Samantha Amerasinghe analyses the adverse impacts of the slowdown on the world

FRAIL GROWTH GRIPS CHINA

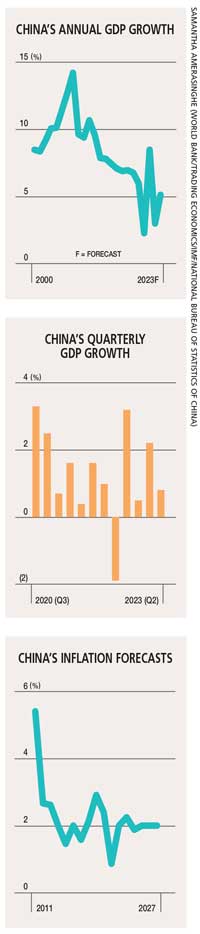

China’s poor progress this year has raised concerns that the country’s era of high growth has come to an end. Its economy was meant to drive a third of global economic growth this year; so the dramatic slowdown in recent months – accelerating at a frail pace in the second quarter at 6.3 percent year on year (due to low base effects, 0.8% quarter on quarter) has sounded alarm bells across the globe.

When much of the world underwent a major recession in 2008/09, China weathered the storm through enormous government spending that supported a global economic recovery.

It’s a different story today, what with the world being perilously close to a global recession due to a lingering war in Ukraine and the post-pandemic fallout; and a repeat of a China-led recovery seems a distant hope.

Globally, policy makers are bracing for a hit to their economies as China’s imports of everything from electronics to construction materials slide. On a positive note, this slowdown will drag global oil prices lower and have a deflationary impact.

Recent high frequency indicators such as private fixed asset investment and retail sales in China have slowed sharply, painting a picture of a bleak and faltering recovery. Meanwhile, youth unemployment is also hitting record highs. And the risk of missing its modest five percent growth target for the second year in a row is on the rise.

Even the most optimistic recovery scenario doesn’t herald a return to the 10 percent annual average growth rates that the People’s Republic has been used to for decades since Beijing embarked on economic reforms in 1978.

China’s growth ballooned from US$ 1.2 trillion at the turn of the century to nearly 18 trillion dollars in 2021, according to World Bank data. The US in contrast, which is the world’s largest economy, was a little more than double its size in 2000.

Weak growth momentum in China and global recession risks indicate that policy makers will need to do more to shore up the world’s second largest economy. There’s no quick fix or silver bullet in sight however, and Chinese authorities face the daunting task of trying to keep the country’s economic recovery on track while holding unemployment in place.

Weak growth momentum in China and global recession risks indicate that policy makers will need to do more to shore up the world’s second largest economy. There’s no quick fix or silver bullet in sight however, and Chinese authorities face the daunting task of trying to keep the country’s economic recovery on track while holding unemployment in place.

They are likely to roll out more stimulus measures including fiscal spending to fund expensive infrastructure projects, provide increased support to consumers and private businesses, and relax some government policies in relation to the property market.

But they’re also cognisant of the growing debt risks and structural distortions that could surface from an overly aggressive stimulus package.

Much will depend on how Beijing adapts to the structural challenges facing the economy and the impact of President Xi Jinping’s new priorities.

According to economists, China’s economy will slow down to between two and five percent over the coming years. Some experts argue that the country no longer needs to grow at 10 percent annually to keep pace with the developed world.

It has had a tumultuous ride since the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in March 2020 – with repeated crackdowns on the private sector and supply chain mayhem damaging investor confidence.

To add to China’s woes, its population declined in 2022 for the first time in 60 years, raising concerns about the nation’s future workforce.

The current ratio of 16 elderly people for every 100 workers is set to double by 2025 and then double again to 61 by 2050, partly due to family planning policies that limited most families to a single child in the past.

With an ageing population comes slower productivity and the large labour force that fuelled China’s low-cost industrial base is shrinking rapidly.

Furthermore, China has been replaced by India as the most populous country in the world. This comes amid an accelerating shift by many multinationals to move their manufacturing operations to other parts of Asia such as Vietnam, Malaysia, India and Bangladesh.

Prior to 2008, productivity growth averaged 2.8 percent; but since then, it has slowed to only 0.7 percent annually, leaving many corporations overleveraged.

China can ease the pain by raising the official retirement age to 65 for both men and women or automating more manufacturing by building upon its advanced digital infrastructure to help maintain industrial productivity.

New priorities are the order of the day. Xi is focussed on high quality growth with an emphasis on resilience to outside pressure (i.e. less reliance on export driven growth and a focus on driving domestic consumption) and more equal distribution of wealth – a far cry from the ‘growth at all costs’ mantra pursued by previous post-reform leaders.

This current slowdown will also influence the geopolitical power balance.

Although China’s dream of surpassing the US as the world’s chief superpower appears less inevitable, maybe slower growth is what it needs for a more equitable and sustainable path forward.

This content is available for subscribers only.