Sri Lanka negotiated its 17th IMF agreement, a 48 month arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) of approximately US$ 2.9 billion. The country had defaulted for the first time in April this year as a result of being perpetually caught in the crosshairs of major powers’ rivalry.

BLUEPRINT FOR PROSPERITY

Taamara de Silva writes in favour of collaboration between the two sectors

Vulnerabilities have grown owing to inadequate external buffers and an unsustainable public debt dynamic according to the IMF – the impact of which is most likely to be disproportionately borne by the poor.

Meanwhile, the Friedrich Naumann Foundation in a report has stressed the importance of the public-private partnerships (PPP) model in the energy sector, noting losses incurred by the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) despite its competitor Lanka Indian Oil Company (LIOC) running efficiently.

Across multiple industries, overlapping agency mandates are common; and yet, interagency coordination mechanisms are unavailable, resulting in the deployment of PPP models.

PPP is a tool that can help nations manage development projects and other services as ‘off budget expenses’ while increasing efficiency in project delivery and operations. However, selection criteria for PPPs in Sri Lanka have been traditionally based on lowest project or operational costs instead of more rigorous economic assessments.

Nevertheless, our precarious financial position demands serious and timely engagement as we negotiate a settlement with our creditors.

In the aftermath of these developments, the recent budget proposals have called for the reestablishment of a National Agency for Public-Private Partnership (NAPPP) coupled with restructuring of state owned enterprises (SOEs). It could well be a catalyst for foreign direct investments (FDI).

This initiative will also enable the identification of difficulties and complexities faced by investors in the process of investing in Sri Lanka, propose solutions to boost investments and take the necessary steps to implement these PPP projects within a set timeline.

In a report on the country’s current PPP environment and recommendations for a future public-private partnership strategy, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has identified certain glaring inconsistencies.

For instance, due to the lack of a viable PPP policy, law and implementing regulations, transactions can be initiated and implemented through contractual arrangements alone, creating serious ambiguities.

Furthermore, in the long term, the lack of a legal framework may potentially discourage private investment in such projects or disincentivise the government from pursuing such arrangements.

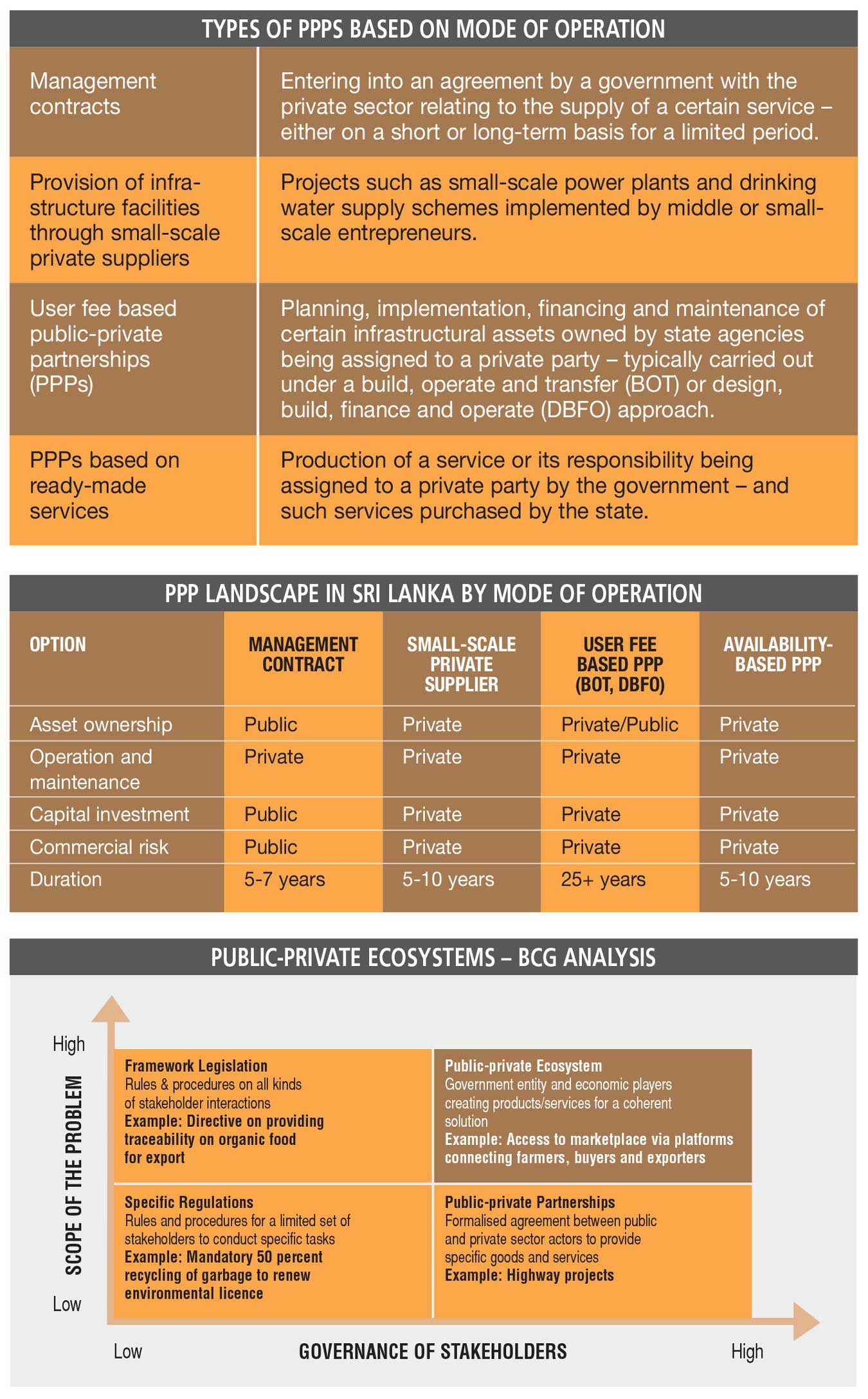

From a more theoretical standpoint, the various modes of PPP can be categorised into four types based on their modes of operation: management contracts, small-scale private suppliers, user fee based PPPs and those based on ready-made services.

In a study, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) identified ways for governments to better connect with the private sector. Traditionally, governments would engage through specific regulation that’s directed to businesses in the same industry; framework legislation with general rules for a broad set of entities; and by invitation where the state invites enterprises to collaborate on a specific project.

A fourth model, which addresses public-private ecosystems, can potentially overcome some of the challenges due to its collaborative nature and ability to engage with multiple, unidentified stakeholders.

Business ecosystems such as Apple, Amazon and Facebook provide access to a range of capabilities, scalability, flexibility and – more importantly – resilience. Such business ecosystems created by large tech businesses are a testament to the transformative potential of the model.

They can serve as good blueprints for governments that want to work out how best to engage with businesses to tackle some of the greatest socioeconomic challenges such as sanitation, environmental pollution, poverty and so on.

Moreover, modern infrastructure projects are highly complex, and require effective and cost-efficient structuring, delivery and proper financing mechanisms. This calls for an efficient risk management mechanism across the entire project life cycle, in addition to a division of roles and responsibilities among specialised players such as contractors and operators.

However, given the disparity in risk cultures across public and private sector participants, this can be quite challenging.

As Sri Lanka fights to improve its debt sustainability, attract foreign investors and improve revenue generation through improving efficiencies of SOEs, public-private partnerships are set to play a vital role in furthering these interests.

Accordingly, it is imperative that the government taps the expertise of the business community by engaging with it in a collaborative, creative and nontraditional way, to achieve progressive and sustainable reform.

This content is available for subscribers only.