STATE OF THE NATION

PERSONALISM: SUPREME WRIT’S NEW FACE

Wijith DeChickera asserts that tinkering with a country’s constitution – not for the first time – is taking on a particular political agenda

There is a tide in the affairs of men, which taken at the flood, leads on to fortune. The immortal Bard of Avon penned that thought around 421 years ago. His character Brutus in the play Julius Caesar suggested that fortune favours the bold, brave, brazen campaigner who seizes the opportune moment.

Today, the tide is taking another Caesarean battlefield – Sri Lanka is not Shakespeare’s “other Eden, demi paradise” along a particularly rapid current of a strong antidemocratic ebb.

The chief concern of the government of the day seems to be to secure and safeguard political power for itself and its protagonists. This is nothing new since governments of the day from autocratic to technocratic have pursued similar strategies to consolidate their respective positions.

That Sri Lanka’s first executive president J. R. Jayewardene did it in 1978 in a way that retained his Grand Old Party in political power for 17 long and often tyrannical years – should be a cautionary tale now for those who would pointedly tinker with constitutions.

Of course, the experiment by his political and personal heir – erstwhile and many times premier Ranil Wickremesinghe in collusion with former president Maithripala Sirisena in 2015 ended rather more precipitately. Some, being enamoured of constitutional checks and balances against authoritarianism, would even venture to say that it ended poorly and prematurely that is, for a nation state where nationalistic populism raises its head so often and quickly after a lull…

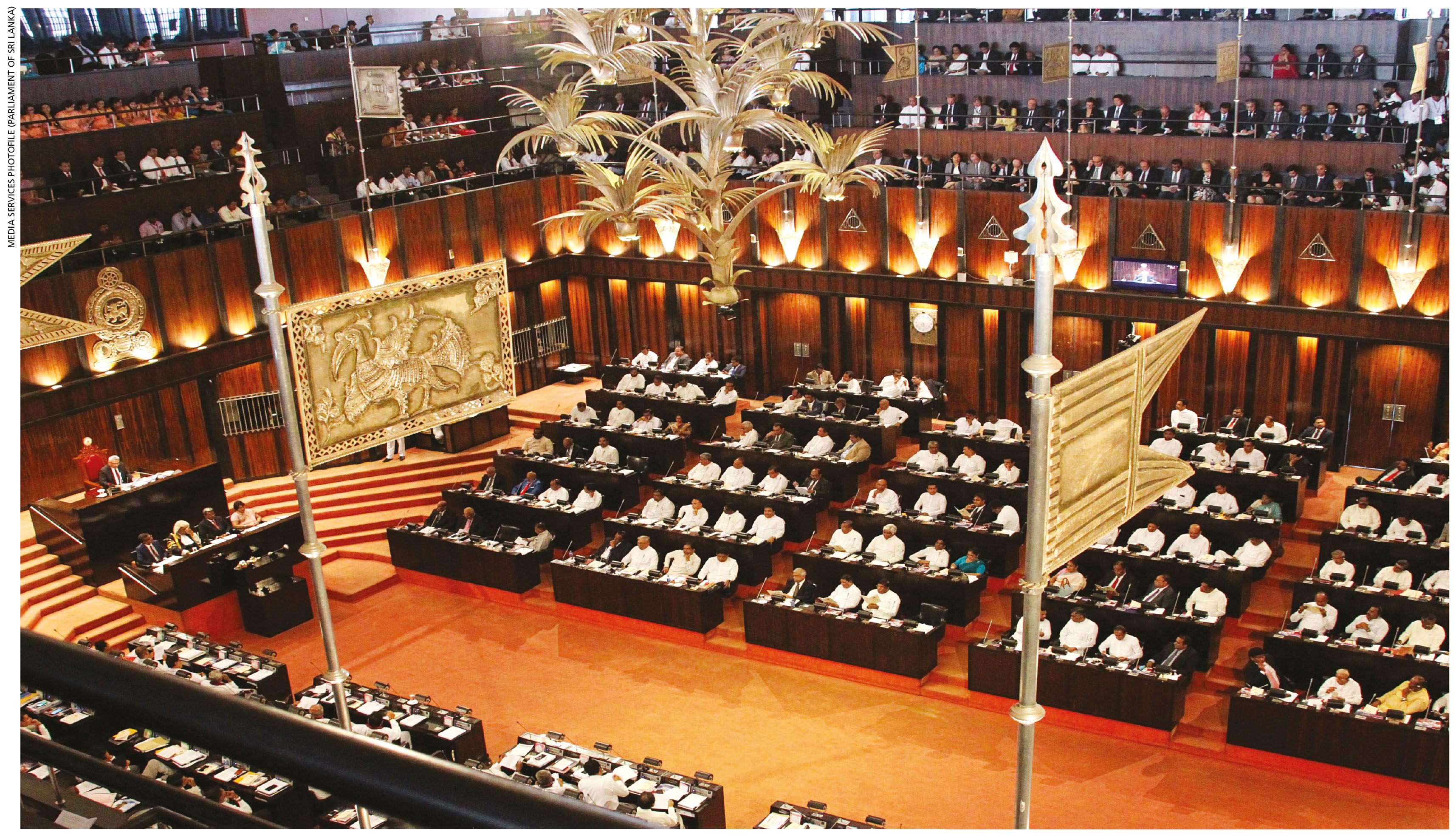

In all, the former Crown Colony of Ceylon has undergone 19 and now 20 constitutional amendments in the relatively short space of 72 years since independence. We have had seven prime ministers as heads of state, an equal number of presidents as chief executives and 16 parliaments.

All things being equal, this may suggest a healthy movement of power between parties of diverse (more than one ideology) or at least (two) different persuasions?

However, in terms of the ethos of the constitutions that helmed the ship of state (1947, 1972, 1978), there has been more of a pendulum effect than pure exchange and transfer of power between personalities and their parties.

In particular, the most recent amendments to our second republican constitution – the 17th, 18th, 19th and now 20th have seen the character of supreme writ swing between ‘government by executive’ and ‘government by legislature’ broadly speaking.

FORM The constitution of any country should not be about the zeitgeist alone. Rather, the law of the land could better serve the larger interests of the people than any cabal, claque, commercial enterprise, economic coven or other egregious concern that privileges the personal over the collective.

It was so in 1978 and 2015… and it remains to be seen after all has been said and done to trim and tailor 20A in 2020 – whether it will be so again.

In terms of form, at least some of the salutary changes introduced in 19A have been retained in the proposed 20th. These include the two term limit, term of office for the presidency and the right to information bill. However, significant new clauses militating in favour of strengthening the chief executive’s hand in key national appointments signal a turn to hyper-presidentialism. Here, a far stronger head of state will hold virtually all the keys of the kingdom with a firmer grasp than ever…

FUNCTION This begs the question of the purposive nature of the constitution in general and the amendment at hand in particular.

It seems fairly certain from the tweaking of the general election ambit along the campaign trail which went from consolidating power for a stronger government to constitutional privilege for a stronger governor – that the 20th is a ‘personalist’ expression of this administration’s interpretation of the mandate handed to it in August. Given the majority that it enjoys, government – in the face of a decimated opposition could have pulled through the next five years any legislative imperatives it wished to enact with relative ease.

Now however, the nationalistic populism that threw open the floodgates for constitutional counter-reform may well give certain governors that extra push to drive the nation in any direction they please… with few if any constraints on the presidency going forward. If 20A finds popular approval?

FUNDAMENTALS The result of the 2020 general election revealed the disdain of the electorate for government by often flawed commissions, which were made futile by an effete balance of power between president and prime minister that led to disaster especially 4/21.

This has led to a strong current in favour of hyper-presidentialism where government would be led by executive will. If the constitutional process in place in recent weeks works to ratify this major law, it will change the lie of the land in no insignificant measure.

It won’t be Brutus but rather Caesar seizing the day.

Leave a comment