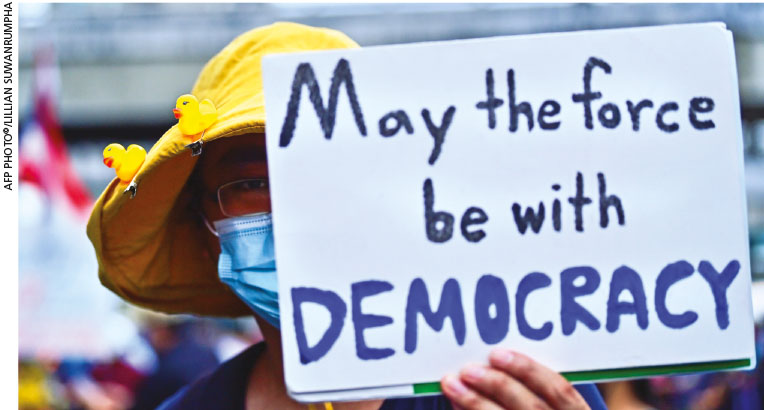

GLOBAL DEMOCRACY

DEMOS-CHAOS IN THE MAKING

Sandesh Bartlett uncovers why democracies are ailing in the present day

A lexis of words including ‘strong,’ ‘independent,’ ‘disciplined’ and ‘no-nonsense’ has quickly gained currency over the years in relation to political leadership at the executive level. Often, this has come at the expense of a cornerstone of democratic governance: the decentralisation of power.

This sudden disillusionment with democracy – the nitpicking of its foibles – undoes the centuries of strife and hardship that brought it to the fore. In the East, democracy has been rebranded as a ‘Western’ or ‘neocolonial’ concept – wrongly, in my opinion – whereas in the West, democratic processes have begun to be interpreted as inadequate.

The reason for this sudden lapse of faith in democracy is troubling and warrants analysis.

Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, in their book How Democracies Die, argue that unlike in the past when democratic norms saw a swift end due to bloody military coup d’états, democracies today are more likely to come to an end due to elected officials – a less destructive modus operandi, which is just as successful.

Maintaining a semblance of democracy is the surest weapon elected officials have to chip away at its foundations; they maintain a sense of legality by passing reforms through the legislature and approving by way of courts, while hoodwinking the general public by claiming that such attempts will make the nation more democratic through the eradication of corruption, and the increased efficiency of the state apparatus, judiciary and electoral process.

Levitsky and Ziblatt note that the method rarely alarms the general public that their democratic laws are being gradually eviscerated and replaced by dictatorships due to the absence of a ‘single moment’ such as a coup or martial law as was commonplace in the past.

Legitimate dissent or public concern is simply ignored, or treated as querulous chatter. This is why Asian leaders are likely to dismiss human rights for example, as being incorrectly Western.

In his analysis of Levitsky and Ziblatt, Mahfuz Anam notes that there are four indicators of how elected officials subvert the process. They may reject democratic rules, deny the democratic legitimacy of the opposition, tolerate violence and show a readiness to curtail civil liberties.

This is usually done gradually enough to be imperceptible but with adequate swiftness to be a killing stroke.

Charles Edel, writing for Foreign Policy from the context of the West, notes that the sudden wane in democratic thought is part of a three-pronged interconnected crisis.

He points to the continuous assault on democratic norms and values eroding social fabrics, the sense of displacement and despair among the public who feel democratic governance is unresponsive to their needs and interests, and the onslaught of non-democratic powers in Beijing and Moscow using technology to sow discord and exacerbate preexisting tensions within democratic societies.

Mature Western democracies have become polarised, corrupt and intolerant, while suffocating from internal and external threats.

This offers autocratic regimes a chance to leverage their brand of governance in spite of regressive policies and poor diplomacy as credible in exchange for valuable hallmarks of democracy, leading to democratic recession – a stark contrast to the post-Cold War impetus that saw several previously closed societies join the international order.

To make matters worse, the loss of confidence in democracy doesn’t seem to be at an end. A 2020 study found that democratic dissatisfaction was at its highest in 25 years with the UK and US recording the highest in levels of dissatisfaction, and more youth feeling disillusioned.

As such, preventing the dismantling of what has taken governance centuries to achieve is imperative.

Brian Klaas, writing for the Washington Post, notes that the first approach would be to ensure that the politicisation and malleability of the law is impossible through thorough constitutional amendment; the past decade has seen leaders from both the East and West come into power, and pass legislation that placed them above the legal system.

Second is the tightening of the election system, and its preservation from both internal attempts to undermine it (as was the case with President Donald Trump’s 2020 defeat) and external approaches to damage universal franchise, whether by external parties such as China and Russia using technology to mislead US voters.

While this approach written primarily for the American political system may not be the one-size-fits-all panacea democracies around the world require, it does offer a helpful indication of where to begin – especially considering the vulnerabilities of democracies presented by Edel, Levitsky and Ziblatt.

Voters are in imminent danger of wilfully surrendering their democratic norms and human rights to elected officials under various pretexts. This quick erosion of democratic norms requires redress.