TRUMPONOMICS 101

TRUMP AND TRADE POLICY PIVOT

Samantha Amerasinghe assesses the likely impact of US trade policy actions

Trade policy was a key feature of Donald Trump’s campaign platform, and recent action and rhetoric suggest that it remains his top priority. As one of his first policy actions, President Trump cancelled US participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiated by his predecessor, the deep trade integration deal the United States had signed but not ratified.

It remains to be seen whether or not the withdrawal will help American workers but what Trump’s decision has created is much uncertainty.

The US president also announced his intention to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the US-Canada-Mexico arrangement that’s been in force since 1994.

But no one yet knows what this all means.

He has threatened to pull out of NAFTA if the US does not get what it wants. By contributing to the development of cross-border supply chains, NAFTA reduced costs, increased productivity and improved US competitiveness. One study highlights that in the seven years following NAFTA’s passage, nearly 17 million jobs were created and the unemployment rate fell from 6.9 percent to four percent.

Despite this, some argue that the surge in imports led to the loss of up to 600,000 jobs in the US over two decades. Critics point to these numbers to blame trade and agreements like NAFTA for the decline in US manufacturing jobs. The automobile industry lost about 350,000 jobs since 1994 – that’s a third of the industry.

US trade with Canada and Mexico now amounts to more than US$ 1 trillion annually and represented 30 percent of its trade with the world in 2016, supporting about 41 million jobs.

For companies, the US pulling out of NAFTA would have dire consequences: they would have to unwind long-term investments and do without access to cheap labour in Mexico, which in turn reduces their ability to compete against China and other low-cost producers.

The threat of imposing a 35 percent ‘border tax’ on businesses that operate factories in Mexico rather than the US could be hard to deliver, given that it would violate the terms of NAFTA and the US’ commitments as a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Delivering on the threat could also be politically challenging for Trump as many Republicans in Congress have already made it clear they would oppose new tariffs.

Trump has said the renegotiation of NAFTA is likely to be an 18-month process. But he has threatened to withdraw by using his executive powers, if the deal does not result in ‘fair trade’ in the best interests of American workers.

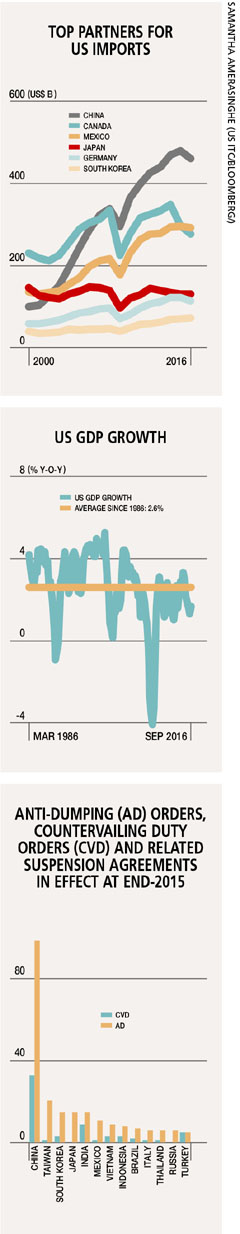

Interestingly, Mexico and Canada have had limited trade friction with the US in recent years especially compared to Asian trade partners such as China, which tops the list of current anti-dumping duty orders in place – 99 orders at the end of 2015 compared with 11 for Mexico and two for Canada.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, the annual meeting of global political and economic leaders, China’s President Xi Jinping positioned himself as an unfaltering defender of free trade and globalisation.

This is in stark contrast to Trump’s protectionist and anti-globalisation stance. Trump has positioned himself as a defender of the ‘forgotten people,’ pledging to put America’s interests first. And he has made it clear that a more assertive trade policy is a priority.

Does this suggest that China is going to play a more active role in global politics? And is China the new champion of free trade?

Following the US’ withdrawal from the TPP, there’s widespread concern among TPP partners that America is abandoning the former administration’s ‘pivot to Asia’ strategy. While the other 11 TPP members could create a parallel agreement and move forward without the United States, economic benefits would be substantially reduced without US participation.

Excluded from the TPP, China is the only country that may benefit from the US withdrawal. It has been forging ahead to finalise its own regional trade agreement – the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

Now that the TPP is virtually dead and buried, Asia is seeking to shape new trade deals. Attention is turning to the RCEP, which covers 16 nations including Australia, New Zealand and India.

Many countries are open to China joining the TPP but some may prefer to focus on the RCEP as an alternative regional trade liberalisation initiative.

As the US pulls back from multilateral trade deals under Trump, it will no longer be at the centre of efforts to liberalise trade. This will leave a void that is unlikely to be filled even by China, which is likely to remain more active regionally than globally by using limited political capital to address global problems that do not affect its own national interests.

Trump has outlined a bold plan to get the economy back on track by creating 25 million new jobs in the next decade and raising GDP growth to four percent by 2018/19. This looks somewhat ambitious given Trump’s protectionist stance – growth has averaged 2.6 percent since 1986 and 2.1 percent from when the recovery began in mid-2009.