FED POLICY

BANKING TURMOIL IN THE US

Samantha Amerasinghe reports on the recent turmoil in the US banking sector

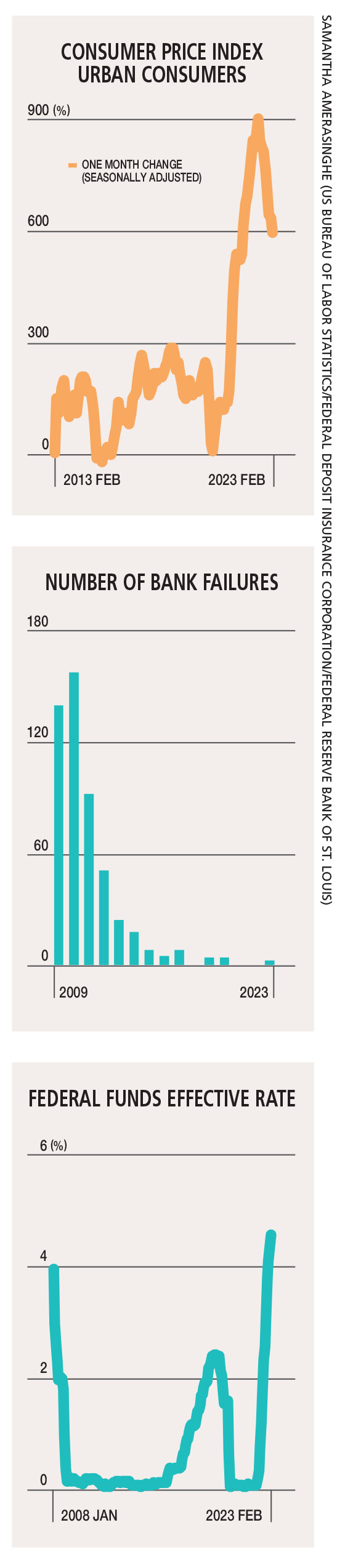

It’s an interesting time to revisit US Federal Reserve policy given the recent turmoil in the banking sector. The failure of two US regional banks – Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank, in what has been described as the largest sector meltdown since 2008 – has aided the central bank’s mission against inflation by tightening financial conditions.

This has spooked markets, and compelled investors and policy makers to reprice how much further the Fed will need to act to pursue its policy goals.

In its effort to fight inflation over the past year, the Fed raised the Federal Funds Effective Rate (FEDFUNDS) short-term interest rate in March from 0.25 percent to 4.75 percent – the highest since 2007.

Critics have blamed the Federal Reserve’s relentless rate hikes for contributing to the failure of these banks. The persistent rate increases resulted in investment losses, which in turn led to a run on the banks as depositors withdrew their funds.

Although higher interest rates played a significant role however, the sudden collapse of these two banks was primarily attributed to poor management practices. SVB’s inability to hedge or effectively navigate the well telegraphed increases in interest rates over the past year raises a host of serious regulatory, compliance and risk management questions.

Chairman of the Federal Reserve Jerome Powell has voiced confidence in the stability of the US financial system and asserted that these banks failed due to poor management rather than a generic weakness in the banking sector.

Nevertheless, Powell did acknowledge that the collapse was due to a breakdown of central bank supervision that needed to be fixed, and said new rules and regulations, as well as changes to the US deposit insurance programme, may be needed.

Market observers and investors are speculating that the Fed’s 25 basis point interest rate rise at the March policy meeting may well be the last in its campaign to bring down inflation as the central bank’s mission to tighten financial conditions has been aided by the recent turn of events, which include the failure of the two US banks and a rescue deal for Credit Suisse.

Tougher lending conditions will prevail with financial institutions expected to pull back credit lines increasingly to shore up their own balance sheets.

So can we expect the Fed to pause? And how likely are we to see further tightening at the next policy meeting?

Markets are not excluding the possibility of another 25 basis point rise in May. But a hold followed by a series of cuts later in the year is being seen as the most likely scenario.

Anxiety in the banking sector, which has already dampened banks’ willingness to lend, is likely to continue for some time. US corporate debt and equity issuance has slowed down, and fears of a dramatic slowdown in mortgage lending – particularly in commercial real estate, which is driven primarily by regional banks – have multiplied.

Banks’ lending has been impacted by funding costs, and the declining value of assets and regulatory scrutiny. This banking crisis has amplified the effects of tightening credit conditions, which the Fed had already put in place. It implies that the central bank may not need to raise borrowing costs as aggressively as anticipated because the markets will do the same work as policy rate tightening.

Economists are concerned that by prolonging its aggressive tightening programme, the Fed risks triggering a more pronounced economic downturn than is necessary as well as instability in financial markets.

Some central bank watchers caution that recent troubles in the UK government’s bond market, which required the Bank of England to step in, are a warning signal.

Powell will be under pressure to reassure economists and investors that slowing the pace of rate rises doesn’t mean a reduced commitment to bringing inflation down. A benchmark policy rate of at least five percent is now expected to be required to tame inflation.

The latest economic data suggest that monetary policy to date is yet to make a dent in inflation. However, it is important to consider the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation.

Inflation is now projected to be 3.3 percent at the end of this year, compared to 3.1 percent in the last forecast. Officials predict that the unemployment rate could be 4.5 percent (from 3.6% at the end of March) and economic growth is likely to be 0.4 percent, both of which are slightly lower than prior projections.

Unquestionably, inflation needs to come down; but with financial tightening already underway, it may wane in a sustained manner over the coming months.

If the Fed tightens further in an attempt to drive inflation down to two percent, this could be detrimental to jobs and economic growth. However, a pause could be on the horizon soon with rate cuts to follow in the summer.

Leave a comment