FEATURE

ISLAND MODERNISM ANALYSING THE MODERN ARCHITECTURAL MOVEMENT OF SRI LANKA

BY Archt. Susil Lamahewa

From pre-independence to early post-independence, Sri Lanka experienced a significant transformation in its architectural landscape, shaped by the global modernist movement and adapted to the country’s unique cultural and environmental context. This period marked a shift from traditional and colonial period styles to a new architectural language that embraced functionality, simplicity and innovation. Architectural modernism in Sri Lanka was influenced by global trends, particularly those emerging from the Western world. Architects such as Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright inspired a departure from ornate designs to more utilitarian and functional structures. The socio-political climate, including Sri Lanka’s independence in 1948, also played a crucial role. There was a growing desire to establish a national identity through architecture, reflecting both modern aspirations and local traditions.

The modern architectural movement in Sri Lanka was spearheaded by pioneering architects such as Minnette de Silva, Geoffrey Bawa, Valentine Gunasekara, Dr. Justin Samarasekara, Ulrik Plesner and, less spoken of, Shirley De Alwis and Vasantha Jacobsen. These architects blended modernist principles with local materials, tropical climatic considerations and the cultural ethos of the country.

Minnette de Silva, the first female architect in Asia, incorporated elements of Sri Lankan culture, such as intricate craftsmanship and traditional motifs, into her modernist designs. Her projects, such as the Karunaratne House in Kandy, highlighted her commitment to fusing modern architecture with local heritage, focussing on modern regional architecture in the tropics. Meanwhile, Geoffrey Bawa is widely regarded as the father of tropical modernism by researchers and architectural historians. His designs such as Lunuganga, Bentota Beach Hotel (where the Bentota River formed a lagoon before flowing into the ocean), Bentota Tourist Police Station and the Institute for Integral Education in Piliyandala, emphasised harmony between built forms and the natural landscape. Bawa’s work integrated open spaces, courtyards and verandas, creating a seamless connection between interior and exterior spaces.

Valentine Gunasekara, a contemporary of Bawa, brought a stark modernist approach to the forefront with bold, geometric forms, and the use of concrete and glass. He experimented with concrete as a highly formable building material, integrating it as part of the design with a deep understanding of the strength of material and engineering. His designs, such as the Tangalle Bay Hotel, Ilangakoon House, the Bishop’s College Auditorium and Tharmaratnam House in Colombo’s Town Hall precinct were innovative for their time, with very strong curvilinear forms in concrete. His thorough detailing of projects on the drawing board solved most of the issues on site, ensuring a smooth execution during the production of his modern experimental designs.

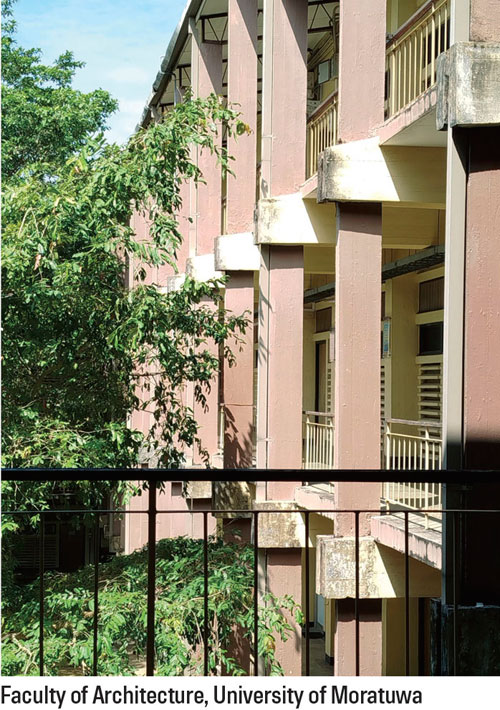

There are lesser spoken of architects who have contributed greatly to Sri Lanka’s modern architecture, including Dr. Justin Samarasekara, Shirley De Alwis and Vasantha Jacobsen. I would argue that the architecture in any country is inherently a political statement. The emergence of the modern architectural style in Sri Lanka was shaped by a few foreign educated architects, until the University of Moratuwa established its Faculty of Architecture in the early ’70s.

Dr. Samarasekara, a pioneer of post-independence architecture in the country, made significant contributions to Sri Lanka’s architectural education. His design of the Kalutara Bodhi Shrine masterfully combines religious significance with modernist aesthetics in a hollow stupa cast in concrete. The design is celebrated for its simplicity, functionality and the profound symbolism embedded in the structure. The everyday rituals performed by the public at this marvellous structure are notable. The stupa was built on the old Dutch fort Kalutara, by the river, next to a sacred Ficus Religiosa (bodhi tree).

Shirley De Alwis is best known for his design of the University of Peradeniya, one of Sri Lanka’s most iconic educational institutions. Inspired by the natural landscape of the hill country, De Alwis created a campus that blends harmoniously with its surroundings. His use of open landscape, pavilions, student hostels and the incorporation of traditional Kandyan architectural elements into a modernist framework exemplify his ability to merge tradition with modernity.

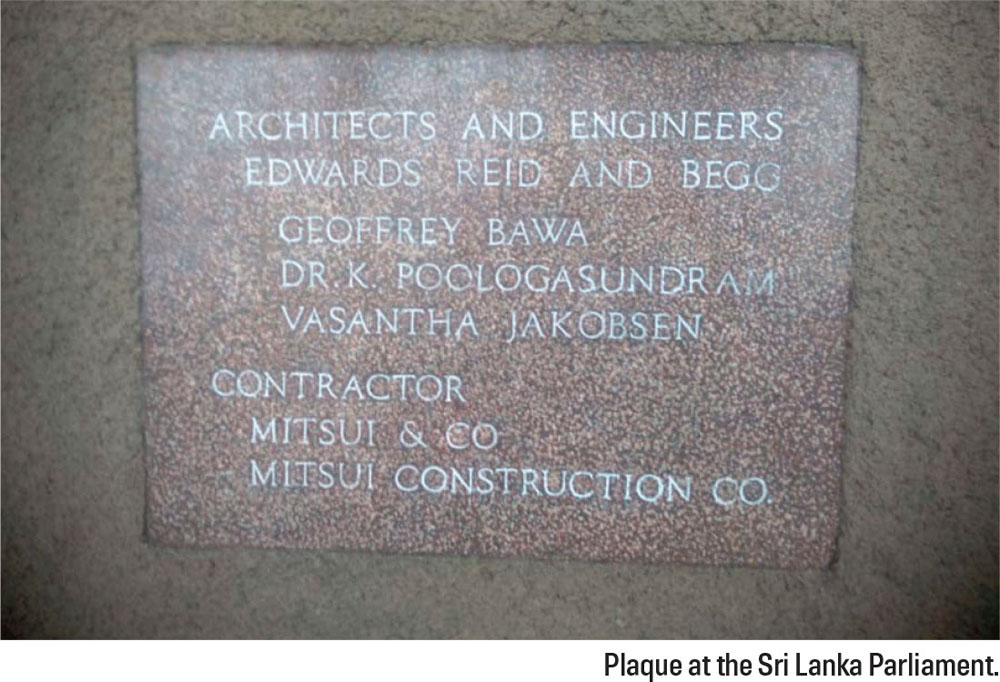

Sri Lanka’s parliamentary complex in Kotte, during President J. R. Jayawardene’s time, displayed a plaque on the wall listing the names of designers and contractors. The plaque stated that Geoffery Bawa, Dr. Poologasundram and Vasantha Jacobsen were involved in the design of the building. Jacobsen’s contribution to modern architecture in Sri Lanka reflects free forms and landscape integration. Her own house and the Matara houses showcase techniques in the use of local materials, somewhat similar to those of Ulrik Plesner who originally came to work with Minnette De Silva. In his book ‘Geoffrey Bawa: The Complete Works,’ David Robson states: “Vasantha Jacobsen’s achievements have never been fully documented and she deserves to be remembered alongside Minnette De Silva as one of Sri Lanka’s first woman architects.”

Plesner later joined Bawa and became his associate until 1967, contributing to contemporary designs. His second phase of involvement was in the Mahaweli Development Programme under then Minister Gamini Dissanayake. In 2006, Plesner came to Sri Lanka for the third and final phase, one not widely discussed within architectural circles, as a project partner with the author for a rural university funded by JDC America. Plesner was the Dormer’s eyes in Sri Lanka. During this time he was recognised by the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects (SLIA) and conferred with honorary membership of the institute. In fact, he held his first exhibition in Sri Lanka during this period.

A careful analysis of the factors considered by architects during the transition to the modernist architecture movement in the country reveals a few key areas that defined modern designs. These include climate responsive design (where architects prioritised designs that suited the tropical climate, including the use of large overhangs, courtyards and cross-ventilation), integration of nature (buildings were designed to blend seamlessly with their surroundings, reflecting a respect for the natural environment), use of local materials (such as clay tiles, timber and stone, reducing costs and enhancing cultural relevance), and simplicity and functionality (the use of clean lines, open plans and minimalist aesthetics, aligning with global modernist principles).

Impact on urban and residential architecture

During this period, modernist principles influenced both public buildings and private residences. Educational institutions, religious landmarks, government offices and urban housing projects all adopted modernist designs, showcasing a blend of functionality and aesthetic appeal. Residential architecture also underwent a transformation, with modernist homes incorporating open layouts, gardens and courtyards that reflected the island’s way of life. Parallel to this the American style emerged in the suburbs of Colombo, catering to the new middle-class as a result of urbanisation and migration during the same period.

The period from 1940 to 1970 laid the foundation for Sri Lanka’s unique architectural identity. Architects such as Geoffrey Bawa, Minnette de Silva, Valentine Gunasekara, Ulrik Plesner, Dr. Justin Samarasekara and Shirley De Alwis exemplified the movement’s capacity to balance international modernist ideals with Sri Lanka’s rich traditions and natural environment.

In conclusion, architectural modernism in Sri Lanka was a transformative era that redefined the built environment. It demonstrated how innovative approaches to design could respect both cultural heritage and the natural landscape, while addressing the demands of a modern, independent nation. These trailblazing architects created a legacy that continues to inspire and influence contemporary Sri Lankan architecture.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Anjalie Nethmini

Keshan Perera

Nimal Premachandra

Susil Lamahewa

Piyumi Amanda

Kamasarani Gamlath

REFERENCES

The Architect 50: Commemorative Volume of the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects. 2007. Stamford Lake, Pannipitiya.

In Situ. Plesner U. 2012 Narayana Press, Gylling.

Imagining Modernity: The Architecture of Valentine Gunasekara. Pieris A. 2007 Stamford Lake, Pannipitiya.

Geoffrey Bawa: The Complete Works. Robson D. 2002. Thames and Hudson, London.

The Dutch Forts of Sri Lanka. Nelson W. A. 1984. Canongate Publishing, Edinburgh, Scotland.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362955022_Modernism_in_Sri_Lanka_A_comparative_study_of_outdoor_transitional_spaces_in_selected_traditional_and_modernist_houses_in_the_early_post-independence_period_1948-1970. Perera D. and Pernice R.

The Lady Behind the Screen. Lamahewa S. and Jamaldeen S. 2024 The Architect Vol. 123 Issue 1

Valentine Gunasekara’s Search for a Just Social Fabric and a New Architecture. Anusha Rajapaksha. The Sri Lanka Architect. 1998/99. Vol. 101 No. 21.

Author’s personal conversations and notes with Ulrik Plesner in Colombo. December 2006 and August 2013.