It’s hard to believe that corporate sustainability has been around for about 20 years – and yet, what do we have to show for it? What achievements in terms of impact on people and the planet? Perhaps sustainability becoming a mainstream topic in the corporate world is the only achievement…

Ernst & Young (EY) Australia recently reviewed corporate sustainability and found it to be highly wanting. Its review targeted modern sustainability professionals and challenged them to be better, as well as more collaborative and thought-provoking in terms of making a real science based impact on the planet.

NEW MOVES TO SAVE THE EARTH

Sustainability needs a reality check – Kiran Dhanapala

Its analysis compares the growing number of organisations and initiatives involved in corporate sustainability such as the United Nations Global Compact, Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) and so on – with various indicators of the health of the biosphere such as the Living Planet Index (LPI), atmospheric concentration of CO2 and ocean acidification levels.

While it does not go so far as to attribute a causal relationship, the analysis is meant to inspire debate and interest in sustainable development.

The EY report traces the historical events that led to the evolution of sustainability – including the UN Global Compact that was initiated in 1999 by then Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan. It was a first time private sector initiative on sustainable development but has been criticised since the Global Compact’s growing membership has never been required to be sustainable.

This report highlights a trend in corporate sustainability where enforcement of deadlines is poor and there’s little self-regulation. EY also illustrates how typical corporate sustainability units function with between one and six staff members who attempt to meet multiple expectations in the organisation, which include internal advocacy, target setting, annual sustainability reporting and stakeholder engagement.

The challenge facing these sustainability practitioners is that the size of the unit and their numbers are not proportionate to the scale of the problem. Much of their time is spent advocating internally as to why sustainability is (still) important.

EY argues that all this results in incrementalism with little incentives for transformative and disruptive changes. And that incremental sustainability is no longer tenable, given the enormity of the risks facing Earth.

Instead, we need to define how sustainable businesses must be and by when, and how planetary boundaries should be observed with a view to long-term restoration. This means knowing what environmental resources are used by a business – including its value chain, the planet’s limits on these resources and what operational parameters need to be maintained to keep this balance.

To enable this shift, there needs to be more access to scientific information on planetary boundaries especially in relation to specific industry inputs and outputs. Better yet, get country specific information on particular species extinction and biodiversity loss too.

While data is important, the pursuit of it shouldn’t divert attention from enabling the sustainability strategy to make a real impact.

A commitment to be sustainable must be reflected in organisational culture and the leadership rather than only the sustainability unit or department. It must also reflect a country’s urgent priorities especially in the face of extreme challenges as seen in Sri Lanka today.

In Sri Lanka, support for community level cultivation, and the storage and distribution of food and medicines, are urgent needs that can be supported by corporates in their respective stakeholder communities.

Challenging corporates to set the bar high must be done by sustainability professionals themselves – though it’s not always easy – given that they are multidisciplinary entities. The professionals must organise themselves to form a community, sharing common goals and principles.

With this must come a stricter code of conduct for sustainability professionals to challenge themselves to do better, question more and be truly transformational. It will also strengthen moving away from greenwashing and incrementalism. What’s required is a culture of collaboration and comradeship that aids what is needed urgently for the future.

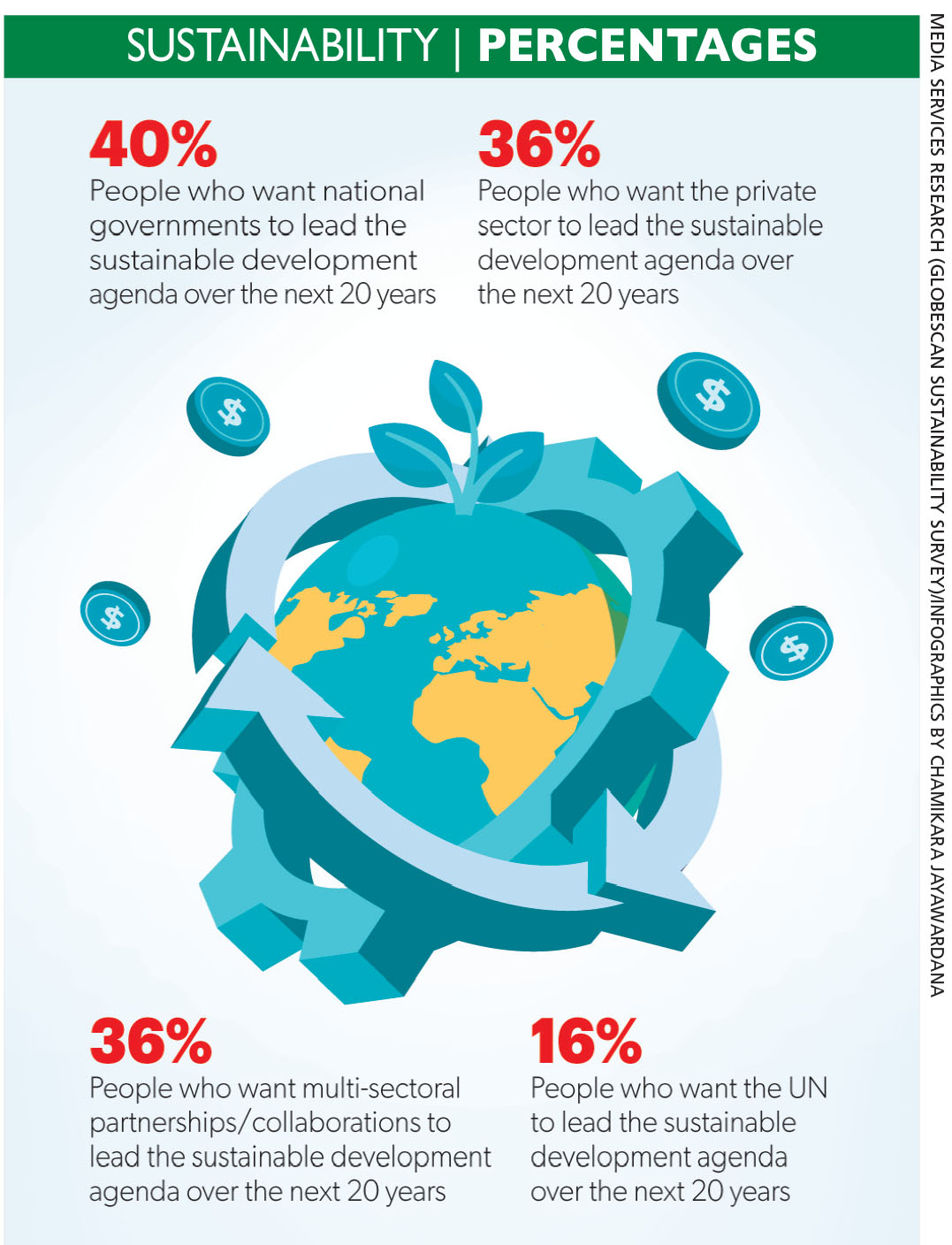

Learning how to be more impactful in the next 20 years implies organising and assessing our work better. The role of independent assessments, developing and trying alternative models for corporate sustainability, and sharing lessons learnt are also useful.

Instead of spending an inordinate amount of time reporting on sustainability progress, it would make more sense to use those valuable hours to create a transformative impact. The next 20 years will make or break the planet and our actions will result in a shared epiphany.

So how would you want to be remembered, if at all?

This content is available for subscribers only.