SPLIT TIES: THE GULF IN CRISIS

Samantha Amerasinghe analyses the potential economic fallout from the Gulf standoff

The Arab world’s only trade bloc the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is at risk of disintegration following Saudi Arabia and its three allies announcing on 5 June thatthey have severed diplomatic ties with Qatar.

The Arab world’s only trade bloc the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is at risk of disintegration following Saudi Arabia and its three allies announcing on 5 June thatthey have severed diplomatic ties with Qatar.

Qatar is the world’s leading exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and the GCC’s richest nation in per capita terms. The political rift between Qatar and the GCC could have significant economic implications – it could lead to long-term issues for the functioning of the GCC if the standoff persists for a protracted period.

Last year, the new power behind the Saudi throne Prince Mohammad bin Salman praised the potential of the Gulf’s trade bloc. He said the GCC could become one of the world’s largest economies if its members strengthened integration. The GCC, which includes Kuwait and Oman, was formed in 1981 as the Sunni-led Gulf monarchies sought a united front against the perceived threat from Shia Iran two years after the revolution.

Progress has been slow but with a combined GDP of US$ 1.4 trillion and about 36 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves, the GCC became an important and rare platform for cooperation in a highly volatile and unstable region. A customs union was agreed in 2003 and a common market five years later.

Intra-GCC trade has grown 15 percent a year over the past decade, according to a report by EY Consultancy. But the unprecedented embargo imposed on Qatar by Saudi Arabia and its allies looks set to undermine the GCC, and the core tenets for which it stands. This political rift comes at a time when the Gulf is enduring headwinds. The slump in oil prices has forced governments to drastically reduce spending, suspend projects and dig deep into their foreign reserves. The embargo imposed on Qatar includes the closure of land crossings, as well as airspace and sea access.

Therefore, the economic implications for Qatar could be significant: Qatar’s economy will be impacted through three channels – viz. foreign trade, inflationary pressures and the ease of doing business.

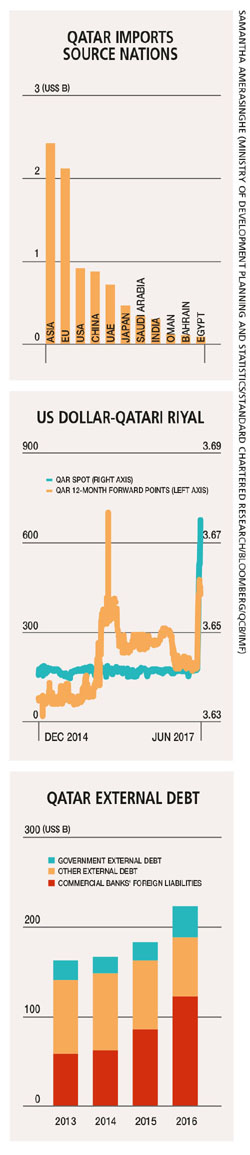

Qatar’s trade will likely take the biggest hit. Imports from its leading sources – Asia (excluding Arab countries), the European Union (EU) and the United States – may need to be rerouted as Saudi Arabia closes its vital land crossing with Qatar. Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain are not the leading sources of Qatar’s imports but account for 15 percent of its total imports, which may come to a stop as a result of shipping disruptions.

Rerouting of trade could well take time and raise the cost of imports, and thus lead to higher consumer inflation. Trade rerouting is likely to increase food prices that comprise approximately 13 percent of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket. And construction costs could increase given that key building materials such as concrete, aluminium and steel entered the country by ship, as well as land, from Saudi Arabia.

Qatar’s oil and LNG exports have been mostly unaffected so far by transport links between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Qatar being cut. LNG tankers have maintained their regular routes to destinations, which are primarily in Asia and Europe. It has also been able to obtain imports from alternative sources, which includes food from Turkey.

While Qatar’s crude exports are much less than those of its neighbours, its LNG exports account for 30 percent of the global demand – they predominantly end up in Asia (this accounted for 72% of LNG exports in 2014), followed by Europe (23%). LNG tankers heading to Europe appear to be maintaining their course through the Suez Canal, which is governed by an international agreement.

As Qatar is a small producer of oil compared to the trio of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the price of oil is unlikely to be seriously affected by this political fallout.

One of the key challenges has been the surge in the US Dollar-Qatari Riyal (QAR) spot rate with a one percent differential over the peg rate of QAR 3.64 to the dollar, at the time of writing. Capital outflows from Qatar have accelerated following the rift with the GCC, resulting in this divergence.

So what are the medium to long-term implications of this rift?

To deliver on its 2022 FIFA World Cup undertaking, Qatar will now need to amend its development plans, securing imports of building materials from alternative channels. Business models of key industries including aviation will also need to adapt to the new realities. Qatar’s government has been borrowing to help finance infrastructure spending as it prepares to host the World Cup but raising external debt will become more expensive.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain have stated that restoring ties with the Qatari government would require Qatar’s full compliance with the ‘Riyadh Complementary Arrangement’ that GCC members signed in 2014. So far, they have not signalled any room for negotiation to settle their differences.

Efforts to resolve the crisis from within the GCC will be increasingly reinforced by international mediation led by US and EU member states.