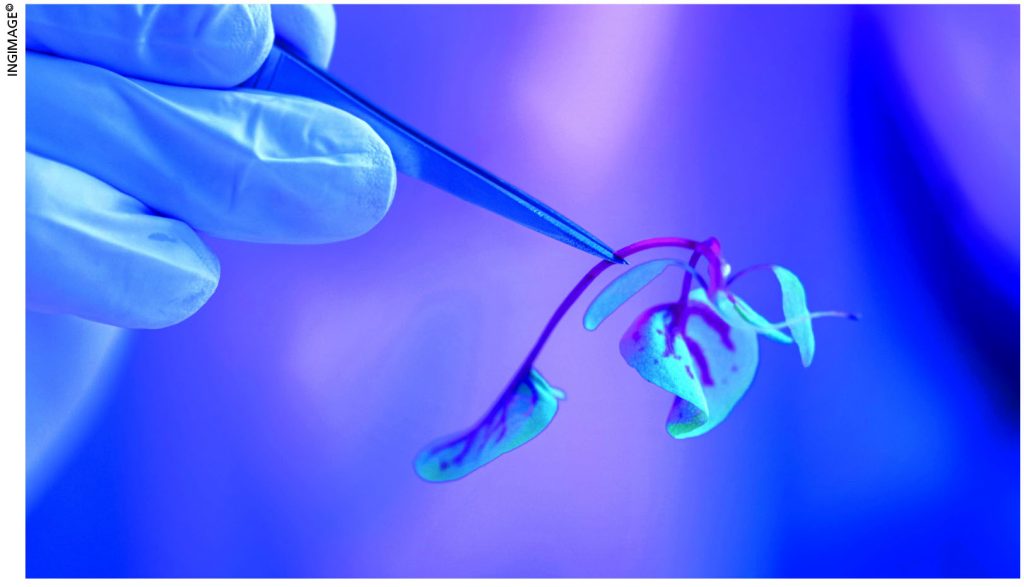

Green biotechnology refers to biological tools and platforms that are designed to improve sustainability outcomes across the food system. It spans modern plant breeding and gene editing, synthetic biology, microbial products that enhance plant performance, bio based crop protection, precision fermentation for ingredients and circular bioprocessing that upcycles waste.

It is necessary to understand the main innovation tracks, where they stand today and what must happen so they can go to scale.

Biology can move fast in the lab but farms and factories are unforgiving places. And the winners will be those who match rigorous science with farmer first economics and transparent proof of impact.

On the front line are climate smart traits. Conventional breeding has delivered major gains over decades but it’s often slow to capture complex traits tied to water use, heat tolerance and disease resistance. Gene editing and speed breeding accelerate the process by making precise and targeted changes, and compressing the number of generations needed to fix traits.

The most valuable traits that are being developed stabilise yields under stress and improve resource use efficiency – for instance, by enabling roots to mine deeper moisture or tuning nitrogen uptake and assimilation.

Early commercial entries are appearing in niche acreage and speciality crops while larger row crops are moving through regulatory gates in several markets. For growers, the calculation is straightforward.

A second surge is taking place belowground. Plants have always partnered with microbes but formulation science and DNA level characterisation now enable companies to assemble targeted consortia that deliver nitrogen, solubilise phosphorus, modulate hormones and recruit disease suppressive communities in the rhizosphere.

Modern bio-inoculants look less like folk remedies and more like engineered products. Encapsulation protects viability and supports shelf life. Compatibility testing ensures that they work alongside common agronomic practices. Field results show measurable reductions in synthetic fertiliser use and improved stress tolerance in some soil climate contexts.

Successful deployments pair products with agronomic services and soil diagnostics so that the right consortia land in the right fields at the right time.

Bio based crop protection is also evolving from concept into field tool. RNA interference sprays can silence targeted genes in pests and pathogens, bacteriophages offer narrow spectrum control of bacterial diseases, pheromones disrupt mating patterns of key insects and bio-herbicides are engineered for specific weed pressures.

These modalities promise shorter development cycles and a different resistance profile than conventional chemistry. Their specificity is both a strength and deployment challenge. Products must be precisely matched to local pest biotypes and integrated into existing pest management programmes.

Waste streams are another frontier where biotechnology converts a liability into an asset.

Agricultural byproducts such as husks, peels, straw and whey can be enzymatically or microbially upgraded into animal feed components, bioplastics precursors, organic fertilisers and speciality chemicals.

On farm or regional digesters seeded with optimised microbial consortia produce biogas while stabilising nutrients for return to fields.

This circularity logic is compelling because a ton of waste can become a source of energy and materials while the carbon intensity of farming operations declines. The economics hinge on logistics and policy incentives. Moving bulky residue is costly and consistent feedstock quality is hard to guarantee without coordinated supply chains.

A closed loop farm combines improved genetics and tailored microbes with sensing, analytics and decision support. Remote sensing detects crop stress before it is visible. Soil probes quantify moisture and nutrient dynamics. Weather models anticipate disease pressure.

Green biotechnology isn’t a silver bullet. Instead, it is a set of tools that can make agriculture and food production cleaner, smarter and more resilient, when used with agronomic discipline and economic realism.

And its success can be seen in the field and factory ledger.