ECONOMIC INEQUALITY

THE GROWING GLOBAL DIVIDE

Samantha Amerasinghe evaluates the impact of COVID-19 on rising inequality

COVID-19 is worsening global economic inequality, reversing decades of progress in poverty reduction, the promotion of education, health improvements and overall wellbeing, and destroying billions of people’s livelihoods globally.

Although vaccine roll outs have offered some cause for optimism, the economic impact of the pandemic is likely to linger for many years, worsening the underlying social vulnerabilities that contribute to inequality.

Although vaccine roll outs have offered some cause for optimism, the economic impact of the pandemic is likely to linger for many years, worsening the underlying social vulnerabilities that contribute to inequality.

We assess the reasons for rising inequality, and argue that it is not an inevitable consequence of today’s technology driven economic transformations and globalisation.

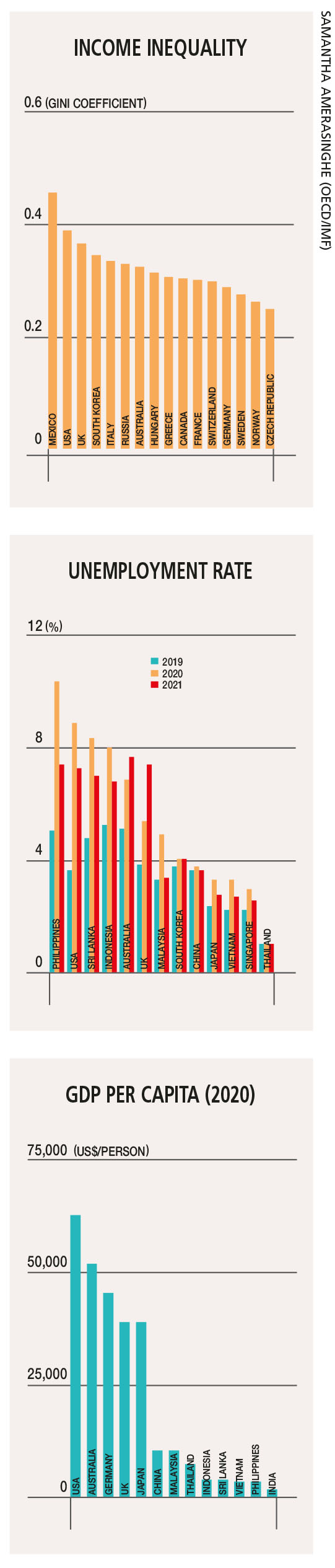

Rising inequality was a defining narrative of the 21st century long before the pandemic with adverse economic, social and political consequences.

Over time, it has depressed economic growth by dampening aggregate demand and slowing productivity growth. As COVID-19 revealed, it clearly increased societal and economic fragility with the growing risk of stoking social discontent, political polarisation and populist nationalism.

In addition, differences in regard to accessing vaccines compounded by ‘vaccine nationalism’ are set to widen the divide.

Unlike previous economic and financial crises, the restrictions on activity implemented to contain the pandemic have hit the poorest workers particularly hard, resulting in the greatest loss of global output in modern times and a sharp rise in income inequality last year.

The more vulnerable labour market groups – notably the low skilled and those employed in the hardest hit sectors, such as hospitality and retail with a high share of women, ethnic minorities, migrants and young workers – have been most impacted by job and earnings losses, which could exacerbate existing wealth inequalities.

Another concern is that the pandemic’s true economic impact is still hidden. This is because the informal economy employs about two billion workers globally with limited access to social protection and benefits. Most of these jobs are in developing countries.

The loss of income for these informal workers is among the main driving factors supporting the World Bank’s forecast that 150 million more people will be pushed into extreme poverty by next year.

According to the IMF, COVID-19 has not only exposed and increased inequalities between countries but also within them. While rich nations have been able to weather the effects of the pandemic by boosting public spending, developing countries have not had the benefit of the kind of global coordinated action evident during the 2007/08 global financial crisis.

Many developing countries entered the pandemic era with less sophisticated healthcare systems while others were affected by lost tourism revenues, lower remittances, plunging exports and soaring public debt.

Consequently, there has been greater reliance on global solidarity including the writing off of debt, increases in aid and ensuring adequate support from multilateral institutions, to address the challenges of reducing poverty and inequality.

While the poor are getting poorer, the rich are getting richer… largely due to rising asset prices.

This has been fuelled by central banks’ efforts to cushion the unprecedented slowdown in activity by pumping massive stimulus in the global economy, coupled with the success of companies (mainly in the tech industry) that experienced a demand boost resulting from the increasing dependence on cloud-based technologies, online retail, telemedicine and video-conferencing services, which have become ‘essential’ due to the shift to remote working.

This has been fuelled by central banks’ efforts to cushion the unprecedented slowdown in activity by pumping massive stimulus in the global economy, coupled with the success of companies (mainly in the tech industry) that experienced a demand boost resulting from the increasing dependence on cloud-based technologies, online retail, telemedicine and video-conferencing services, which have become ‘essential’ due to the shift to remote working.

So why is inequality rising?

A main driver of the rise in inequality is technological change. Digital technologies have been transforming markets, and how we work and do business in recent years. The increasing automation of low to middle skill jobs has shifted labour demand to higher level skills, hurting wages and jobs at the lower end of the skill spectrum.

The distribution of capital and labour has become more unequal. And COVID-19 has reinforced these inequality increasing dynamics. The pandemic induced pace of technology adoption globally risks widening the gap between rich and poor countries by shifting more investment to developed economies where automation is already established.

Although technological change has been the dominant factor, globalisation has also contributed to rising inequality within economies.

On the other hand, it has been a force for reducing inequality between economies. Emerging and developing economies have benefitted from expanding global supply chains, enabling them to narrow the income gap with developed nations.

Trade has been a critical driver, reducing the number of people in extreme poverty (i.e. living on less than US$ 1.25 a day) by half since 1990, according to the World Bank.

Nevertheless, it looks like the pandemic could disrupt this convergence with many countries looking inward to nationalist trade policy responses – including production reshoring.

Rising inequality is not an inevitable consequence of today’s technology driven economic transformations and globalisation; it is simply that policies have been too slow to respond to the challenges of change.

More inclusive economic outcomes are possible. Beyond the urgent action to contain the pandemic, and address its immediate health and economic consequences, there needs to be a longer term broader agenda to address the underlying drivers of the rise in inequality.

Redistribution – tax and transfer policies – is an important element but even more crucial is the need to better harness the potential of technological transformation. Perhaps the challenges exposed by the pandemic can be a catalyst for change.

Leave a comment