CRISIS RESPONSE AID THROUGH ARCHITECTURE

BY Architect Shahdia Jamaldeen

In its most ideal state, the profession of architecture is one that’s based on passion and empathy – where an architect helps manifest a combination of space and sensation into a blended spatial experience that evokes emotions and lays them to rest. As a result, most laypersons view architecture as a primarily artistic vocation – especially lacking any serious impact in moments of societal calamity.

This assumption is far from accurate. Architecture and its practitioners conceive the literal building blocks of communities and ‘urbanscapes’ – shaping societies, preserving cultures, and providing spaces for nurturing good health, comfort and safety. This is no surprise, considering that shelter and sanitation is one of the five essentials needed to sustain life.

Likewise, the cycle of human habitation also manifests crises both self-inflicted through war and political upheaval, and natural disasters – which has led to research and standards that aim to either mitigate natural crisis through early prevention, provide guidelines that address real-time emergencies as they happen or look to the aftercare and reparation post-crisis.

In this sense, architecture manages to play an important role in the pre and post-situations of emergency states, which has led to the development of typologies such as crisis architecture.

For example, the widespread effects of the 2004 tsunami disaster were unprecedented as Sri Lanka had never experienced a natural catastrophe of that scale or destruction.

This led to practitioners collaborating with policy makers and organisations such as Habitat for Humanity and the United Nations to begin post-disaster housing in phases, beginning with makeshift temporary housing for those affected and then developing into mass permanent housing through situation-based guidelines.

Fast forward a few years, and architectural procedures have now come in place for early detection and resilient building through preventative methods such as the usage of resilient building materials, building on higher ground, integrating raised floor platforms and foundations as well as creating access to rooftops in moments of air rescue.

The matter of how effectively these procedures have been put into practice is an entirely different subject, which leans towards promoting national policies and the exercise of regulations by the Urban Development Authority (UDA) and National Building Research Organisation (NBRO).

Much of these endeavours rested directly on the aspect of professional volunteerism via skill and knowledge on the ground level. When considering architecture in the sphere of volunteerism, organisations such as Habitat for Humanity come to the forefront – but it is rarely that we know of any local architectural volunteer associations operating outside of the professional institution.

Therefore, it is on this basis that Architect Dumindhi Nanayakkara, who is based in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, managed to gain invaluable insight and on the ground work experience by volunteering.

Having come across the organisation All Hands And Hearts’ (AHAH) call for emergency rebuilding in the Philippines, Nanayakkara’s first instinct was to conduct her own research into the programme to determine how her skills could be put to use effectively.

The Philippines is one of the most typhoon impacted countries in the world, and the relief programme outlined the goal to provide a safe and healthy learning environment for students whose academics had been disrupted by Typhoon Haiyan.

AHAH aimed to use the volunteered skills of building professionals to develop new disaster resilient buildings for students ranging from kindergarten to Grade 6, while also engaging the local community in order to spread disaster resilient construction knowledge and increase international awareness through a diverse set of volunteers.

Once formalities and approvals had been met in August, Nanayakkara made the long journey from Rotterdam to St. Francis Elementary School in the Eastern Samar and Leyte region of the Philippines.

While some essential arrangements were provided, all volunteers had to sponsor their own travel and source items such as bedding. The situation was dire and this was reflected in the level of groundwork each person had to commit to – which made it clear what the foremost priority was in the crisis.

A typical working day consisted of all volunteers arriving on-site by 6.45 a.m., and receiving a detailed brief of work and tasks. AHAH’s primary construction implementation used cement bamboo frame technology (CBFT), which was deemed an innovative and sustainable disaster resilient system.

In collaboration with its local partner Base Bahay, AHAH provided training in bamboo construction to both the volunteers and local workers. This ensured that the community developed a sense of ownership along with longevity in terms of building maintenance.

Nanayakkara experienced this system of construction firsthand. She noted: “Why bamboo? Firstly, bamboo is already a very accessible material in the Philippines. Therefore, the act of sourcing the material itself provides livelihood to the farmers for whom it takes only three to five years to cultivate structural grade bamboo.”

“What’s even better is that its carbon footprint is 60 percent lower for each construction compared to conventional methods. More importantly, it is earthquake and typhoon resilient, which means that this construction is designed to be a long-term solution for the community,” she added.

In addition to construction work, volunteers were also expected to take on other tasks such as making spacers, painting, clearing debris off-site and performing minor repairs in the existing school building.

As a side project, the volunteers built the children a play abacus using items off the site. This enabled the children to immerse themselves safely while rousing their curiosity at the activities taking place.

Along with gaining valuable construction practice, Nanayakkara also stated that she enjoyed creating social connections with the local construction workers and observing the benefits of the programme taking place.

She said: “What was different from typical construction sites was that perfectionism didn’t have a place in this. It was about getting it done – and I needed to change my mindset to fit that. The way we build for a well-to-do client with easy access to funds and means is different to working on a rural part of an island within a tight budget.”

The realities of humanitarian work vary largely from what is portrayed on recruitment posters and media. Nanayakkara mused on this fact that getting into humanitarian work as an architect was not easy – there is competition involved and funding/donor-based arrangements can cause tension, and rightfully so.

Disaster relief, when done right, should be more than constructing a lasting building; it should also address the intrinsic needs of the community as the habitants form the lifeblood of the structures. Nanayakkara stated that there had been and still are far too many projects with good intentions that have caused more problems for communities than helped them.

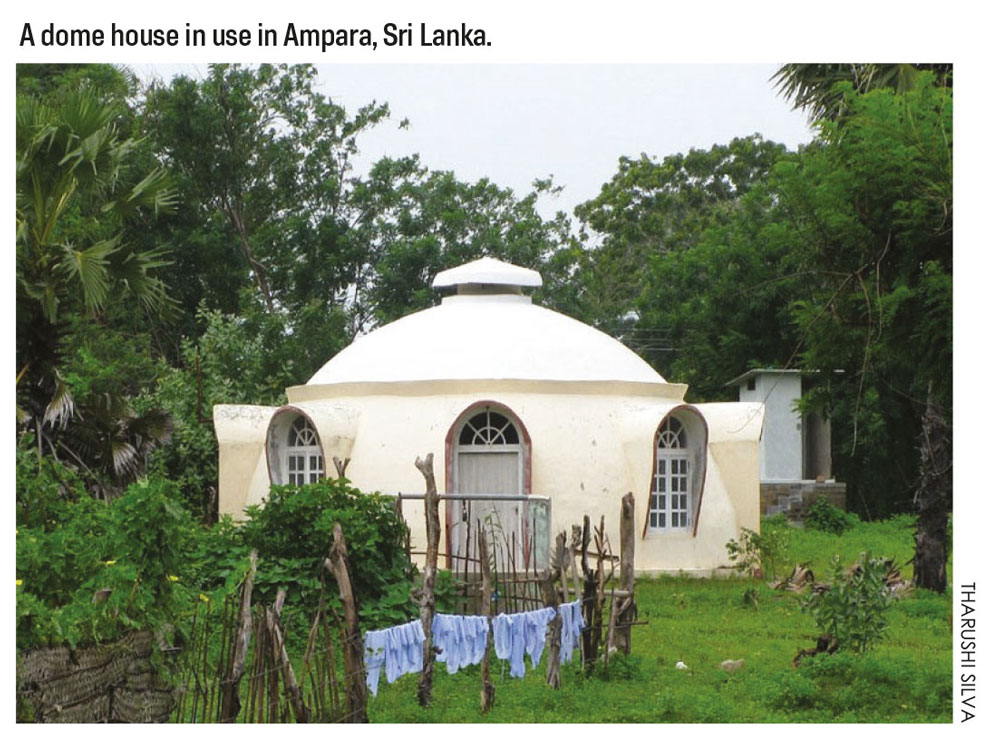

An example of this can be drawn once more from the 2004 tsunami with the housing relief project near Arugam Bay by Solid House Foundation (from the Netherlands), which featured dome-shaped concrete shell houses that were dubbed ‘balloon houses’ by the locals.

Completed in 2008, the recipients accepted the houses but many could not reconcile familiarity or comfort with the design due to it being “too foreign.”

Although the houses remained cool on the inside, the locals had many complaints including that the structures were too far inland from the sea, thus disrupting their livelihood; too cramped for their growing families; and the design did not resonate with their local vernacular (www.arkinet.com).

In contrast, the tsunami housing development in Kirinda spearheaded by Philip Bay had the developer approaching renowned Japanese Architect Shigeru Ban to design a prototype house pro bono. The design brief specifically required that it be built cheaply, using suitable local materials with appropriate timelines for R&D.

In addition to this, Ban made sure that the local Muslim settlements in the area were part of the initial design development in order to maintain cultural sensitivities. He stated: “This is the first time I’ve worked for Muslim societies so before I built the houses, I had a community meeting to find out what has to be carefully done. Depending on the generation, for example, we had to separate the man’s space and woman’s space (Dezeen).”

Similarly, Pakistan’s first female Architect Yasmeen Lari developed fortified housing in the country’s rural communities as a response to extreme climate change. Her pioneering methods in flood proof bamboo housing come at a time of devastating monsoon flooding that put a third of the country underwater.

The elevated homes with bamboo skeletons are protected from rushing water whilst withstanding immense pressure against being uprooted. Traditionally known as ‘chanwara,’ the improved single room housing design prototypes have already saved families during the flood season.

This construction only requires locally available materials such as lime, clay, bamboo and thatching. Mixed with trained local labour, the final product adds up to a cost of a mere US$ 170 (Al Jazeera).

Nanayakkara was also able to create networks with other architects and design professionals, some who had been part of the industry for many years. Hearing their stories of how they learned to adapt and navigate policies, gender discrimination and racism while trying to help has only strengthened her resolve to continue along this path.

Most importantly, she also outlined the standard operating procedure (SOP) that AHAH developed as a smart response for disaster relief:

❍ Response: Immediately after a disaster, we carefully listen to the community to identify their greatest needs, effectively begin response work and create a long-term action plan.

❍ Recovery: Where needed, we make a long-term commitment to build disaster resilient homes, schools, daycares and community centres – the hubs of every community.

❍ Resilience: By laying out and constructing disaster resilient buildings to code, we ensure that the structures are stronger and more sustainable to weather future disasters.

❍ Renewal: We live in communities where we serve and become a part of them. This leads volunteers to uncover new ways to help, which invariably brings fresh ideas and creative solutions.

Similar concepts have now begun to become mainstream with Norman Foster unveiling the Essential Homes research project in conjunction with Holcim Cement at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale.

The housing model designed by Foster is aimed at “meeting essential human needs of safety, comfort and wellbeing for displaced communities,” while showcasing the merits of Holcim’s low carbon, circular and energy efficient solutions – specifically a low carbon rollable concrete sheet serving as an external shell (Holcim).

Perhaps it is also time that we begin to create proactive groups of volunteers within the architectural profession for worthwhile long-term developments with regards to sustaining resilient communities – by building on local experience, enabling standards of procedures that meet the needs of communities from the core and building a network of pro bono services for crisis response.

It is necessary to also start creating opportunities for humanitarian volunteer access in both local and international fraternities to empower homegrown construction and foster innovation from across borders, in order to build a resilient and strong foundation both literally and figuratively.

For more information on the work and volunteer opportunities at AHAH, please scan the QR code to access its website.

RESOURCES

Virtual interview conducted with Architect Dumindhi Nanayakkara

https://www.allhandsandhearts.org/programs/philippines-typhoon-relief/

REFERENCES

https://www.holcim.com/media/media-releases/essential-homes-venice-unveil

www.arkinet.com

https://www.dezeen.com/2013/05/03/post-tsunami-housing-by-shigeru-ban/

https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2023/5/24/the-82-year-old-female-architect-working-to-flood-proof-pakistan

PHOTOGRAPHY

Architect Dumindhi Nanayakkara