Q: In your view, has the aragalaya led to a united Sri Lanka – and if so, is this unity sustainable?

A: Yes. Initially, I was sceptical of the movement’s longevity. Would the aragalaya have occurred at all if the middle class and the rich had not been affected by shortages of medicines, fuel and food, and power outages?

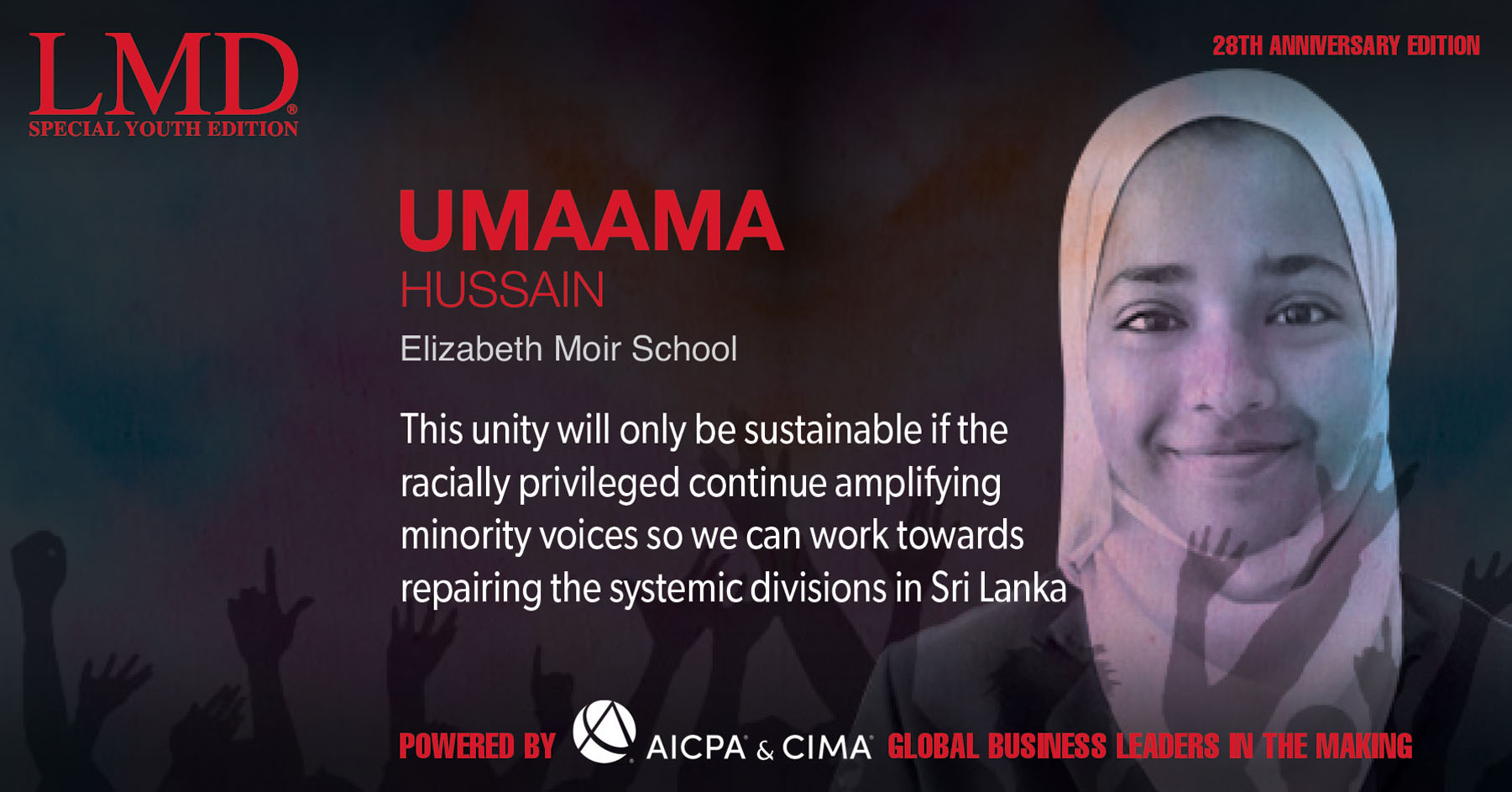

But now I have hope when I see GotaGoGama with its focus on including people of all religions, ethnicities and classes. However, this unity will only be sustainable if the racially privileged continue amplifying minority voices so we can work towards repairing the systemic divisions in Sri Lanka.

Q: How will you be the change you want to see?

A: When I was 12, I wanted to be the president. I was going to power buses with solar panels, start schools at 10.30 a.m. and improve women’s lives. I told my mother this – and she told me I had to become a Sinhalese-Buddhist man first. She wasn’t wrong.

At 17, I don’t want to be the president anymore; but I do want to help improve this country. Politics has always been considered ‘dirty work’ – but I know now that politics is personal.

I would like to address government policies that add to ethnic and language divisions, and contribute to institutionalised racism. I would also help develop reforms for safer public transportation, poverty reduction, better access to birth control and sex education.

Q: As far as our education system goes, what are the pros and cons?

A: Sri Lanka has free education, increasing accessibility and improving literacy rates – but educational reform is long overdue.

Any household income saved on schooling is spent on private tuition so students can pass exams (a system that deliberately sets the odds against students for the sake of determining a Z score that mimics fairness rather than perpetuating it) while government spending on education has greatly diminished.

Additionally, the separation of schools based on race, religion and gender hinders the freedom to express these identities, and creates divisions, contributing to institutionalised racism and sexism.

Q: Do you see yourself remaining in Sri Lanka – or returning to Sri Lanka – or do you think it’s best to migrate?

A: Growing up, it was never a consideration that I would remain in Sri Lanka. But as one who wishes to pursue astrophysics, the country lacks the opportunities and facilities to thrive in such a field.

So the conversation around youth remaining to improve the country wasn’t something I ever thought I’d have to worry about. Given the volatility of the prevailing situation, I cannot honestly say whether I would return to Sri Lanka after my higher education, although some part of me will always want to – because if not I, then who?

MESSAGE TO THE YOUTH

Start small and close to home – don’t feel overwhelmed by the crisis’ immensity and need to ‘fix’ everything.

SRI LANKA: FIVE BURNING ISSUES

Education system

Brain drain

Institutionalised racism and sexism

Freedom and safety of the press

Government transparency

ROLE MODEL

Vraie Balthazaar – Being a feminist and political activist, she taught me that the ability to say politics is not important to you (as a citizen) is a privilege. Because that means you are of a class or race where government policies do not directly affect your life through for example, educational or agricultural policies. And she deepened my knowledge of how women are affected by the political and education systems.

SUMMARY

Politics is personal – don’t shy away from discussions and involvement in it – and if you have the privilege of being able to protest and use your voice, do so.