ERANDUYAAYA

FEATURE

THE VALUE ADDITION OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY PRACTICE

In conversation with Archt. Diniti Wijeratne

BY Archt. Shahdia Jamaldeen

Archt. Diniti Wijeratne had always envisioned going beyond the formal bounds and scope of a traditional architect’s role. Her view stemmed from the established notion that architects are primarily professional service providers, and the sole value of the profession lay in the intrinsic value embedded in the project and ultimately in modern times’ monetary worth. It is unfortunate but as times and economic states change, so do the definition and meaning of services.

While assessing the current market opportunities for architects, Diniti accurately states that this generation of architects cannot function the same way the older cohorts operated – by relying on word of mouth, and the culture of people seeking out and approaching architects in person.

As today’s situation stands, the growing number of qualified architects is plentiful compared to the lower ratio of available projects and consulting opportunities. Diniti outlines that this situation means dealing with increasing competition within the profession, leading to members having to resort to novel and niche skill building to develop a unique edge over others.

With clients demanding more justifications for project costs and feasibility, Wijeratne confesses to having felt out of sorts in terms of business and marketing strategy within construction, realising that she could not even knowledgeably argue or defend how square footage rates were developed.

This, along with the desire to develop further skills, led to her pursuing a Project Management MBA from the Faculty of Civil Engineering at the University of Moratuwa. The decision turned out to be an eye-opener for her.

Placed within a class consisting of a colourful cross-section of professionals ranging from engineers, business owners and entrepreneurs, to bankers and corporate workers, Wijeratne was exposed to completely divergent points of view and disciplines, which eventually helped her formulate a project proposal for her course assignment.

The research and presentation required her to come up with a viable business proposal beyond her professional expertise and comfort zone, which was then to be presented to a panel of bankers, who would assess it in terms of real-time feasibility, and even propose funding – almost Shark Tank-esque.

This assignment would lead her to map out a proposal for an organic agriculture development coupled with agri-tourism, which enabled her to angle architecture into the picture.

Gearing up along with her husband Archt. Suneth Perera and their little son in tow, Diniti proceeded to slowly execute her proposal on family owned land located within inland Tangalle in the village of Viharandeniya – where they subsequently named their own land Eranduyaaya.

They began to research viable crops suitable for the region and ROIs, and settled on growing coconut. This decision was strategic – coconut is a long-term cultivation, sometimes requiring between 6-10 years for full growth. The duo began with a variety that could be harvested in years’ time – starting off in late 2018. This level of crop management meant the family could balance the frequency of their travels to and from the farm, with the expressway cutting their travel time down to less than two hours.

They began growing coconut within 3.5 acres of the total six acres available and Diniti reiterates the importance of the MBA she earned, which enabled her to plan and strategise Phase 1 of the development with a sharpened and practical view.

The land yielded a very limited supply of water, given it’s location in the semi-arid zone of the Hambantota district. This pushed them to source a tube well, from which they rigged an irrigation system that provided an individual supply of water to each coconut plant. This proved to be a stopgap to a more significant lack of water, leading the duo to turn a quarter acre into a water hole as a sustainable measure for the long run.

Diniti also looked into the aspect of inter-cropping within the first five years – the practice of growing other crops in the space between coconut trees to maximise land use and revenue generation. The additional income would allow them to reduce the burden of juggling expenses in cultivation management via an economically sustainable approach. They started growing crops of guava, passion fruit and turmeric, with separate areas allocated for mango and banana. The lower levels held kurakkan and green gram.

Successful yields meant that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the family was able to begin harvesting and selling the organic produce to cater to incredible demand. There are requests for produce even today.

Wijeratne expresses that until then, she had not known the finer workings behind strategic business management. For example, she says, the ‘first’ in a place or region usually sets the standard and builds on the success of it. As such, she is proud to state that their organic crop farming and methods were firsts in the village and nearby regions.

Predictably, the family experienced scorn and doubt from the neighbouring villagers but Diniti is happy to report that the local mindset has changed drastically – with the villagers now taking cues from Eranduyaaya’s innovative methods and the parties now developing a mutually beneficial relationship with each other.

She claims that a turning point was the villagers observing her, Suneth and their son getting into the dirt and nitty gritty, and creating an environment of equality and sincere labour.

However, she confesses to slight lapses in prudent thinking – the family overlooked building accommodation within the land and thereby had to spend unnecessarily on hotels each time they visited.

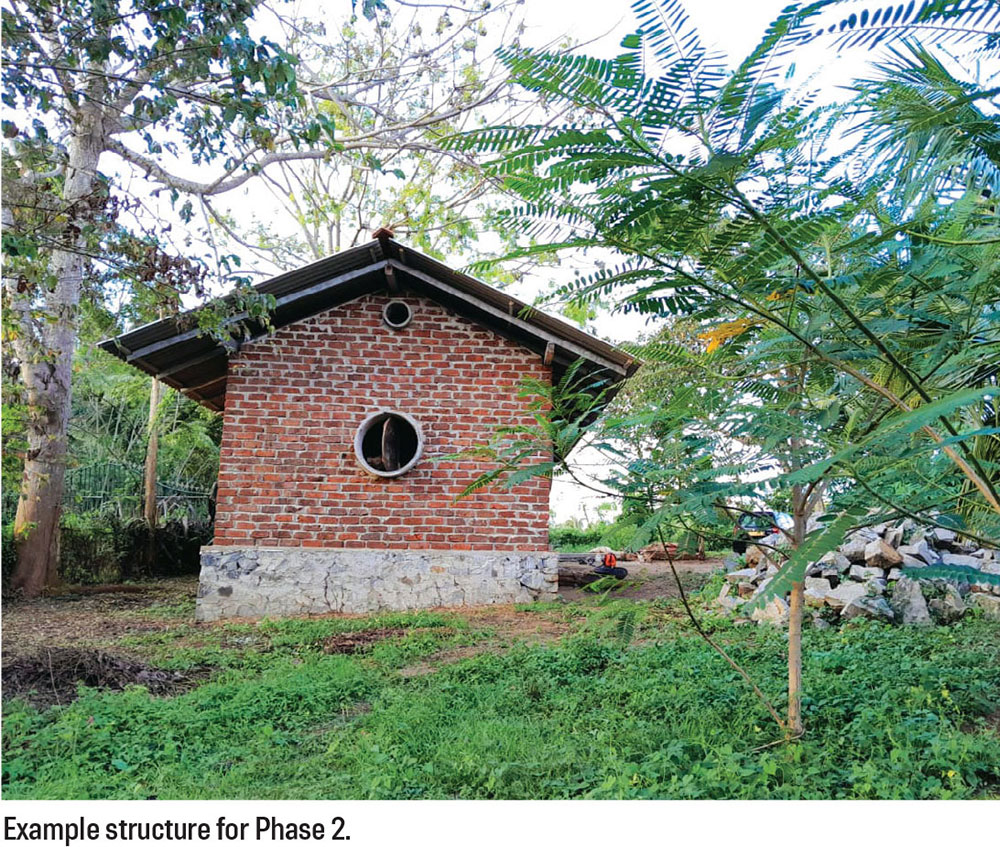

Learning from this, the little clan proceeded to build their own rustic accommodation, economically using scrap material and resources found within the land: big bricks and timber, innovatively used Hume pipes as window openings and overturned kiri hatti or clay curd pots as paving.

Diniti hopes that Phase 2 will follow the same ethos in the agri-tourism scope, with future plans for five units containing a two bedroom composition and providing a unique experience for tourists. Wijeratne’s market analysis shows that there is high demand for green tourism – especially those rooted in organic culture and agricultural experiences. Until now, Phase 2 had been severely affected by the pandemic, Easter bombings, fuel crisis and economic downturn.

When asked how she expanded public awareness about Eranduyaaya, Diniti affirms that they applied and gained Good Market certification, allowing them to sell under the organic label and push the brand further. The project has also been submitted for grant funding under the Sri Lanka Organic certification scheme by the Control Union for which they received their assessed certification.

She reiterates that Good Market certification comes with a strong social following and platform, thus poetically allowing for an organic follower base of people who are truly appreciative of natural crop growth.

In terms of branding, the logo displays a porcupine, which serves as a tribute and intention; where Diniti recounted how a family of porcupines were killed by villagers leading her to warning all who work at the farm to protect these animals. It is a memory and incident she regrets for not being able to avoid.

Finally, Diniti stresses the importance of this movement for future generations. By involving her own son in the process and place, she feels that as a city-bred child, he has now developed a keen interest in this while also being exposed to a stratum of society not typically experienced by his generation, enabling him to witness the real life struggles and existence outside of metropolitan views.

Would Diniti recommend an MBA course to all architects? “It depends,” she says. Personally, she feels that her MBA enabled her to move a few steps forward as an architect, building confidence in this formulation, and helping her strategise real-time practical and innovative methods in her approach to the profession as well as life.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Archt. Suneth Perera