OIL INDUSTRY

CHANGE IN THE PIPELINE

Samantha Amerasinghe examines the implications of the OPEC+ oil agreement

A change in the oil industry is imminent. An agreement between OPEC and its allies reached in July – to raise oil production in response to soaring prices – was a welcome compromise given that the rift between Saudi Arabia and the UAE over oil production baseline targets posed a risk of the latter leaving the OPEC+ group.

More importantly, such rifts in the longer term raise serious concerns about the cartel’s ability to rebalance and stabilise oil markets as the energy transition gains momentum.

Thankfully, a deal was reached but what’s at stake for OPEC+ members in the face of dwindling demand given that there’s a growing belief the peak in demand for crude oil will occur in the next decade or so?

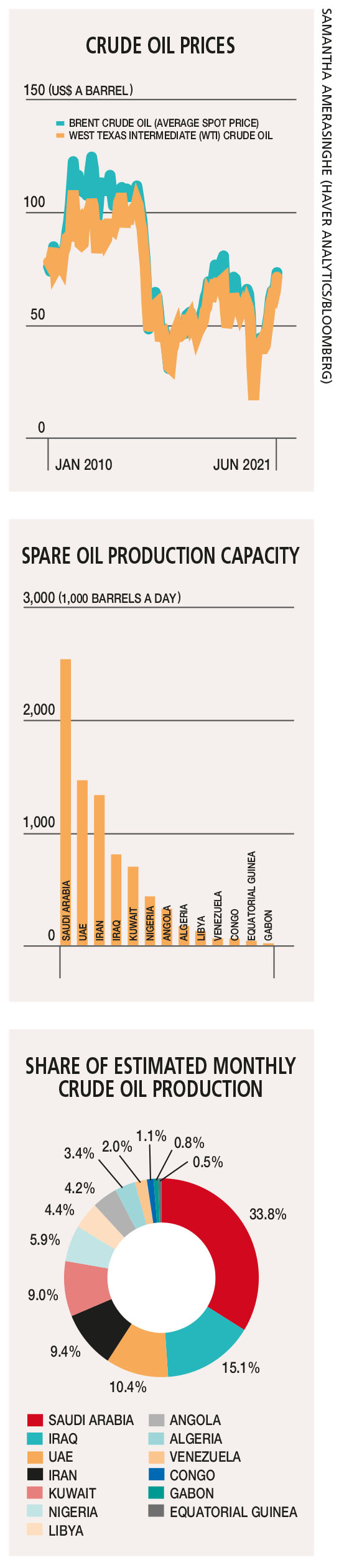

OPEC+ introduced severe production cuts last year as the pandemic spread and demand for fuel plummeted, resulting in oil prices collapsing to below US$ 30 a barrel. The cartel slashed production by almost 10 million barrels a day at the height of the lockdowns and travel bans in April last year but has gradually increased production as economies reopen.

In July, OPEC had to adapt to a new reality after tight supply pushed the price of Brent crude oil (the international oil benchmark) to its highest level (75 dollars a barrel) in three years as demand recovered. About 5.8 million barrels a day of output still remains off the market but that level is expected to be largely returned as OPEC+ has set a target for restoring the output cut during the early days of the pandemic by the end of next year.

In July, OPEC had to adapt to a new reality after tight supply pushed the price of Brent crude oil (the international oil benchmark) to its highest level (75 dollars a barrel) in three years as demand recovered. About 5.8 million barrels a day of output still remains off the market but that level is expected to be largely returned as OPEC+ has set a target for restoring the output cut during the early days of the pandemic by the end of next year.

As part of the agreement, members of the OPEC+ group – including the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iraq and Kuwait – will be awarded higher production baselines, which is the level from which output deals are calculated.

For example, under the agreement, the UAE’s production baseline – which it has complained failed to reflect its rising production capacity – will rise to 3.5 million barrels a day from about 3.2 million.

Nonetheless, the modest pace of output increases is a sign of OPEC+’s lingering concerns about the strength of the global recovery as COVID-19 variants continue to emerge. It also suggests that oil producers are relatively comfortable with the prevailing price of crude and oil prices are likely to remain elevated for some time.

In fact, some oil traders and industry experts believe the rate of increasing production is too slow to stop the market from tightening.

So are higher oil prices likely to hamper the global recovery?

Recently, the International Energy Agency (IEA) warned that rising oil prices could begin to drag the economic recovery unless OPEC moves swiftly to increase supply. However, the anticipated strong post-pandemic growth and consumer demand (unless COVID-19 variants wreak havoc once again) in developed markets should help cushion the blow from costlier crude oil.

The cost of oil as a share of GDP is a bellwether for oil’s impact on growth. According to a recent report by a US bank, the indicator is expected to rise to 2.8 percent of world GDP this year while remaining well below the long-term average of 3.2 percent (assuming an average price of US$ 75 a barrel this year).

Moreover, the IMF projects the global economy will grow by six percent in 2021 – the fastest pace in at least four decades – and this should enable nations to weather the impact of higher oil prices quite well.

Developed economies are much less vulnerable to oil price increases than they were decades ago because services – which consume less oil than heavy industries – account for a larger share of output while emerging markets will face a more challenging outlook.

China’s economy will be the exception with real GDP growth projected at around eight percent. Although higher oil prices have weighed on some imports, domestic demand remains robust and Chinese refineries are ramping up domestic output to alleviate the pressure from higher global prices.

However, many other emerging markets such as India and Turkey are more exposed, as food and energy comprise a higher share of spending. In India for instance, a 10 dollar increase in oil prices will add 0.5 percent of GDP to its current account deficit, according to analysts’ estimates.

Although a deal was struck, more disagreements (which are not unusual among cartel members) and price volatility will be common. This is because OPEC+ members are adopting divergent strategies to address the energy transition and oil markets.

The IEA has a range of scenarios that suggest oil demand in 2030 could be about 105 million barrels a day (about 5% higher than before the pandemic). Or if governments get aggressive in tackling climate change, it could fall to as low as 85 million barrels a day.

Energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie believes that under aggressive climate scenarios (i.e. meeting the Paris Agreement targets), oil prices could fall to about US$ 40 a barrel by 2030.

Confronted by dwindling demand, some major oil producers such as the UAE want to boost supply and monetise oil reserves in quick time while others like Saudi Arabia prefer to restrict production to keep prices high.

As we rapidly move towards a greener economy, change is in the offing but the future remains uncertain.

Leave a comment