COVER STORY

THE WORLD OF WORK

Evolving labour dynamics

Simrin Singh discusses the imperatives for working people in Sri Lanka and beyond in an evolving labour market

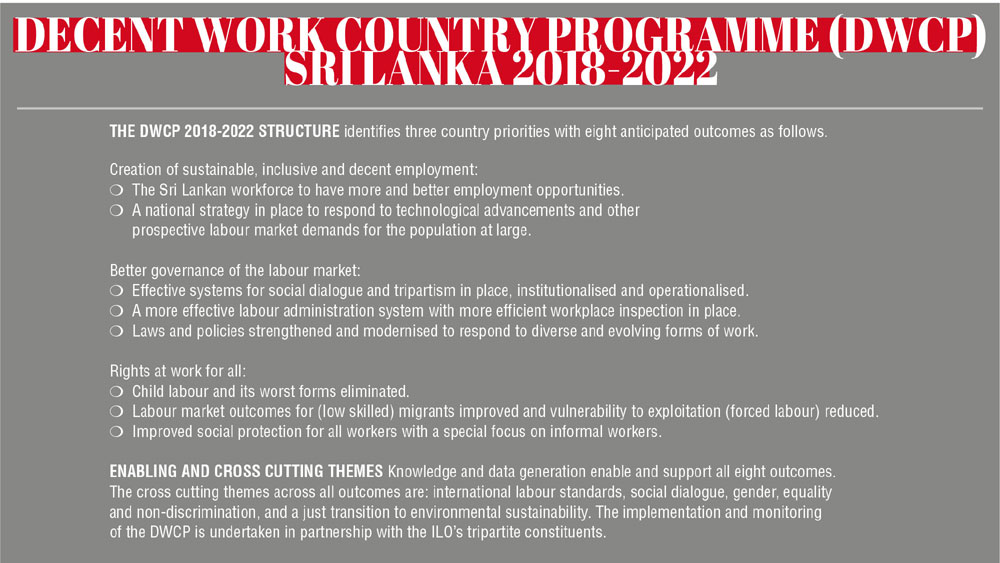

Setting labour standards, developing policies, and devising programmes to promote decent work for all women and men fall within the ambit of the ILO – a tripartite UN agency that has brought governments, employers and workers from over 180 member states together since as far back as 1919.

Simrin Singh officially took over as the new Country Director for the ILO Country Office for Sri Lanka and the Maldives on 1 April last year. In this exclusive interview with LMD, she highlights a number of priorities for both policy makers and business in general, with a special focus on labour and the employment landscape.

Among other core concerns with respect to the broader labour market are productivity in both the local and regional context, pay scales and their impact on productivity, labour regulations, the concept of work-life balance and what constitutes a ‘great workplace,’ as well as issues faced by the ‘working poor.’

While commending Sri Lanka’s “relatively stable macroeconomic position,” the ILO’s Country Director observes that “gaps do continue to exist in terms of adequate scope and application of the laws, particularly given the high degree of informality in the Sri Lankan labour market and changing patterns of work.”

Furthermore, education and literacy receive attention with Singh noting that “the emphasis in the modern world is not only on knowledge transfer but skills transfer as well, bringing into sharper focus the urgent need to focus on the quality of education.”

A national of the United States, Singh has been an ILO staff member since 2000. She has held various positions in different ILO offices as well as at the headquarters of the International Labour Organization in Geneva.

Her most recent post at the ILO (between 2008 and early 2017) was as a Senior Specialist on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work – she was based at the ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific in Bangkok.

– LMD

How important is it to improve productivity especially in a local and/or regional context – and what must be done to achieve this?

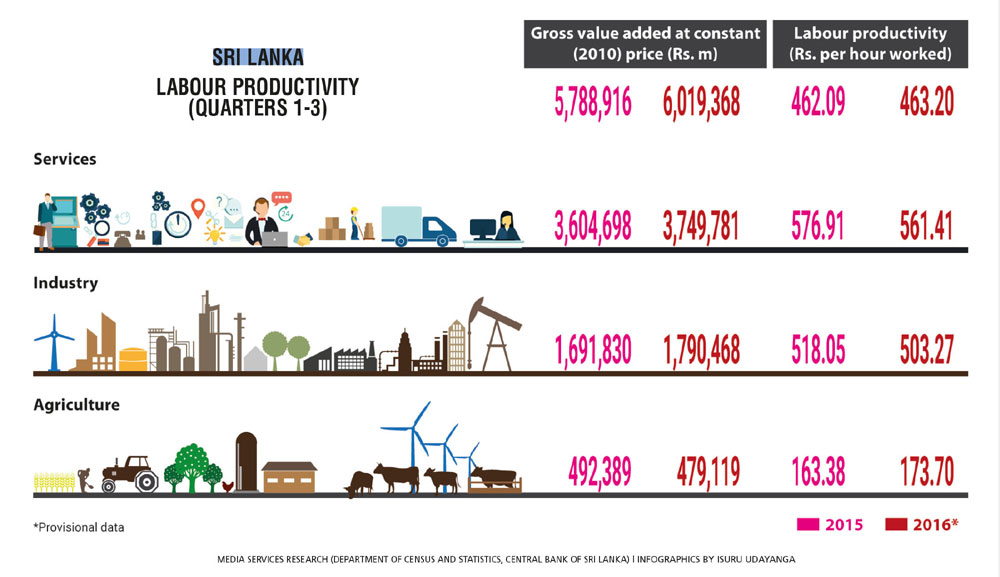

Labour productivity is an important economic indicator that is closely linked to economic growth, competitiveness and living standards within an economy. Each of these factors needs to be addressed for productivity to improve.

Sri Lanka has achieved economic growth above seven percent on average and enjoys a relatively stable macroeconomic position but household incomes or living standards have not kept pace with GDP growth. Therefore, a key objective over the medium term must be to ensure more robust income growth at the household level along with broader economic development.

Sri Lanka has achieved economic growth above seven percent on average and enjoys a relatively stable macroeconomic position but household incomes or living standards have not kept pace with GDP growth. Therefore, a key objective over the medium term must be to ensure more robust income growth at the household level along with broader economic development.

Economic growth must be broad based and not limited to a few narrow sectors that benefit only some segments of society.

For a small nation of 21 million people, achieving the country’s full economic potential and sustaining growth over the long term will depend on the ability to build a robust export led economy. This includes increasing the competitiveness of the SME sector. Linking SMEs to larger enterprises to enable greater access to markets and other spillover benefits – such as knowledge and technology transfers, and financial stability – could greatly improve productivity.

When looking at labour productivity within a local regional or global context, unequal development is likely if the centres of labour productivity growth are spatially concentrated.

This can lead to rising regional as well as other spatial (i.e. rural-urban) inequalities as large productivity gaps emerge.

Therefore, it is important to have a growth strategy in place, which is sectorally balanced and sensitive to increasing spatial inequalities. The better the spread in productivity growth, the better the distribution of its gains.

Do you believe that pay scales have a major impact on productivity?

Do you believe that pay scales have a major impact on productivity?

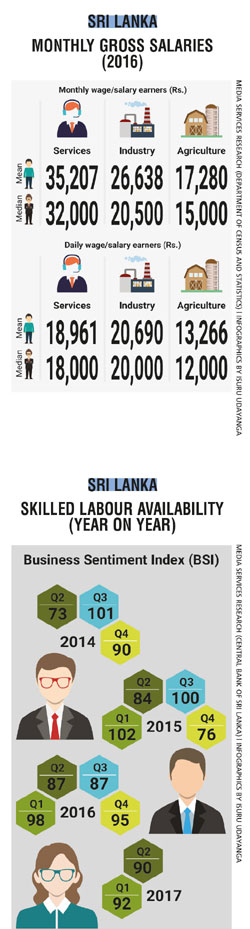

A base salary guarantee, which Sri Lanka implemented through minimum wage legislation in 2016, should serve to provide workers with security, knowing they will receive at least a minimum pay for their work time.

Nevertheless, when salaries aren’t sufficient to meet workers’ needs or are not in accordance with their level of endowments, it is likely that they will look for better options in the labour market.

This can lead to high turnover rates and low levels of commitment during the hours of work, which is likely to impact productivity. It is important to set pay scales according to the various levels of responsibility and skills that different employees have in an enterprise – and these should be adequately rewarded through a wage premium.

The 2016/17 ILO Global Wage Report finds that in medium and large European enterprises, most people (close to 80%) are paid less than the average wage of the enterprise in which they work. Thus, the average is an imperfect measure of what workers in those enterprises really earn. Zooming in on the enterprises with top average wages, we find that inequalities grow to sometimes enormous levels.

Adequate levels of pay scales can be set in an appropriate manner through dialogue between employers and workers. Collective bargaining at the workplace level is a possible way forward to establish an adequate level of wages that will induce an increase in productivity. However, the high level of informality in employment makes linking productivity with pay a difficult process.

What are your views on work-life balance as well as the ‘work hard/smart, play hard’ motto?

Work-life balance translates into happier and more invested workers; it increases labour productivity, and in turn benefits business and the economy.

The issue is not simply one of business affordability of wages but transforming the business culture to recognise that investing in work-life balance measures is profitable. It means having measures in place to make workplaces safe, hours flexible, wages decent and income security adequate. All these measures will lead to a balanced life – and a productive labour force.

Productivity declines when workers aren’t paid adequately, work gruelling hours or multiple jobs ending in sickness and missed days – and businesses have to bear the expensive burden of recruitment, constant training and retraining new workers.

Earning capacity and income levels do have an impact on the ‘play hard’ aspect of this balance, giving workers no choice but to seek secondary jobs to make ends meet.

Earning capacity and income levels do have an impact on the ‘play hard’ aspect of this balance, giving workers no choice but to seek secondary jobs to make ends meet.

In Sri Lanka, poverty and income data indicate that a fairly large proportion (11%) of the total employed population hold secondary jobs. Additionally, a number of international buyers of goods, reflecting the sentiments of today’s consumers, are clear that they value higher labour standards and the quality of products as important factors besides low costs of production. Competitive wages that can contribute to workers’ higher living standards go hand in hand with better and quality products (and services), making them more attractive to buyers.

How would you characterise education and literacy in Sri Lanka – and what are the pros and cons of free education?

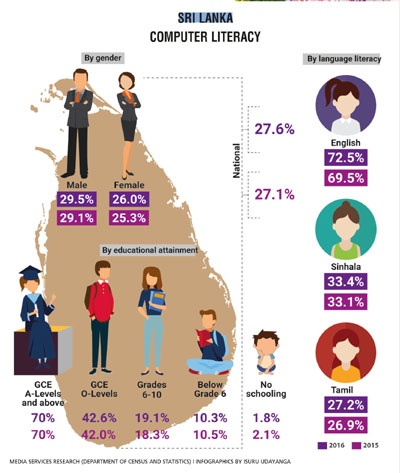

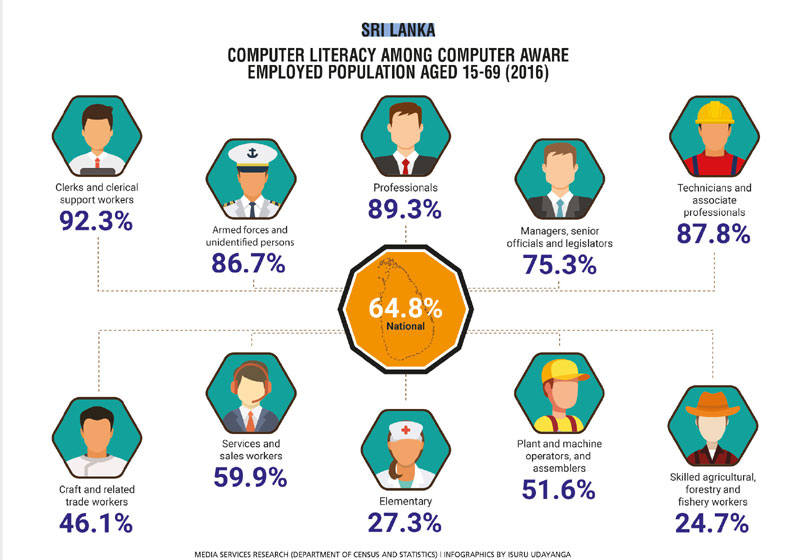

Free education has without a doubt helped Sri Lanka achieve impressive levels of literacy and educational attainment, and also contributed to high social and quality of life indices. However, the emphasis in the modern world is not only on knowledge transfer but skills transfer as well, bringing into sharper focus the urgent need to focus on the quality of education to equip graduates with the right core and technical skills to be able to integrate into the world of work.

There is overall a greater need to effectively link education systems with labour market needs.

There is overall a greater need to effectively link education systems with labour market needs.

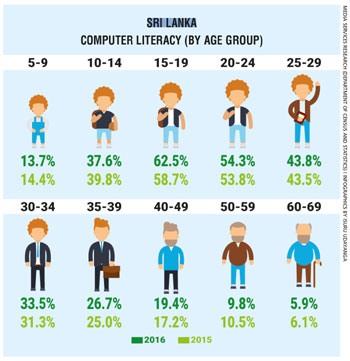

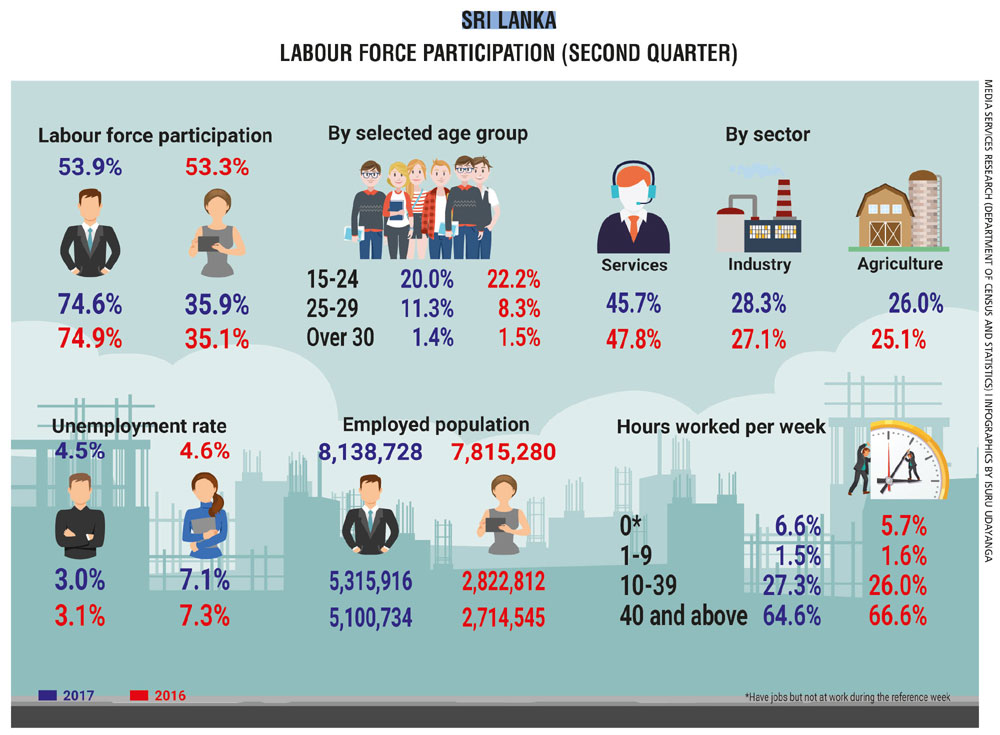

In Sri Lanka, despite impressive gains made in education and literacy, these have not fully translated into favourable youth employment outcomes. Data indicates that some of the highest unemployment rates are recorded amongst youth with higher educational attainment whilst in general, Sri Lanka’s youth are three times as unemployed as their adult counterparts.

The present global unemployment rate for youth stands at 13.1 percent (or one in eight youth). In Sri Lanka, the youth unemployment rate is even higher, standing at 18.5 percent (almost one in five youth) as of the first quarter of 2017. So there is certainly a need to skill Sri Lankan youth for today’s and tomorrow’s jobs.

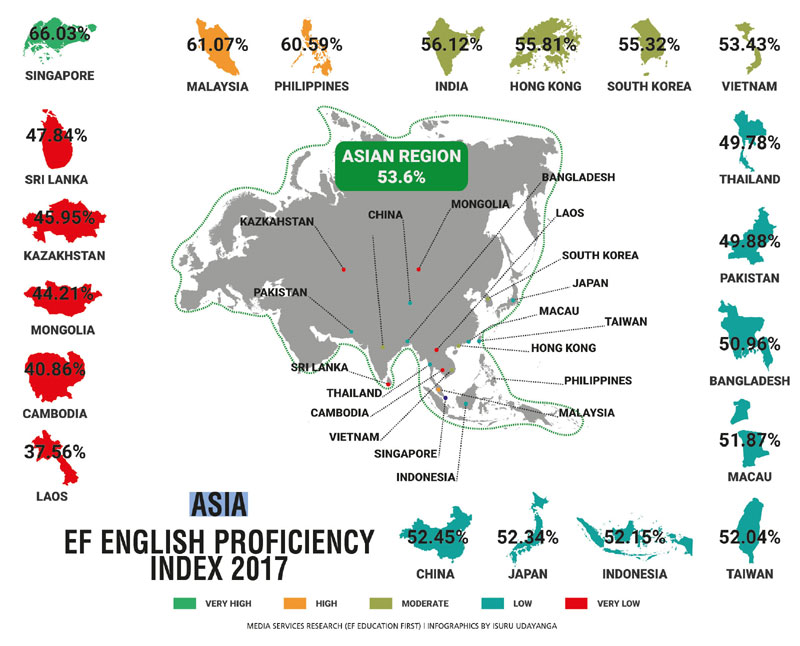

How do you view the importance of English as the universal language and where does Sri Lanka stand in this regard?

English continues to be extremely important especially where the major trading partners of Sri Lanka are concerned and in terms of the country’s interest in ascending to a more knowledge based economy. Sri Lanka has high achievements with regard to English language usage, which bodes well for anticipated further growth in service sectors such as tourism and leisure.

Given the increasing automation in virtually every sphere of life, which key skills must working people look to develop?

A mix of core (or soft) and technical (or hard) skills would best prepare people to benefit from the uncertainty surrounding an increasingly automated future of work. In terms of technical skills, science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM); ICT and coding; skills that help to adopt, operate and maintain technologies; skills that help create a business case, market and manage technology adoption; and non-automatable high manual dexterity tasks appear important.

As for core skills, individuals that possess creativity, emotional intelligence, social skills (interaction and care) would likely fare better in the job market.

At a broader level, it is clear that today’s workers need to continuously maintain their skills, upskill and/or reskill throughout their working lives.

Demographic changes, and the realities of globalisation and trade that drive supply and demand for the quality and quantity of jobs for men and women, also need to be carefully considered in shaping skills, and social and labour market policy.

How can social dialogue help mitigate and resolve past and emerging labour issues?

Social dialogue is defined by the ILO to include all types of negotiation, consultation or simply exchange of information between or among representatives of governments, employers and workers regarding issues of common interest relating to economic and social policy.

It is the ILO’s best mechanism in promoting better living and working conditions, as well as social justice. And it is an instrument, a tool of good governance in various areas. Its relevance is not merely related to the process of globalisation but in general, to any effort to make the economy better performing and more competitive, and society in general more stable and equitable.

Former Chief Economist of the IMF Olivier Blanchard demonstrated that consultations and negotiations between trade unions and employers at the firm or industry level could help economies adjust to economic shocks, and mitigate any adverse consequences for employment.

There is now increasing evidence to support this – including a recent ILO, OECD and Government of Sweden initiative called the ‘Global Deal,’ which sets out the business case for social dialogue. Seven key insights on how social dialogue can not only mitigate and resolve labour issues but also lead to increases in productivity, competitiveness and profitability offer inspiration.

Does child labour continue to be a major concern in the region as well as here in Sri Lanka?

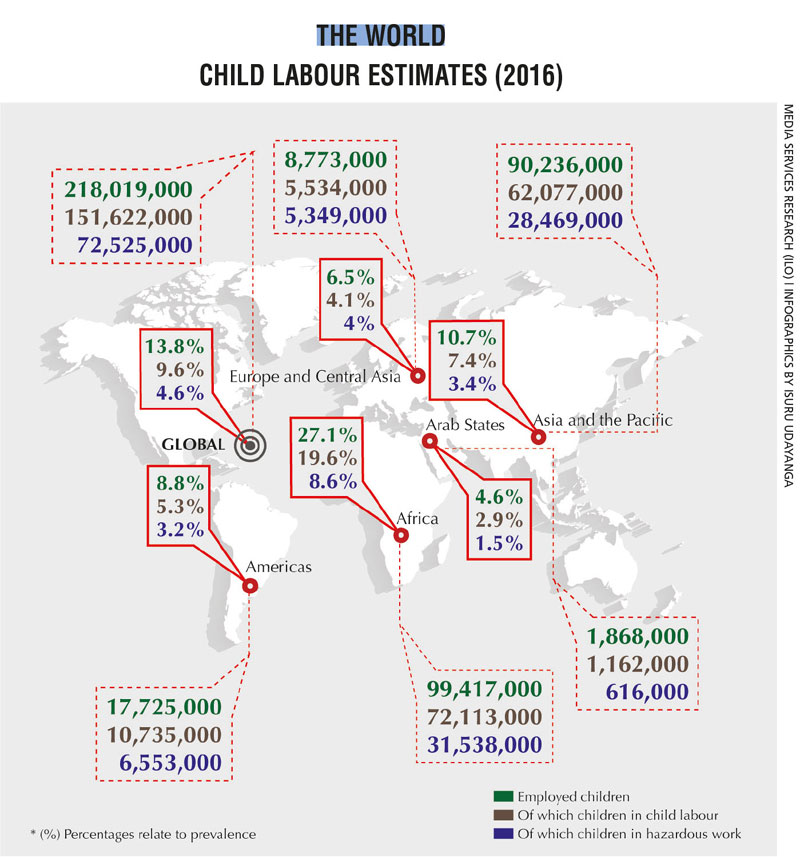

There are presently an estimated 152 million children aged between five and 17 in child labour around the world. Sixty-four million of these are girls and 88 million are boys. Altogether, that is almost one in 10 children in child labour globally. Asia and the Pacific is sadly home to 62 million child labourers.

According to an ILO supported Child Activity (National Household) Survey of Sri Lanka, there are 43,714 children in child labour, of which 39,007 are engaged in hazardous forms of work. This figure represents about one percent of the child population aged between five and 17.

As such, the incidence of child labour is relatively low (compared to many other Asian countries) but its total elimination has not been achieved and the risks of its reemergence are real if efforts lose momentum.

In 2016, the government committed to end the worst forms of child labour in the country. As a major milestone in the effort, a National Policy on Ending Child Labour in Sri Lanka was launched in September 2017 by President Maithripala Sirisena at a national event of his flagship programme ‘Let’s Protect Children.’

This type of commitment needs to be maintained so that Sri Lanka can become a proud country with zero child labour by 2025 – Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8, Target 8.7, calls for an accelerated elimination of child labour by this year.

Do you see real progress when it comes to assisting the ‘working poor’ and setting minimum pay scales? Is there ‘dignity of labour’ in this part of the world and the world in general?

Do you see real progress when it comes to assisting the ‘working poor’ and setting minimum pay scales? Is there ‘dignity of labour’ in this part of the world and the world in general?

The region has made remarkable economic progress as well as increasing labour productivity – albeit that growth is slowing down. Incomes have increased on average but not evenly.

In the Bali Declaration of 2016, ILO constituents in the Asia and Pacific region noted that while extreme poverty has declined and social protection coverage expanded, many challenges remain as millions of workers live in extreme poverty and over one billion are in vulnerable employment.

To reverse widening inequalities and the incidence of low paid work, countries identified policy priorities: investing in collective bargaining as a wage fixing mechanism, building on a minimum wage floor through social dialogue and sharing productivity increases.

In March 2016, Sri Lanka adopted a new minimum wage level for workers of Rs. 10,000 through the National Minimum Wages Act, No. 3 of 2016. It is the first time that a mandatory national monthly minimum wage was extended to all workers by all employers in the country (except for domestic workers).

Nevertheless, the best way to move towards a ‘decent’ minimum wage is through extensive social dialogue, periodic adjustments, and full consultation with the employers, workers and government – and with a balanced approach when setting the adequate minimum floor levels through evidence based analysis to tackle poverty and inequality.

India, through its Ministry of Labour, introduced a new Code on Wages on 10 August 2017. It seeks to consolidate laws relating to wages by replacing the Payment of Wages Act of 1936; the Minimum Wages Act of 1949; the Payment of Bonus Act of 1965; and the Equal Remuneration Act of 1976.

Through this new code, India’s central government may notify a national minimum wage for the country that will cover all workers, which is expected to benefit over 40 million workers. Previously, only scheduled employments were covered by the Minimum Wages Act, leaving behind a vast segment of the workforce without protection.

Pakistan’s constitution and legislative framework federally and provincially provides protection in relation to minimum wage entitlement. Each of the major provinces has Minimum Wage Boards, which determine minimum wages for unskilled – and in some cases, industry based – minimum wage levels.

Following devolution of labour related matters in 2010, Pakistan’s provinces have struggled to develop strategies in relation to wages and operationalise functional minimum wage setting boards to review evidence based wage setting. Nevertheless, most provinces are strengthening wage boards to set minimum wages in a technical manner.

ILO’s experience and global authority in wage policy concerns can contribute to construct better coordinated policies and strategies that can ensure a ‘just share of the fruits of progress to all.’ Advocating to extend coverage of minimum wages to all wage earners follows the standards set forth in ILO Convention No. 131 (Minimum Wage Fixing Convention, ratified by Sri Lanka as far back as 1975) through a process of thorough consultation with trade unions, employers’ organisations and government.

And can you explain the role of statistical and qualitative data in establishing and implementing policies pertaining to wages?

And can you explain the role of statistical and qualitative data in establishing and implementing policies pertaining to wages?

The collection of data and conducting studies is an essential part of a balanced and well-informed approach when setting a minimum wage. Statistical and qualitative data provide crucial information to enable a more sound or evidence based setting of minimum wages.

Indicators and relevant statistical information do not however, substitute for the equally important processes of social dialogue. Rather, they support well-informed social dialogue.

In wage fixing, data and indicators are required to assess the needs of workers and their families while also examining economic considerations such as requirements for economic development, and levels of productivity and employment.

In your opinion, what is the essence of a ‘great workplace’?

First and foremost and at a minimum, a great workplace is one where fundamental principles and rights at work are respected and enjoyed. Additionally, workplaces need to be safe, and where there is shared value between workers and employers – in simpler words, a workplace that is productive and where workers thrive.

Do existing labour laws ensure that the rights of workers are protected, and that the environment is conducive to productive and gainful employment?

Sri Lanka has ratified all ILO Fundamental Conventions that bar the use of child labour, forced labour and discrimination, and promote the right to freedom of association and collective bargaining. It has enacted laws in support of these and put in place cutting-edge, technologically advanced e-systems to facilitate effective labour inspection.

However, gaps continue to exist in terms of adequate scope and application of the laws, particularly given the high degree of informality in the Sri Lankan labour market and changing patterns of work.

Areas that could be strengthened include measures to promote greater gender and disability inclusion in the labour market (for example, by introducing flexible working times and places of work provisions), extension of social protection to those in the informal economy and migrant workers, and improved occupational safety and health provisions for all workers.

What is your take on the unionisation of workers in Sri Lanka?

Sri Lanka has a long and rich history in terms of the union movement with unions having been at the forefront of the national movement for independence prior to 1947. Today, there are over 2,000 registered private and public sector trade unions in Sri Lanka.

Individual unions are generally strong in representing the interests of workers in their respective sectors and giving them a voice.

The rate of unionisation is low despite the long history and importance of trade unionism in Sri Lanka, and trade unions will have to look to new ways to engage modern workers and convince them to join trade unions.

Greater female and youth representation in the union movement including leadership are areas that should be pursued. Given the large number of unions, a more federated approach to deal with labour issues would be important.

In terms of labour regulations particularly in Sri Lanka, what would you like to see going forward?

Regulations that promote or incentivise greater female labour force participation through flexible working hours and arrangements, for example. Sound analysis is also needed to arrive at a longer-term view (say by 2030) of where certain sectors of the economy are likely to grow, paired with demographic trends to better forecast where jobs will be created and legislative protections (and incentives) needed.

Given the significance of social norms in explaining gender gaps in labour force participation, labour laws accompanied by policy responses should address the root causes of occupational segregation, diversify employment opportunities for both women and men, and address the needs of workers to balance the demands of work and family.

Policy responses must also address discrimination both within and outside the workplace, and promote equal remuneration for work of equal value. Furthermore, the ratification of ILO Conventions on social protection, migrant workers, occupational safety and health, and promoting decent work for domestic workers, would be important steps to take and reflect in labour laws.

How can a better informed labour policy help drive entrepreneurship?

A policy that is based on sound analysis of the labour market supply and demand dynamics, and one which equally invests in developing the necessary tools and programmes that respond to the longer-term aspects of entrepreneurial culture, is extremely important particularly at the micro, small and medium-size enterprise (MSME) level where most jobs are incubated and sustainability is crucial. Therefore, several countries have launched MSME policies that aim to create an all-inclusive ecosystem to support entrepreneurship.

The ILO has supported the formulation of several MSME policies that have put the concerns of these enterprises on the agenda for all national issues especially in the areas of trade, monetary and fiscal policy. These policies have been informed by the needs of MSMEs to grow and focus on removing or lowering the obstacles for entrepreneurs, creating opportunities and providing a framework to expand business support services available to MSMEs.

The needs of MSMEs that can be addressed through informed labour market policies could be categorised as follows: business environment, business development and support services, market network and financing.

In the case of business environment, an informed labour policy focusses on understanding the hurdles faced by entrepreneurs in business registration or licensing, taxation and reporting, and simplifies these processes to improve the ease of doing business.

The ILO, through its Enabling Environment for Sustainable Enterprises tool, has worked with stakeholders to identify the major constraints hampering business development, and in turn reform the environment in which enterprises start up and grow.

With regard to business development and support services, an informed labour policy can strengthen entrepreneurship and make entrepreneurial activities more sustainable by improving the business management capacities of MSMEs.

The ILO has been rolling out its flagship business management training programme ‘Start and Improve Your Business (SIYB)’ since the 1980s to help individuals start and improve small businesses as a strategy to create employment.

SIYB’s objectives are to enable local providers of business development services to implement business startup and improvement training effectively and independently, and enable women and men to start viable businesses to increase the viability of existing enterprises – and in doing so, to create quality employment for others.

Here in Sri Lanka, the ILO has institutionalised the MSME support network by creating an SIYB Association whereby individuals trained in ILO entrepreneurship development tools can spread the support to potential and existing entrepreneurs.

In the context of improving market network and financing, informed labour market policies can drive entrepreneurship by improving MSME access to market opportunities and in the provision of adequate financing to support their growth.

Through its financial education programme, the ILO has supported governments and enterprises in the provision of and access to startup subsidies, as well as knowledge of financial tools.

And finally, what must the authorities and employers do to bridge the so-called ‘generation gap’?

Through its 2007 National Action Plan for Youth Employment and the 2014 National Youth Policy, the authorities have established the need to pursue the four ‘Es’ of equal opportunity, employment creation, employability and entrepreneurship. So the policy direction from the authorities is clear. Facilitating application of the policy is now essential.

For employers, investing in on-the-job training and mentoring with more senior staff is an important investment. Some promising programmes to this end already exist – for example, the Employers’ Federation of Ceylon’s National Network of Youth Initiative, which pairs undergraduate students with businesses to ‘learn the ropes’ through apprenticeships and mentoring. More of this needs to be done especially given labour shortages in key sectors of the economy. Promotion of self-employment programmes too – with formalisation as a conditionality – can make formal employment an attractive alternative for young people and their enterprises.

Leave a comment