SCREENS AND SPACES

SPOTLIGHT

THE PHENOMENON OF THE CYBER CAFE by Archt. Shahdia Jamaldeen

The phenomenon that is the internet has made its presence known in different capacities, influencing and shaping generations by expanding access to information, communication, learning and economic opportunities. At the same time, it has introduced new and unexplored challenges such as cyber bullying, the circulation of explicit material and cybercrime. Each generation has developed its own identity and resonance with the internet – both in its methods of usage and in how it has shaped socio-cultural landmarks. So much so that the imminent threat of Y2K or the ‘millennium bug’ – a potential global cyber and societal crash predicted due to a programming error culminating at the turn of the millennium – gripped the world. It created an entire generational movement in cultural trends, fashion aesthetics, media programming and retro futuristic or synthetic design.

Baby boomers (born in the years 1955 to 1964) encountered the internet later in life and adopted a cautious, even wary stance towards it. Yet they openly embraced it as an essential tool for communication, especially in maintaining family relationships. Generation X (born between 1965 and 1980) integrated the digital age more deeply into both their personal and professional lives. They were among the early users of social media platforms such as Facebook, MSN and Yahoo!, while also transitioning communications heavily into online portals such as e-mail and chat. Digital innovation was then spearheaded by the millennials (born during 1981 to 1996), a key cohort that experienced both analogue systems and the digitisation of everyday functions and software. Their coming of age in cyberspace helped develop social media, online trade and shopping as well as automated integration systems. And finally, the digital natives of today – Gen Z (the generation spanning 1997 to 2012) – were born, raised and taught in a world where the internet was already a solidified presence. It is firmly integrated into their everyday lives, to the extent of digital media affecting and evolving their thinking, behaviour and linguistic patterns.

Architecture has not been immune to the evolving notions of technological advancements and its practices. As with all notable cultural and social movements, the built space has continued to reflect these advancements through new typologies and communal environments. Among the many theories of architecture that have evolved and retrofitted their principles accordingly, urbanist and post-modern political geographer Edward Soja’s Theory of third space – derived from Henri Lefebvre’s Lived Spaces, Michel Foucalt’s Heterotopias and BELL HOOKS’ positionings – offers an interesting overlay to examine.

Soja stated that macro and micro level urban spatial comprehension went beyond simply analysing physical attributes and also included examining social, political and cultural aspects, overlaid with the study of the community’s perceived reality, mental representations and lived experiences. This holistic overview of spatial study was structured into first, second and third space paradigms, with this article concentrating on the concept of third space. Soja maintained that the notion of third space was a highly dynamic and perpetual state of space, encompassing perceptions of both physical and mental spheres – essentially, lived space.

The ever changing quality of third space means that its application and typology invite users to develop and experience ideas, events, gatherings and transformative experiences – retaining a multitude of potential. All these aspects are brought to life by the physical gathering of like-minded or similarly placed individuals who consciously or unconsciously bring together their memories, experiences, imaginations and influences.

As such, Soja outlined certain characteristics of third space. It is a geographically located social space that embodies historicity, sociality and spatiality as transdisciplinary – what he called The Triple Dialectic, encompassing experience, social interaction and social space. Each place can be seen clearly and from multiple perspectives, yet there is also a hidden dimension that is conjectured, full of deceptions and allusions – a space shared by all but never fully seen or understood, an ‘unimaginable universe.’

It is a space of complete radical openness, free from the conflicts of race, gender, class, sexuality, age, country, religion, nature, empire and colonialism.

In simpler terms, third space refers to highly social gathering spaces and urban environments that are distinctly separate from primary typologies such as the home, office or school. These include publicly accessible spaces including community centres, squares, halls, plazas, parks, restaurants, cafes and libraries – all which foster and sustain functions that allow users to remain for extended periods of time effectively and efficiently. They also provide amenities such as ergonomic seating, balanced temperature control and of course, internet access. These intermediate spaces are often open to people from all walks of life regardless of social status, class or ethnicity and are designed to cultivate a sense of belonging and community wellbeing.

Similarly, spaces that emerged from the need for cyber related activities and social movements took shape in the form of VR areas, coworking hubs, gaming centres, hybrid public venues, fulfilment spaces and the titular internet or cybercafes. While philosophers and theorists such as Habermas and Laurier emphasised that the physical public spheres were imperative for primary social engagement, rational interaction and healthy dialogue, the rise of technology has dramatically changed this narrative. Cybercafes and gaming centres turned communication and idea exchange on its head, creating a new kind of third space – one located within the endless and infinite expanse of the internet. Much like a set of Matryoshka dolls, the confined space of a cybercafe held within it portals that led to a boundless digital realm, held together by twittering, flashing modems – portals nestled within one another.

Cybercafes were conceived as part of an initiative to bridge the digital divide by creating cost-effective, customised spaces that helped communities familiarise themselves with the internet through a blend of physical, social and virtual elements. In Sri Lanka, the first cybercafes aimed to provide web access in a relaxed environment, often including refreshments and an informal setting.

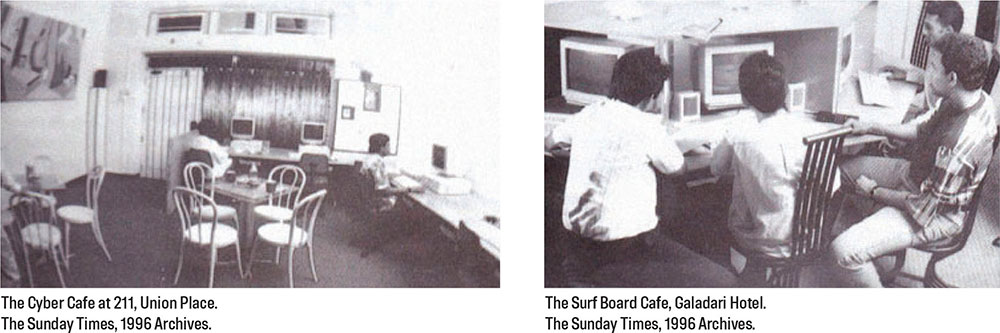

In 1996, Colombo saw the opening of two pioneering spaces; The Cyber Cafe at 211, Union Place and The Surf Board at the Galadari Hotel. The Cyber Cafe at Union Place was conceived by Ratten Abdulhussein – a bold move reinforced by her education in computer science gained in Britain, where this typology had been introduced two years earlier, in 1994. Abdulhussein saw the need to capitalise on keeping up with the times, along with Sri Lanka’s own budding interest in the internet, and went on to establish one of the first functioning cybercafes in partnership with two others. Since its opening in March 1996, the cafe saw a surge of more than 200 visitors – all curious to explore the online realm.

The Surf Board was formalised through a corporate venture between the Galadari Hotel and Lanka Internet Services and was headed by Vaseeharan Nesiah who stated, “The concept of cyber is not something easily understood in Sri Lanka, so we decided to call ourselves Surf Board instead, because using the internet is known as surfing.”

The novelty of these functioning cyber portals held both fascination and function for a growing clientele that began to see the merit in cross boundary resource accessibility and modern communication methods. From a seat in Colombo, one could access university libraries in Oxford and Cambridge, browse research material, establish business contacts and stay in touch with family and friends abroad through e-mail. Both cafes advertised their spaces as conducive environments for leisure, gaming, networking and business – all for a nominal hourly rate.

The spatial layouts of both cafes were modelled on the standard design of eateries, with the computers set along the walls of the compact setting. At Surf Board, the layout was more communal, with the machines clustered together to allow for groups of web surfers to gather while engaging with the internet. The requirement for privacy at this stage was far less compared to the greater need for undisturbed usage that would emerge later on – also signalling a dangerous rise and creativity in cybercrime and hacking.

In terms of the spatial design of 211, Union Place, the interior “was like the other cybercafes around the world – a cross between a cafe and a computer room. The carpets are a beautiful royal blue and a vivid painting by Sri Lankan painter Sita Joseph de Saram dominates one wall. There are computers set up all around the room against the walls and in one corner, you get a bar of Swedish pine which has a coffee machine and soft drinks machine.”

Internet cafe typologies also helped reinforce the early concept of ergonomics within Sri Lankan design culture. David Brettell, a computer teacher at Overseas School of Colombo in 1996 claimed, “Cybercafes are really a good thing because they allow people who can’t afford their own computer or internet connection to surf the internet. I just hope that these are places with a relaxing and friendly atmosphere and good, comfy chairs and tables. You know, it’s very difficult to work well at a computer when you’ve got to sit on straight backed chairs or at tables that are too high!”

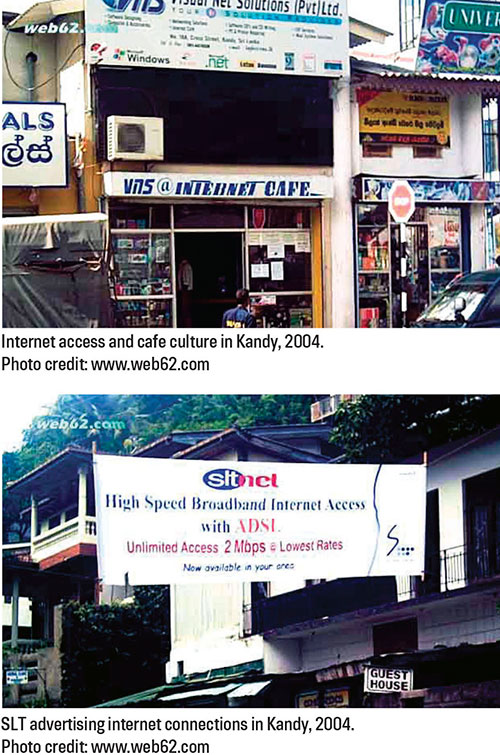

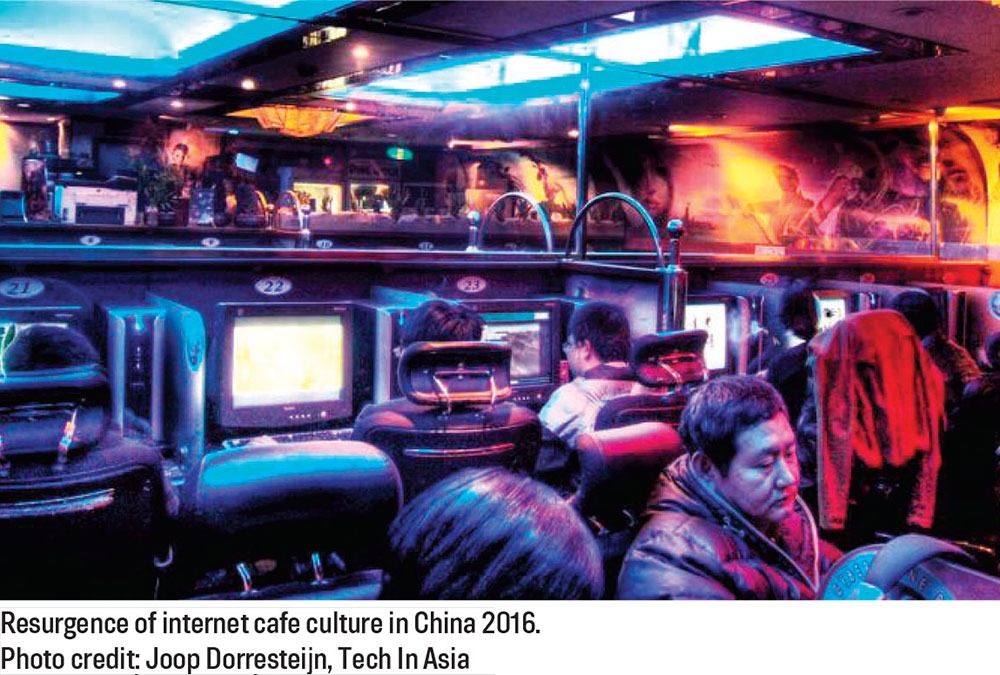

By the late 90s, cybercafes were mushrooming rapidly, parallel to the burgeoning internet culture and techno-optimism, and by 2002 China was home to as many as 200,000 licensed cafes. With the alarmingly increased and often unregulated access, aspects of surveillance – both in physical and online spaces – began to emerge as negative consequences. As a result, internet cafes started to host fairly nefarious activities, taking advantage of the anonymity and open public access they provided. With the development of 3G technology and the easy mobility of the smart phone, 2010 saw a steady decline in internet cafe usage and development.

To stay relevant while tapping into other avenues of cyberculture, most internet cafes began converting their major functions to host online and software based gaming. Similar to the spatial nature and design orientation of betting centres, the newly converted gaming cafes sought to create dimly lit, neon laced, 24-hour environments within shuttered and cloistered spaces. These designs physically and mentally enclosed users, reducing awareness of the external world through continuous interaction with the addictive world of online gaming, with some users spending hours and even days within these morphed spaces.

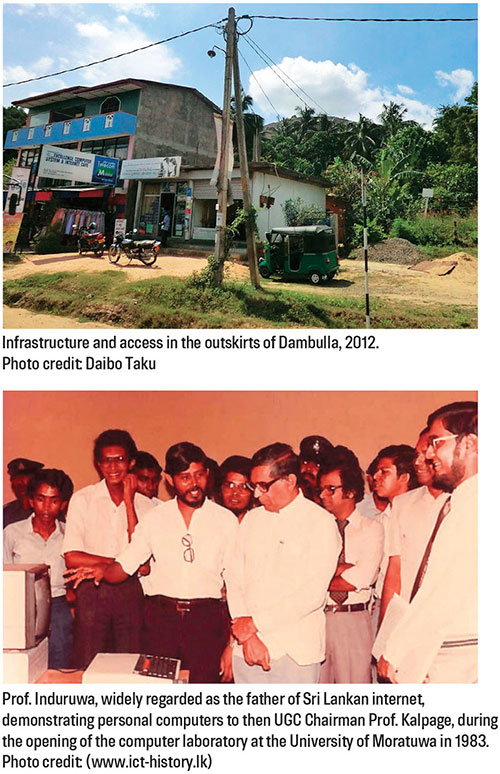

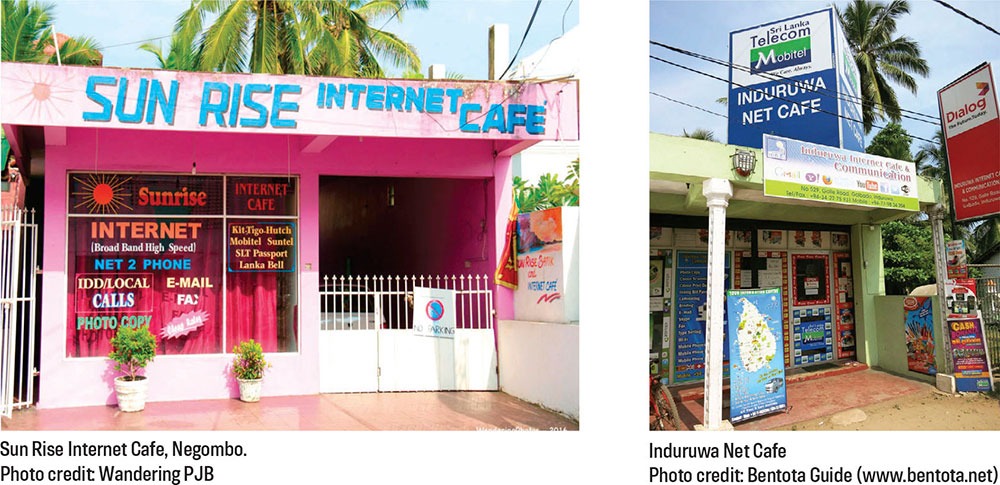

By 2013, cybercafes had largely become irrelevant, with COVID-19 and multiple lockdowns swinging the final blow. More than the loss of a space for cyber access, the disappearance of a node for communal sharing, gathering and exploration truly impacted communities. Gaming hubs such as Excel World (formerly known as Millennium Park) saw rapidly declining footfall. Meanwhile, a few small-scale internet cafes still remain, serving as the only sources of online access in parts beyond Colombo and urban districts.

The Cyber Cafe highlighted the importance of third spaces – spaces deeply connected to growing technological advancements and socio-cultural evolutions. While Sri Lanka tapped into the cyberculture game early on, there is still a lack in infrastructure and specific techno-gathering spaces that could help a growing sector of students, professionals, ability compromised groups and self-employed individuals progress healthily. This became particularly evident during the pandemic, when students in remote areas were unable to access stable connections, while their urban counterparts exhibited compromised interpersonal and social skills due to their reliance on interaction via the internet.

While our lives are now largely represented through our online avatars, we can begin to appreciate the vital role that internet cafes once played in our growth. It is truly incredible to have begun our cyber lives at 64kb speeds and now be indifferent to downloading gigabytes worth of content onto terabyte sized storage. It is important that we do not forget the humble beginnings of the world wide web in Sri Lanka, while continuing to recognise the value of physical interactions and relationships, amplified through thoughtfully structured third spaces. It only strengthens the conviction that architecture will remain as relevant and indispensable as a strong internet connection.

As Abdulhussein declared nearly three decades ago, “With the advent of the Cyber Cafe, we hope to encourage more and more people to get online and enjoy the benefits of the communication age, while not sacrificing the help and sociability that come with the human touch.”

REFERENCES

Y2K. (n.d.). National Museum of American History. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object-groups/y2k#:~:text=The%20term%20Year%202000%20bug,elevators%20which%20used%20computer%20chips

Generational differences in the digital world: How the internet shapes lives across different age groups – messendly. (n.d.). https://messendly.com/blog/blog2

Khant, D. K. (2023). Third Spaces in Architecture: Edward Soja. Rethinking the Future. Retrieved September 20, 2025, from https://www.rethinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a10494-third-spaces-in-architecture-edward-soja/

Xing, Z., Zhao, R. & Guo, W. From traditional to digital contexts: new characteristics of the public’s spatial perception of urban streets in the age of technology. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1486 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04015-z

Tecgasoft-Content. (1996, May 30). A growing interest in the internet! Business Today. https://businesstoday.lk/a-growing-interest-in-the-internet/

Aziz, A. A., & Farook, F. F. (1996, March 10). A quick byte in cyberspace. The Sunday Times Plus. https://www.sundaytimes.lk/960310/plus/plusm.html

Zelenko, M. (2025b, June 14). The world’s last internet cafes. Rest of World. https://restofworld.org/2023/internet-cafes/

PHOTOGRAPHY

Wandering PJB

K. K. Wasantha

Markus Matzel/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Jie Zhao/Corbis via Getty Images

Daibo Taku

The Sunday Times, 1996 Archives

Wandering PJB (https://www.flickr.com/photos/101569217@N06/52297363755/in/photostream/)

Induruwa Internet Cafe www.bentota.nethttps://bentota.net/internet-cafe-und-sim-karten-induruwa-103/

Feisal Omar/Reuters

Joop Dorresteijn | Tech In Asia https://cdn.techinasia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/internet-cafe-750×433.jpg

(https://www.web62.com/_srilanka1/pix/internet-cafes.jpg)

(https://www.web62.com/_srilanka1/pix/sri-lanka-internet.jpg)

Daibo Taku (https://web.archive.org/web/20161020161811/http://www.panoramio.com/photo/65683926)

(https://arteculate.asia/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Prof.-Induruwa-Father-of-Sri-Lankan-Internet-v2-1-700×480-1.png

https://www.ict-history.lk/en/abhaya-induruwa-prof/ | Ananda College

Pulse.lk

(https://pulse.lk/pulse2022/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Untitled-design-19.png)

(https://encryptedtbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcSSBxPJzuqcvPoTG6F4iYCMmqfYQHKY4zyNrLErdlrsQNxRiZrMNTnFmjgkTm-PipVx5bM&usqp=CAU)