G20 SUMMIT REPORT

A COMMITMENT TO GLOBAL GROWTH

Samantha Amerasinghe wonders whether the G20 summit delivered the goods

Today, eight years after the global financial crisis, the world economy finds itself at another critical juncture. Facing multiple risks – and challenges such as weak growth momentum, sluggish demand, volatility in financial markets, and slow growth in trade and investment – expectations were high, as G20 leaders assembled in Hangzhou, China, in September, to assess global trends, and coordinate economic and financial policies.

This year’s G20 summit was held in the wake of Brexit, rising protectionist sentiment in the US, and increasing political tensions and conflicts in Asia, Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Expectations for the meeting were higher than in recent years, given that China chaired the G20 summit for the first time, and due to its rising importance in multilateral cooperation.

The G20 concluded on a sullen note, however: there were aspiring declarations and pledges to boost global growth, but little agreement about how to do so. So was it a case of ‘more symbolism than substance;’ or were there positive developments?

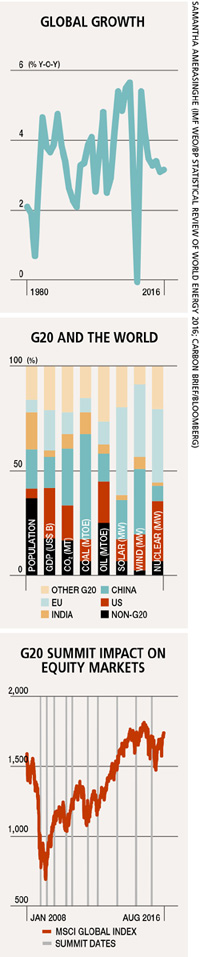

Comprising 19 countries – both emerging and developed – and the EU (in addition to Germany, France, Italy and the UK), the G20 accounts for approximately 85 percent of global GDP and 65 percent of the world’s population.

When the G20 summit was established, it was hailed as a success for its coordinated response to the global financial crisis of 2008/09. At the time, it was essential for both developed and emerging countries to work together, to restore financial market stability and boost growth.

However, the growing emphasis on long-term goals and blueprints, and an even wider set of objectives – both financial as well as non-financial (such as climate change, green energy and anti-corruption) – have made it difficult to measure its success.

This is why the forum’s relevance and usefulness continue to be closely scrutinised.

Unfortunately, the world cannot afford symbolism without real action. International Monetary Fund (IMF) Managing Director Christine Lagarde called on global leaders to take “forceful” action to revive the world economy, which continues to be stuck in low gear. This is not surprising, as global economic growth has stagnated for five consecutive years, below the 3.7 percent average that prevailed between 1990 and 2007.

Following Brexit, the IMF adjusted its global GDP forecast downward to 3.1 percent for this year, and 3.4 percent for 2017. The US economy may have recovered to 10 percent above its pre-2008 crisis peak, but the Eurozone, China and so-called BRICS do not inspire much optimism, with the possible exception of India.

Lagarde warned of a “low-growth trap,” accompanied by rising inequality that has led to increasing populism and mounting trade barriers.

As expected, G20 leaders reiterated their commitment to boosting growth through the use of all policy tools – i.e. monetary, fiscal and structural. The communiqué reaffirmed the G20 leaders’ commitment to avoiding currency wars and competitive devaluations, but these are increasingly viewed as platitudes, in a world engaged in unconventional monetary policy.

Brexit, trade deals, tax avoidance, climate change and the migrant crisis in Europe were also discussed at the forum, highlighting the divergence in objectives of G20 nations – and indeed, the challenges they face in reaching achievable solutions.

A major criticism of the G20 is that it seems to be effective during times of crisis (such as immediately following the global financial crisis), but appears less impactful in times of normalcy. This also stems from the diverse stages of development and objectives of its members. The most common criticism is that it has no legal standing, and thus no real powers to implement or monitor decisions made, which are then implemented at national level.

G20 leaders reiterated their “opposition to protectionism on trade and investment in all its forms.” This comes at an interesting time, ahead of the US presidential election, where both front-line candidates have adopted a more protectionist stance on global trade.

The communiqué included a commitment to ratify World Trade Organization (WTO) trade facilitation agreements by member states before the end of this year. The lack of any concrete plans from China on using its ‘One Belt, One Road’ and other similar initiatives to boost trade and global growth was the chief disappointment.

Yet, there were some positive developments; and they are worth highlighting.

The most notable achievement of this year’s G20 summit might be the joint announcement by the US and China that their governments have ratified the Paris Agreement on climate change, which paves the way for a wider agreement on more sustainable growth. This is a major breakthrough in the United Nations’ (UN’s) efforts to combat climate change, because the two countries, together, produce nearly 38 percent of the world’s carbon emissions.

Another positive step was the decision by President Barack Obama to institute a forum to examine excess capacity, particularly in the steel sector. This is a validation of the basic principle that supply imbalances are not only the result of market forces, but an outcome of policy decisions that are distorting a well-functioning market.

So overall, some good has come of the G20 summit.