THE SHARING ECONOMY

REAL-WORLD MATCHMAKING

Gloria Spittel takes cognisance of the sharing economy and what it offers

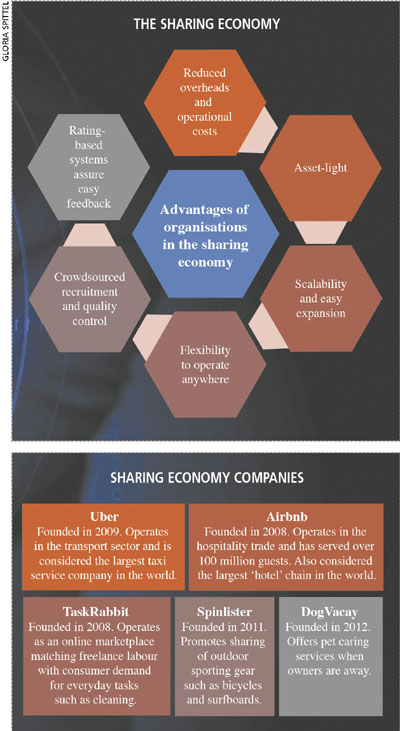

Captured thick in the midst of the sharing economy, the corporate world is grappling with rapid changes to how business is conducted. Challenges to the hitherto status quo are emanating from the internet-enabled sharing economy.

A term coined to describe business activity involving private members or peers brought together by a mobile app or website, whereby the third party charges a fee for making a perfect match similar to real-world matchmakers, the sharing economy has steadily grown in prominence, affecting and disrupting everyday life.

For instance, lawmakers in certain countries contend with questions of accountability, responsibility and regulation between platform owners or firms such as Uber, their ‘employees’ and the ensuing business transactions.

Perhaps born out of the global financial slowdown, an important differentiation between companies involved in the sharing economy from online marketplaces such as eBay, Etsy and Amazon is that transactions revolve around renting and not purchasing. The use of existing items sitting idle or excess capacity for a fee has made the sharing economy a novel approach and a necessity.

In and of itself however, renting is not a new concept as seen by the abundance of car rental firms and hotel rooms. But the departure from existing rental-based business models to those thriving in the sharing economy marks the absence and removal of the need to build infrastructure.

On the surface, the sharing economy seems an ideal solution to consumerist mentalities that acquire but underutilise goods. It has had the effect of reducing the cost of ownership for both parties involved, increasing convenience and improving productivity, and limiting environmental damage where goods are rented rather than purchased.

But as with all concepts, the sharing economy has caused some grievances to existing labour pools, owners of businesses, traditional business models and existing laws.

For instance, there’s been opposition to Uber by traditional taxi drivers and firms in countries such as France, the UK and Canada. The disruption to livelihoods has been an undesirable effect of Uber’s rise globally. This disruption is true of all organisations in the sharing economy ecosystem.

How does an entrenched large organisation complete with fixed and high operational costs and liabilities compete with a flexible, organisationally light and low-cost company?

For some, the answer is in imitation – or rather, an attempt to ‘modernise’ service offerings and meet market demands.

For example, it is not unthinkable for car rental firms to offer underutilised or idle vehicles as part of a hybrid business model. While companies such as Turo (formerly RelayRides) will not eliminate car rental firms completely, they can cause the incumbents to analyse their operational strategies to offer tactical developments.

But imitation is not only a one-for-one game; organisations should consider ‘sharing’ underutilised premises, machines and other facilities, and even intellectual capacity.

A particularly reliable competitive strategy involves trust and reputation. Existing companies can leverage their reputation amongst the client base especially if they’re sceptical about change. For instance, those who book hotel stays through Airbnb may do so for a plethora of reasons ranging from convenience to security; it is up to the organisation to decipher these reasons and target that specific audience.

However, this strategy may lead to failure if it is deemed predatory against new business competition, or where a company mistakenly assumes it is held in high regard by clients or that its brand proposition is trustworthy when customers think otherwise.

A common strategy is communication. But this is not only through traditional means such as press releases and advertisements because feedback is an essential component of business; organisations should no longer disregard client feedback on a service or product and instead engage with the client to improve any shortcomings. This is important because rating systems on apps such as Uber provide clients with a sense of empowerment, both perceived and real.

Of course, incumbent organisations can compete by reducing prices. But this can devalue the incumbent’s existing brand identity or value, and communicate desperation – or worse, an ineptness to compete. Resorting to a price war drives the focus away from innovating sustainable solutions to short-term gains.

The option to invest in rival firms offering the same service in the shared economy is a strategic move that keeps the incumbent focussed on its core business while providing a foothold in new trends and the manner in which its core business is conducted, or morphing to suit market appetites. This is particularly smart when resources are limited and focussing on the core business necessitates success.

But when an incumbent decides to compete with new businesses in the sharing economy, competition and an open and positive approach to change are important. If existing organisations are to rely on reputation and current stability, they may stagnate and surrender market positions that can be useful for discussions on shaping regulatory and policy frameworks.

This inevitably becomes another approach to competing and staying relevant in the technologically driven, ever-changing world of business.

Very true, and this would be the way forward. This will ensure reduced overheads and operational costs which could be achieved through eliminating possible duplication of allocating scarce resources.