GLOBAL ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

EMERGING MARKETS AT RISK

Samantha Amerasinghe explains why this year’s global growth could falter

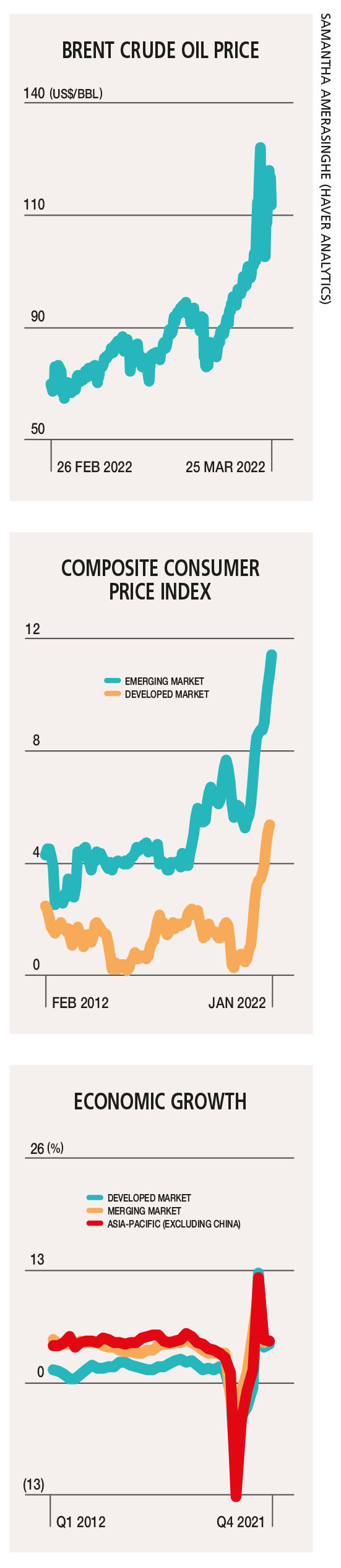

Slower growth and more rapid inflation sum up the outlook for the rest of the year. Even though there was a sense of optimism for global growth with the pandemic receding, the war in Ukraine has resulted in such projections being slashed.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) cut its latest global growth projection (i.e. the average rate of growth) by one percentage point to 2.6 percent, which is down from 5.5 percent last year.

Higher food and energy prices coupled with supply shortages will be the immediate pain points for low and middle income economies. Russia and Ukraine are major producers of commodities, and the war caused global prices to soar – especially for oil and natural gas.

Many of the world’s developing economies have struggled to recover from the pandemic, unlike developed countries that have seen growth bounce back – albeit slower than expected. UNCTAD says that by 2023, economic output in developing economies will still be four percent below their projected levels prior to the pandemic.

Many of the world’s developing economies have struggled to recover from the pandemic, unlike developed countries that have seen growth bounce back – albeit slower than expected. UNCTAD says that by 2023, economic output in developing economies will still be four percent below their projected levels prior to the pandemic.

Total debt in these countries now stands at a 50 year high. Inflation is at an 11 year high and 40 percent of central banks have begun to raise interest rates in response. The Ukraine crisis could make it harder for many low and middle income economies to regain their footing.

Although all regions of the global economy will be adversely affected by the war, major commodity exporters will likely do well from the rise in prices. However, the EU will probably see a major downgrade in its growth performance this year as will many parts of Asia.

Some developing economies are heavily reliant on Russia and Ukraine, which supply more than 75 percent of the wheat imported by a handful of countries in Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

Russia is also a major force in the market for energy and metals; it accounts for a quarter of the market for natural gas and 11 percent for crude oil.

Estimates in a forthcoming World Bank publication suggest a 10 percent oil price hike that persists for several years can cut growth in commodity importing developing economies by a 10th of a percentage point. Oil prices have risen by more than 100 percent in the last six months.

Emerging countries will be impacted along three main channels.

First, higher prices for commodities such as food and energy (oil and natural gas) will push up inflation further. For those emerging markets (EM) that are net commodity importers, higher prices will pressure external accounts and weigh on currencies.

The greatest impact on current accounts will be on petroleum importers including ASEAN economies and India. For China, the immediate effects should be smaller because fiscal stimulus will support this year’s 5.5 percent growth goal and Russia buys a relatively small portion of its exports.

For lower income EMs, energy and food typically account for a higher share of household spending than in developed markets. So emerging markets will be more vulnerable to this increase in inflationary pressure.

India is particularly vulnerable with food accounting for over 50 percent of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket. It’s20-40 percent of the CPI basket for many EMs.

By contrast, commodity exporting EMs are relatively better positioned. Broadly speaking, these nation states are in Latin America and the Middle East; but in Asia, countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia also stand to benefit.

The second channel that includes disrupted trade, supply chains and remittances will weigh on the outlook for EMs. We anticipate some deceleration in growth into the second half of this year as inventory rebuilding eases off amid the ongoing post-COVID consumption shift from goods to services.

In certain sectors, we may see pressure on margins as businesses struggle to pass on higher input costs in a weaker demand environment.

The third set of factors, which is arguably the most worrisome element for EMs, are waning business confidence and heightened investor uncertainty, as these will weigh on asset prices, tighten financial conditions and potentially spur capital outflows.

Short-term public debt servicing will become a growing concern, particularly given that inflation is on the rise and developing countries (excluding China) are already weighed down by an estimated US$ 1 trillion debt burden.

Issues such as high corporate leverage and rising household debt, which receded during the pandemic, will likely resurface as policies tighten in emerging markets. As a result, many developing middle income countries with large debt service to export ratios are scurrying to the IMF – either to renegotiate existing deals (Pakistan and Egypt, for example) or enter into new programmes (e.g. Sri Lanka).

The US Federal Reserve may be more gradual in tightening policy but it is likely to be raising rates in an environment of weaker global growth.

It’s too soon to predict the degree to which the war in Ukraine will alter the global economic outlook but it’s already clear that the recovery will be painfully slow.

Leave a comment