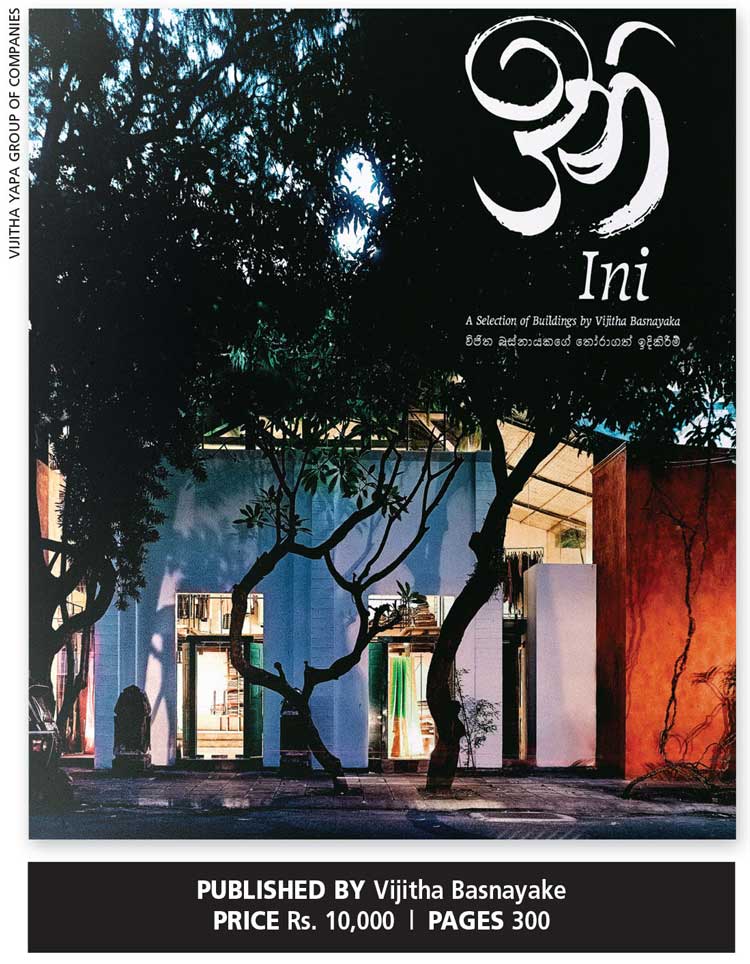

The title of this  book is intriguing. Architect Vijitha Basnayake says that ‘ini’ in Sinhala refers to poles of various kinds such as bamboo shafts, rods, galvanised iron, coconut battens and so on, which are used as scaffolds in the construction of buildings.

book is intriguing. Architect Vijitha Basnayake says that ‘ini’ in Sinhala refers to poles of various kinds such as bamboo shafts, rods, galvanised iron, coconut battens and so on, which are used as scaffolds in the construction of buildings.

“Even though these scaffolds disappear as the building reaches completion, their function, intervention and usage determine the nature, behaviour and performance of the final product. To that end, the building is as much about the process as it is about the final product. A building process evolves, drifts and nurtures through various intellectual meditations, cultural circumstances and social interventions,” he explains.

Basnayake may not be as well known as the late Deshamanya Geoffrey Bawa but he has earned himself a niche due to the way he creates buildings – especially houses – where occupants can live in comfort.

His personality makes the structures very different and offers a unique perspective of what a creative artistic life is all about.

The late architect C. J. De Saram – who admired Basnayake’s work – described him as one who has demonstrated rebellion, creativity and debate. He said that it indicated a comprehensive cohesion of design, which provided windows to one’s mind and access to that elusive inward eye from which all insight stems.

De Saram observed that the author was “a self-effacing architect” who worked with quiet detachment; and added that he didn’t design by proxy and inevitably demanded personal involvement at every stage of design.

He also noted that in the great Eastern tradition, the work of a creative artiste bore the stamp of anonymity. De Saram explained that the kings of Sri Lanka rewarded artificers handsomely for their ecclesiastical work so that any merit for excellence would be bestowed exclusively on the royal personage rather than anyone else.

Basnayake doesn’t do anything for publicity and the fact that it’s difficult to even find his name on the cover shows the depth of this innovative man.

So why did he write this book?

It may be due to De Saram’s insistence that the process of design intimated by his work is relevant not only to a favoured few but also a much wider audience.

Ini has many photographs but unlike several publications that are available in bookshops, the visuals are a combination of colour, and black and white. Every aspect of the building process is significant since they are considered very thoughtfully.

A photograph of some baas-unnaehes (foremen) working on the construction of a roof indicates the importance that Basnayake places on basic creations and those who build the architectural marvels he designed.

While browsing through the pages of this book, one sees that the intellectual and creative process of Basnayake’s architecture is passionately rooted in the pragmatic traditions and approaches of the local construction industry, environmental features of the regional landscape and tactile qualities of the spaces he creates.

A unique feature of this book is that the author has also given descriptions in Sinhala. Rather than simply creating a collection of pictures, the details he presents to readers make the images come alive.

These descriptions are valuable as they provide insights into the mind of the architect and the creative processes that turn bare land into innovative domains. Unfortunately, the quality of the pictures is poor and his painstaking work isn’t captured in detail.

Ini also contains information on innovative architecture in Sri Lanka. One building showcased in the book is the Karagahagedara Ambalama in Narammala, which is a resting-place for weary travellers.

It balances on top of four boulders that sit on an undulating rocky outcrop and is aptly described as one of the finest monuments of Sri Lankan architecture. Innovations such as these abound in this book.

Strong environmental and ecological concerns, as well as physical landscapes, are all important when appreciating and recognising nature’s right to remain intact despite growing construction needs.

Basnayake’s work is special because he has learned from a past that’s steeped in tradition and is building in the present for the future.

The use of locally available wood – including materials such as discarded railway sleepers in some of the buildings he created – provides a unique and rustic look.

Basnayake observes: “Some speak about an ad hoc quality in our work. I think it is an outcome of this way of informal building… We don’t see construction as a rigidly planned activity. It is a journey of constant transformation and evolvement.”