MOTOR INDUSTRY

Compiled by Yamini Sequeira

PATH FULL OF POTHOLES

Samantha Rajapaksa says ad hoc policies are stifling the industry

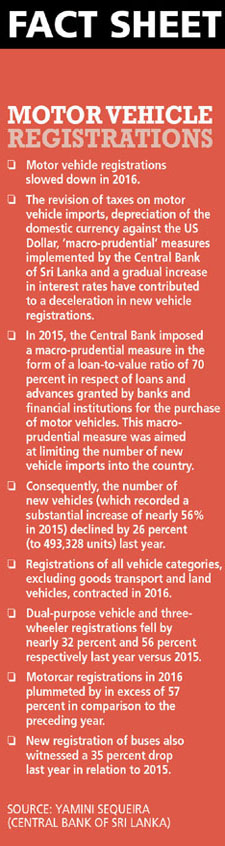

The motor industry here in Sri Lanka has been in a miasma of uncertainty for a while. Over the past year and a half, there have been numerous policy changes to customs duty, the loan-to-value ratio and import regulations. The combined effect of these amendments has thrown the industry into turmoil.

On the present state of affairs, the Managing Director of Associated Motorways Samantha Rajapaksa states: “Currently, the industry is at one of its lowest phases in recent history with a record decline in business.”

“I understand the need to improve the country’s balance of payments position but such implementation should be carried out in a more planned manner that doesn’t suddenly impact the industry adversely. After all, many other related sectors are then adversely impacted in a domino-like effect.”

SHIFTING GOALPOSTS He cites sales in 2015 and 2016, noting that “there’s about a 60 percent decline in passenger vehicles.”

Rajapaksa continues: “Following the initial introduction of the loan-to-value ratio where customers originally paid a 30 percent down payment, it was increased to 50 percent with effect from 1 January. This led to a 53 percent drop in sales in the first three months of this year compared to the last quarter of 2016.”

“So the loan-to-value ratio has become a key challenge because not only has it slowed automotive sales but also thrown the industry into a quagmire,” he adds.

Even the trading stock brought into the country by companies is currently selling only gradually because customers are unable to purchase vehicles due to the requisite high down payment.

TRADE PRACTICES Today, to purchase an entry-level car, the average household needs approximately Rs. 1.1 million for a down payment. This has caused a sharp decline in the total entry-level segment.

The government’s reasoning is that the economy is overheating and credit growth is a factor. But studies indicate that by and large it’s non-trading activities that have contributed to credit growth in the country.

Rajapaksa explains: “Unfortunately, these actions have led to a drastic drop in vehicles sales. This has also impacted foreign direct investment (FDI) as automotive companies here have significant foreign ownership. And of course, when they encounter business-unfriendly policies and the manner in which they’re executed, their willingness to invest diminishes. To attract FDI, you need stability in the policy framework.”

He explains that “another key issue hindering the motor industry is the valuation methodology used at the point of importation. Sri Lanka has one of the largest duty structures in the world, which places vehicles beyond the reach of the average consumer.”

And Rajapaksa points out, there is a duty of 255 percent on small entry-level cars. Coupled with the new loan-to-value regulation and absence of efficient public transportation, “the average Sri Lankan is deprived of convenient and affordable transportation choices.”

“Although the unit rate valuation system based on engine capacity was introduced to circumvent undervaluation at the point of importation, this is a deviation from global vehicle trading norms where valuations are based on cost, insurance and freight (CIF), and manufacturer’s value,” he asserts.

Rajapaksa maintains that “this has resulted in anomalies where we find the price difference between high-end and other mid-range vehicles to be minimal, which means that some brands have an unfair advantage.”

So according to him, the current valuation system can be deemed “an unfair trade practice while undervaluation practices appear to continue. The only solution is to revert to globally established trade practices along with the proper enforcement of import laws.”

WHITHER TRANSPORT? Transport is a basic human need and a government’s duty is to facilitate this, Rajapaksa argues. He maintains that restricting ownership of vehicles is not the solution – managing the cost of ownership and usage is what will make a difference.

He notes that “traffic congestion is an urban issue. Other countries have tackled this challenge by imposing tariffs for entering city areas during peak times, requiring a minimum number of passengers and so on.

“There are many ways in which vehicle usage can be managed – for example, by making the cost of usage a deterrent despite vehicles being affordable! Another key factor is to raise the requisite driving skills and standards for obtaining a new driving licence. Incompetent drivers are a major contributor to road congestion and accidents,” he notes.

Overall, Rajapaksa avers that the government is aware of the challenges that the industry faces.

And he is hopeful that the powers that be will take a fresh look and review policies with a view to elevating the state of the motor industry.

ECO ENVIRONMENT Looking to the future, a looming challenge for the country will be the lack of adequate provisions to dispose of used batteries in hybrid and electric cars.

Rajapaksa cautions: “While there’s an influx of hybrid and electric cars, there is no policy for disposing of used batteries. Electric and hybrid cars are more eco-friendly but a lack of regulations for strict recycling and safe disposal of batteries will lead to them ending up in marshes and garbage dumps, leading to major environmental issues.”

LONG-TERM VISION In the case of emission standards, Sri Lanka does not have a stated long-term vision or policies unlike some countries that boast engine emission standards of Euro 5 and above. This is yet another area that needs urgent attention if Sri Lanka is to curb pollution, and improve and conserve air quality in the long term, he warns.

In his view, it would be fair to say that the automotive industry is facing a mountain of challenges. The industry is seeking long-term policies and a level playing field. And perhaps the government also faces a quandary: how does it offer relief without suddenly fuelling demand?

In conclusion, the ad hoc nature of policy-making for and on behalf of the motor industry is painting a rather negative picture of the country among potential investors.

As Rajapaksa sums up: “We work with more than 10 reputed global organisations with long-term planning horizons for their markets. But given the lack of a stable policy outlook, these investors associate the country with volatility and high risk.”

“At this point in time, the future for the automotive industry appears bleak!” he avers.