TRADE DECOUPLING

COVID-19 AND SUPPLY CHAINS

Samantha Amerasinghe sheds light on the consequences of trade decoupling

The coronavirus pandemic poses the largest threat to global growth since the 2007/08 financial crisis. Suspended production activities and disruption to supply chains will be among the most significant factors, leading to a major drag on global economic growth as 2020 unfolds.

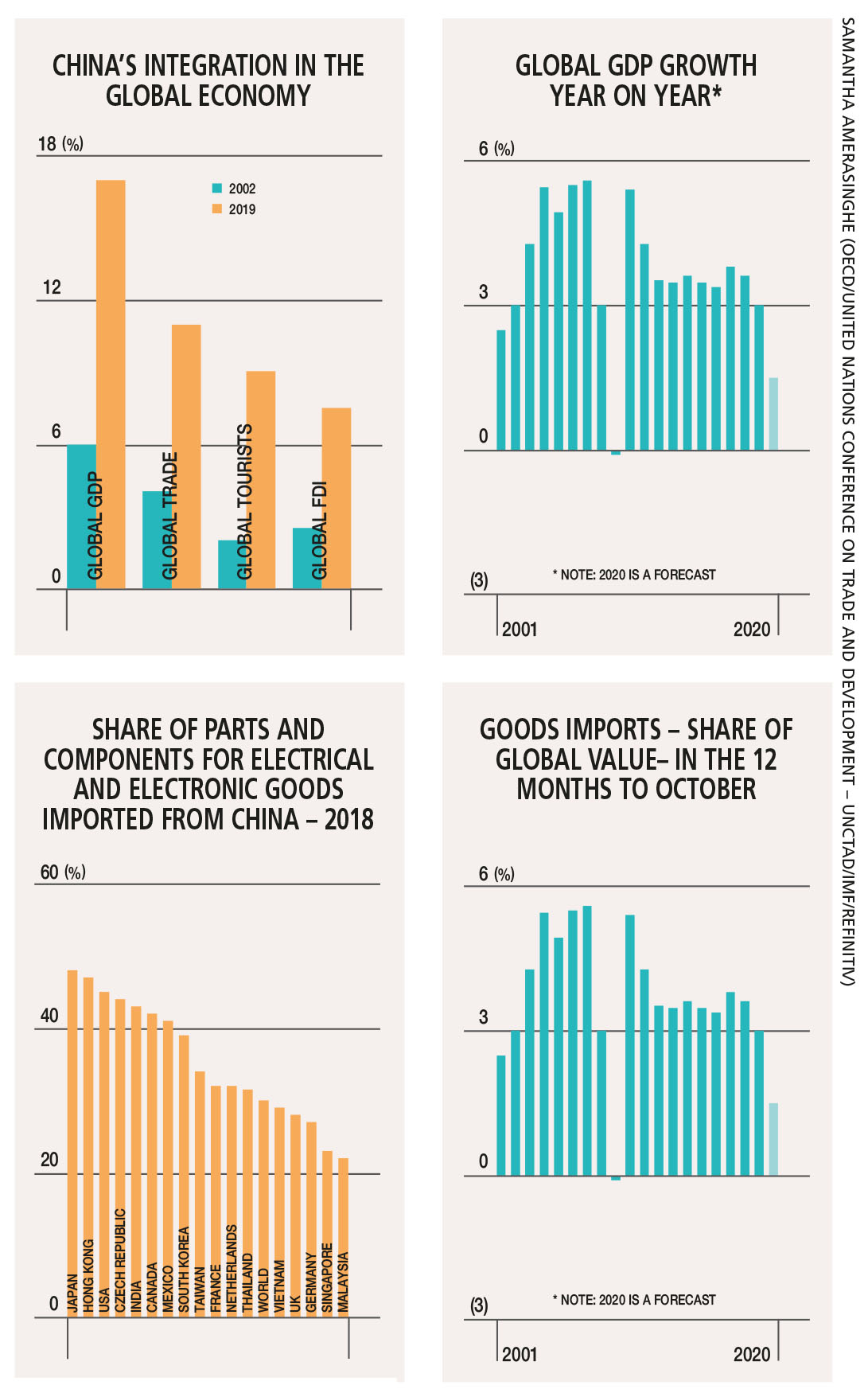

Indeed, the global economy has become substantially more interconnected, and China plays a far greater role in worldwide output, trade, tourism and commodity markets. Economic spillovers to other countries will be inevitable even if the pandemic itself is short-lived.

COVID-19 has prompted experts to claim that it will accelerate the ‘decoupling’ of China and the US. Some countries in the West have called for international trade decoupling given the vulnerabilities of globalisation that have resurfaced amid the coronavirus outbreak.

So what are the consequences of decoupling, and its negative and positive impacts on supply chains? And will this pandemic only warrant short-term decoupling?

The OECD has predicted that an intensive coronavirus outbreak could weaken global growth to 1.5 percent this year. Even that estimate seems too optimistic given the nationwide lockdowns witnessed around the world. It would be wishful thinking to hope that countries will rebound speedily from this pandemic.

OECD economists estimate that if the unprecedented containment policies implemented by governments are in place for three months, annual output would drop by six percent in developed economies. For the US – where the economy was projected to grow by two percent before the virus spread across the world – the implication is that output will decline by four percent in 2020.

Meanwhile, the World Bank forecasts that China’s economic growth would fall to 2.3 percent this year (from 6.1% in 2019) in the more optimistic of its two scenarios but drop to 0.1 percent if lockdowns continue into next year.

The risk of the world’s two major superpowers decoupling initially surfaced as trade tensions heated up in 2018. It seems that COVID-19 – rather than a trade war – has expedited some of that decoupling as countries consider the long-term consequences for supply chains.

A so-called ‘partial’ deal signed on 15 January, the phase one trade agreement between China and the US, signalled a truce in the trade war. Although US officials view this as a first step in attempting to integrate two very different systems, others are sceptical – they expect decoupling between the two powers to continue.

The partial trade deal includes a commitment by China to purchase at least US$ 200 billion worth of American goods before the end of 2021. An escalation of tariffs by both parties has ended and the promise of commencing phase two negotiations (to be concluded after the US presidential election in November) boded well for relative peace on the trade war front.

However, the effect of the corona virus may have provided China and the US an opportunity to renege on the agreement. If commitments from either side aren’t met anytime soon, COVID-19 will take the blame for delays in implementation.

virus may have provided China and the US an opportunity to renege on the agreement. If commitments from either side aren’t met anytime soon, COVID-19 will take the blame for delays in implementation.

Decoupling of the world economy has negative impacts such as higher costs especially on global hi-tech supply chains. But it’s important to recognise that decoupling also has potential benefits.

As witnessed with the coronavirus outbreak, supply chains can be potentially disrupted not only by trade disputes and geopolitical tensions, but also natural disasters and epidemics. Decoupling provides the conditions under which second sources for any link in a supply chain may be developed successfully.

Many US companies are shifting their supply chains to other Asian countries. This growing ‘decoupling’ or separation extends beyond traditional goods and services, to advanced technologies such as AI, robotics and genomics. China’s goal – in the face of US export bans on major technology inputs – is to create its own internal tech supply chain. So we’ll witness decoupling in telecommunications, internet and ICT services, and 5G systems. The best response from the US to China’s innovation agenda is to strengthen its own onshore capabilities.

The decoupling of global hi-tech supply chains due to US-China trade tensions will be costly and perhaps unavoidable; but in the long-term, it would be better for consumers globally to have two suppliers of similar goods and services competing with each other.

COVID-19 has underscored to the US – and China’s trade and investment partners – the value of diversification away from the PRC. However, the economic impact of COVID-19 though severe, may only warrant short-term decoupling.

Global supply chains of many companies including US businesses (e.g. automakers and tech firms) are heavily dependent on an array of products that originate in China. Companies that have relocated the assembly of products such as smartphones remain reliant on components manufactured in China.

If disruptions persist beyond a few months, retailers and consumers will be hit by delays and a slump in factory orders.

During this economic downturn, companies will seek short-term replaceable market and manufacturing locations outside China. But given its sheer market size and deep integration with the global economy (China contributed 11% of global trade last year), leaving China will be a bad idea if the pandemic ends in the months ahead.

COVID-19 should not be an excuse to justify the ‘permanent decoupling’ of China and the US.

Decoupling of the world economy has negative impacts such as higher costs especially on global hi-tech supply chains

Leave a comment