FOOD SECURITY

THE BURDEN OF MALNUTRITION

Yamini Sequeira underlines the imperatives of nutrition sensitive agriculture and food systems

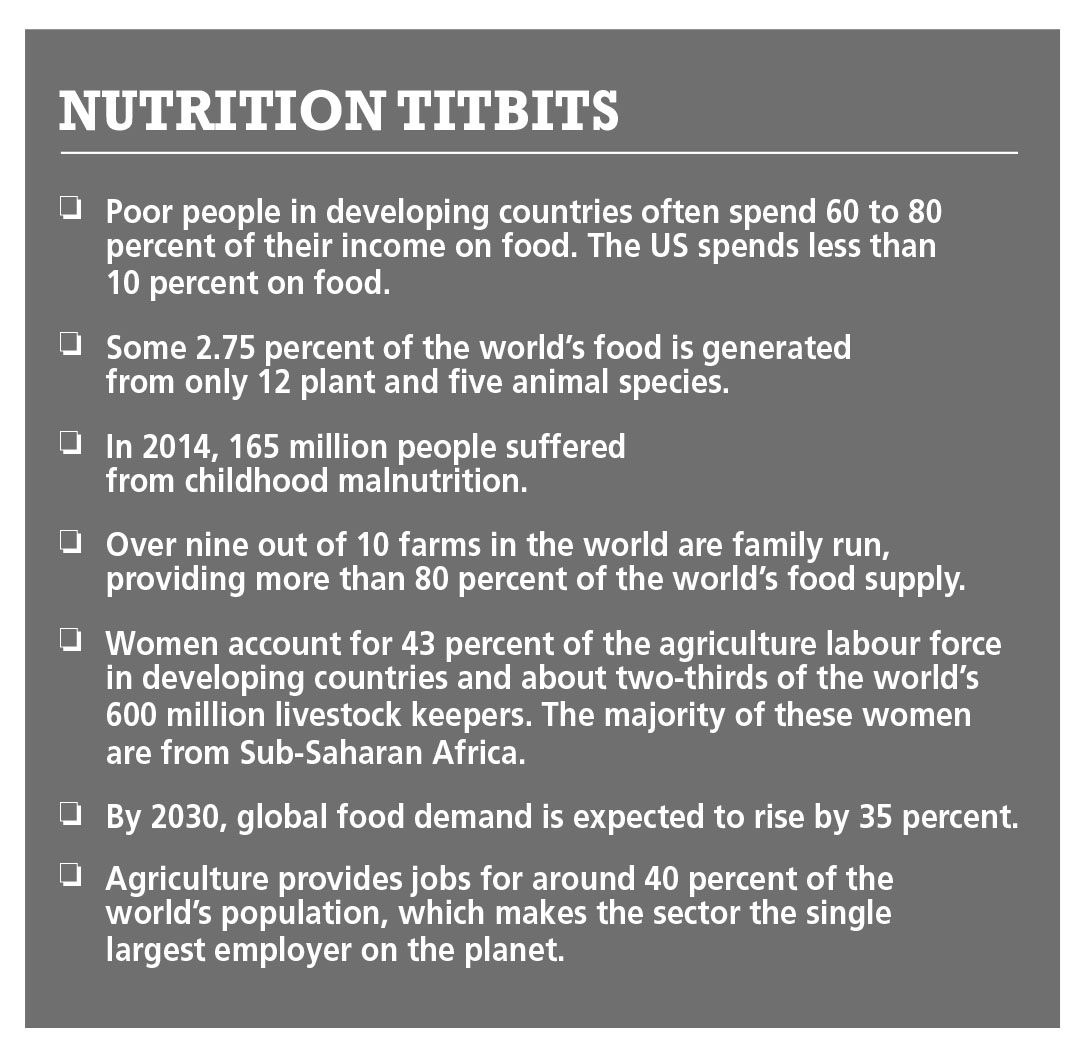

Global undernourishment has been on the rise since 2014, reaching an estimated 821 million in 2017. It’s clearly a long road ahead to achieve the targets for 2025 and 2030 – viz. reducing stunting in children under five, anaemia in women of reproductive age and low birth weight; limiting the number of overweight children; increasing the rate of exclusive breast feeding; and controlling childhood wasting.

The World Congress on Food and Nutrition in December focussed on ‘Discovering the new advances on food and nutrition for the new generation.’ While the focus of the conference held in Dubai was on nutritional advancements, the reality for millions of global citizens is another story.

Levels of childhood stunting and wasting persist across regions and countries. Yet, there’s been a simultaneous increase in obesity among children – often in the same countries and communities with relatively high levels of infantile stunting. This coexistence of malnourishment with obesity and being overweight is commonly referred to as the ‘double burden of malnutrition.’

A large proportion of the world’s population is also affected by micronutrient (vitamin and mineral) deficiencies, often called ‘hidden hunger’ because there may be no visible signs. Iron deficiency anaemia in women of reproductive age is one form of micronutrient deficiency.

Poor access to food (particularly healthy food) contributes to undernourishment as well as obesity. It increases the risk of low birth weight, childhood stunting and anaemia in women of reproductive age – and is linked to overweight girls of schooling age and obesity among women, particularly in upper middle and high income countries.

The Director-General of FAO José Graziano da Silva has been quoted as saying that “we must empower, encourage and educate people to adopt healthy diets.”

Da Silva continues: “Parliamentarians play a very important role in this process since they are responsible for passing laws and supervising budgets. It is up to them to guarantee that food and nutrition security is at the top of the political and legislative agenda. We need good governance and specific legislation, to promote food security and improve nutrition.”

Access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food must be framed as a human right with priority given to the most vulnerable.

The FAO urges that policies must pay special attention to the food security and nutrition of children under five, those of schooling age, and adolescent girls and women in order to halt the inter-generational cycle of malnutrition. A shift is needed towards nutrition sensitive agriculture and food systems that provide safe as well as high quality food. This would promote healthy diets for all.

Turn the spotlight on Sri Lanka in the context of food and nutrition, and the statistics from an FAO report speak for themselves: 4.7 million people of Sri Lanka’s 21 million population don’t have sufficient food to sustain a healthy life.

Sri Lanka is ranked poorly by the Global Hunger Index and Global Food Security Index. Based on FAO statistics, the level of calorie deficiency in Sri Lanka (192 kcal/capita/day on average in 2014-2016) is the highest in South Asia. Only Afghanistan is behind Sri Lanka in terms of undernourishment in South Asia.

The lack of food security in Sri Lanka has led to a high prevalence of developmental and growth issues such as stunting (low height for weight), wasting (low weight for height) and weight, the key indicators of a country’s nutritional status.

Sri Lanka suffers from high levels of stunting (13.1%), wasting (19.6 %) and being underweight (23.5%) among children less than five years of age. It faces the third highest prevalence of wasting in the world, only behind Djibouti and South Sudan. And the incidence of wasting in Sri Lanka has increased from 11.7 percent in 2009 to 19.6 percent in 2012.

The population in the plantations sector in the Central Province and communities in the previously war-torn Eastern Province report the worst levels of malnutrition in the country.

Food for thought, indeed…