Isanka Perera emphasises the urgent need for meaningful reforms to shield the disappearing middle class

THE RISE OF THE NEW POOR

“I don’t have dinner on most days so that I can feed my children two meals,” says Kumuduni. This mother of two is now the breadwinner since her husband has been laid-off by his cash-strapped employers.

She explains that groceries cost her half her wages. And fearing that deprivation of nutrition will affect her children’s cognitive development, Kumuduni tries to feed them some protein when possible.

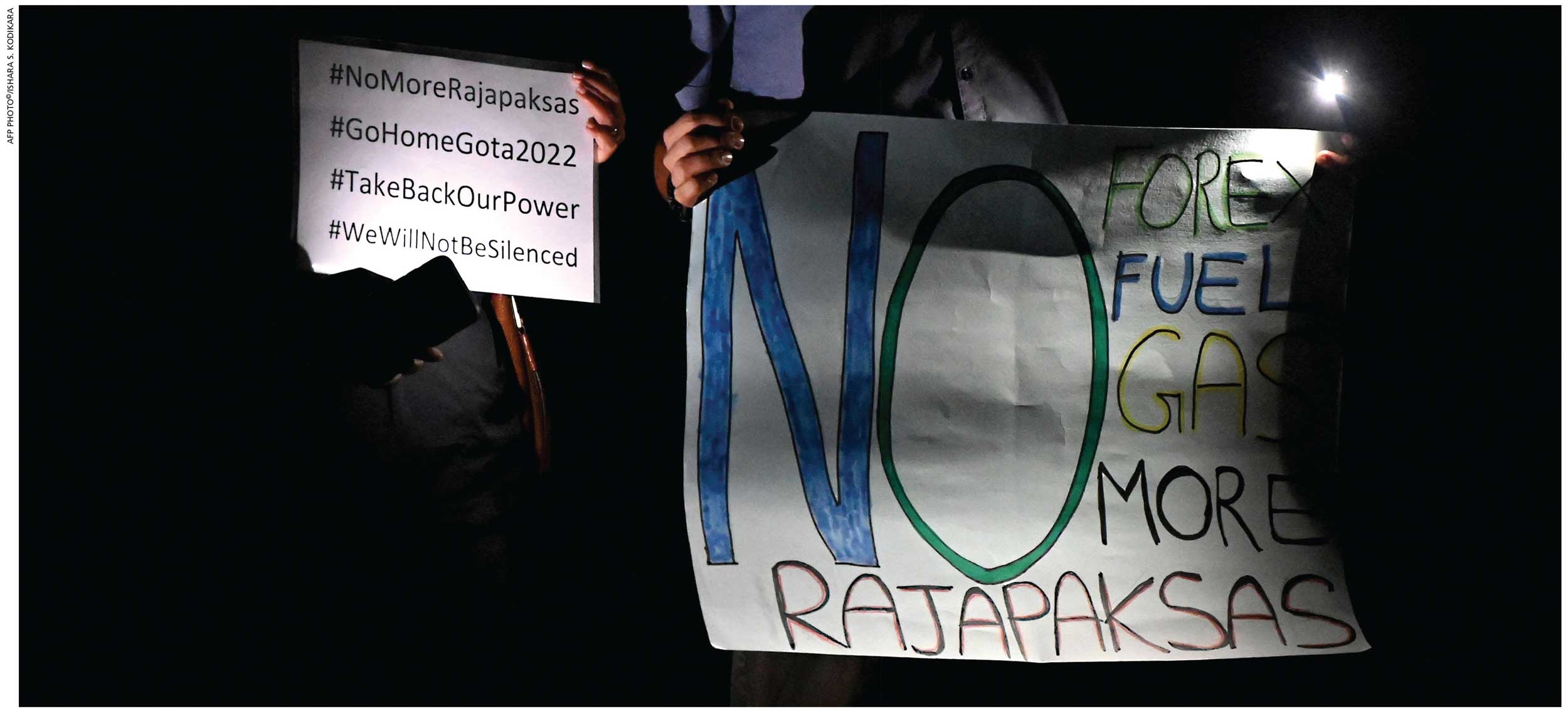

The shortage of foreign reserves has led to power cuts, medicine shortages, and long queues for fuel, cooking gas and other essentials. Soaring food prices have accelerated the rising cost of living and many Sri Lankan middle-class households are in danger of succumbing to multidimensional poverty.

After the protracted civil war ended, successive governments began working on improving the fiscal, economic and social conditions in the country. The nation had made significant progress in various human development indicators and also met some Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

Yet, many serious issues with regard to poverty and the reconstruction process persisted. When the pandemic – accompanied by disrupted supply chains, commodity price hikes and inflation – increased public and private debt, and reduced economic output unearthed pre-existing macroeconomic weaknesses, they collectively negated the progress that had been made.

According to the World Bank, the lower middle income poverty rate calculated at US$ 3.20 per person, which was 9.7 percent before COVID-19, increased to 11.7 percent in 2021 and added another 500,000 people to this category.

Economic mismanagement, the lack of foreign reserves and crippling debt means that Sri Lanka can’t afford to pay for the import of many essential items including fuel, food and medicines. With food prices soaring by more than 55 percent and non-food inflation surpassing 30 percent, Sri Lanka’s headline inflation surged to a staggering 45 percent in May.

A large portion of the country’s population lacks the capacity to cope with such a massive shock and the nationwide economic stagnation. There’s a correlation between economic inequality over three quarters of Sri Lanka’s populace and more than 85 percent of the island’s poor that live in rural areas in terms of the economic shock they face.

Many people with a per capita income that was slightly above the poverty line fell below it and this gave rise to the term ‘new poor.’

Sri Lanka is unlikely to find an easy remedy in the near and foreseeable future due to the extent of the crisis but the need of the hour is to ensure domestic stability for the necessitous population.

Even though there have been optimistic initiatives for poverty alleviation, very often these initiatives don’t reach the people living in extreme poverty or the new poor households.

In this heightened and ongoing crisis, policies are essential for poverty eradication, steady economic recovery, and other broader development issues such as employment, inequality, healthcare and education. These policies should essentially be combined to make a sustainable poverty alleviation impact.

The government must advance its targeting process and better identify the vulnerable among the population, understand their multidimensional needs, and provide support in the most effective and efficient manner.

Taking this a step further, the time has come to confront poverty through a growth conducive approach as a long-term strategy that enables families living in poverty to go through a social transformation.

We must begin growing the pie rather than sharing it in the form of continually thinning slices.

Instead of only providing short-term financial inclusion or allowance-based support, the next key challenge for the country is to create more jobs – and achieve a sustainable trajectory toward poverty reduction and shared prosperity through structural transformation.

This content is available for subscribers only.