COVER STORY

EXCLUSIVE REPORT

BEYOND COVID-19

The novel coronavirus crisis and new world order that is expected to follow in its aftermath

Ever since reports of a COVID-19 outbreak in China caught the world’s attention late last year, the focus has been on efforts to mitigate the spread of the deadly virus, which has infected millions of citizens across the globe and led to around 475,000 deaths.

While some parts of the world experience a cresting of the initial coronavirus wave and a handful of nations have seemingly won the battle, there’s a debate raging about how the pandemic would serve to restructure the global order.

Some observers claim that it could lead to a decline in the US’ international clout and the dawn of a decidedly multipolar world; others warn of a global shift to greater authoritarianism with China seemingly leading from the front.

From an economic standpoint, ‘business as usual’ has been turned on its head by the coronavirus pandemic. Industries have pivoted virtually overnight in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Organisations have been compelled to take a closer look at supply chains and demand trends to work out how best to adapt at a time that calls for heightened resilience. Disruptions have also spurred many businesses to take bold measures that display a proclivity for calculated risk taking.

Corporates and industries may be bracing themselves for an uncertain future but it goes without saying that the more nimble among them will endure – as the saying goes, if there’s a will, there’s a way… there surely has to be!

In this context, this exclusive feature compiled by LMD takes an in-depth look at the wider implications of the COVID-19 pandemic both at home and further afield.

– LMD

As the world comes to terms with the fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, virtually every industry and sector has been prompted to rethink and recalibrate for a future that is likely to be vastly different to that imagined only a few months ago.

COVID-19 has had a massive impact ranging from external trade and tourism, to sectors such as agriculture, banking and finance, signalling the sheer scale of the global pandemic. Moreover, the spectre of a global recession looms large as countries look to tackle existing crises predating the latest coronavirus outbreak.

EXTERNAL TRADE As far as exports and imports go, the WTO states that trade is set to plunge as COVID-19 upends the global economy. It expects world trade to fall by between 13 and 32 percent this year. A communiqué issued by the WTO in April notes that “the decline will likely exceed the trade slump brought on by the global financial crisis of 2008/09.”

“A rapid, vigorous rebound is possible. Decisions taken now will determine the future shape of the recovery and global growth prospects… Trade will be an important ingredient here along with fiscal and monetary policy… And if countries work together, we will see a much faster recovery than if each country acts alone,” the WTO remarks.

COVID-19 has struck at the heart of global value chain hubs including China, Europe and the US. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), industrial production in China declined by 13.5 percent in January and February combined compared with the previous year.

The pandemic would have major implications for global production networks and its legacy could well last years.

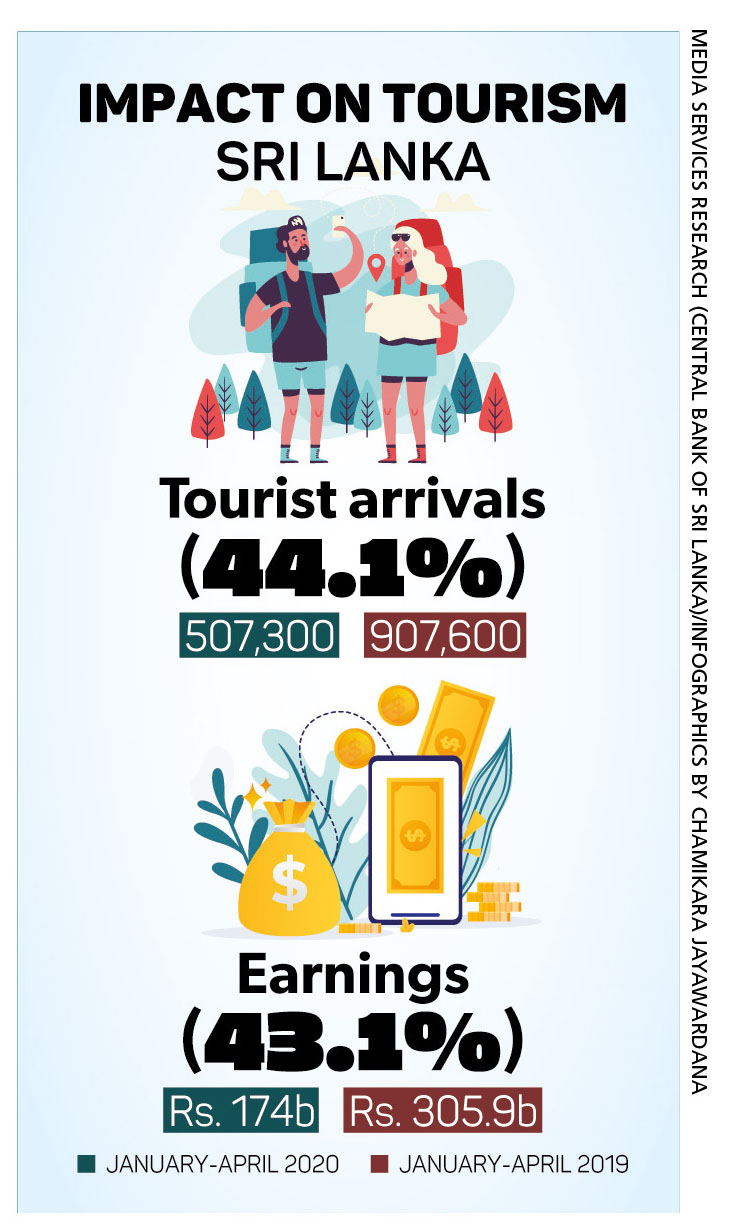

TOURISM SLUMP Several destinations continue to impose COVID-19 related travel restrictions although there have been signs in recent weeks of an easing of sorts being planned in some countries including Sri Lanka.

However, a majority of them in the Americas, the Asia-Pacific and Europe have completely closed their borders.

Indeed, travel and tourism is a major victim of the novel coronavirus with the UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) reporting that “the COVID-19 pandemic has cut international tourist arrivals in the first quarter of 2020 to a fraction of what they were a year ago.”

“Available data points to a double digit decrease of 22 percent in the first quarter of 2020 with arrivals in March down by 57 percent. This translates into a loss of 67 million international arrivals and about US$ 80 billion in receipts,” it reveals.

Given the uncertainty due to the outbreak, tourism prospects for the year have been downgraded. UNWTO points to declines of between 58 and 78 percent in international tourist arrivals for 2020, “depending on the speed of the containment, and the duration of travel restrictions and shutdown of borders.”

Small island developing states are deemed to be the most vulnerable as they’re heavily reliant on tourism – and a high magnitude shock is difficult to manage for smaller economies.

WORKER WAGES Global remittances are likely to decline sharply by about 20 percent in 2020 due to the economic crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic and shutdowns – this has been confirmed by the World Bank, which maintains that the decline “is largely due to a fall in the wages and employment of migrant workers.”

Meanwhile, Oxford Business Group asserts that the fall is expected to disproportionately affect emerging economies, which are the chief recipients of these inflows and whose citizens rely on them for basic incomes.

COVID-19 could hit the millions of dollars that migrant workers send home, which is considered vital for local communities and economies; and the disruption caused by the coronavirus could have a severe impact on remittance flows, which has also been affirmed by WEF.

FOREIGN FUNDS In shifting policy amid COVID-19, countries may adopt more restrictive policies in regard to foreign direct investment (FDI), continuing a trend of rising protectionism that began with withdrawals from trade agreements in recent years.

The World Bank explains that “in 2019, restrictions on FDI reached the highest level in 20 years.” And the latest Investment Trends Monitor of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) highlights that “the outbreak and spread of coronavirus will cause a dramatic drop in global FDI flows.”

AGRICULTURE SECTOR The impact of COVID-19 on the agriculture sector – particularly in terms of food supply and demand – requires attention to prevent food crises and the resultant negative effects on the global economy.

ILO statistics point to over a billion people worldwide with agriculture based livelihoods that remain the backbone of many low income nations.

Logistical challenges in supply chains and labour issues may prompt food supply disruptions especially if they are in place in the longer term, says the ILO: “High value and especially perishable commodities… are likely to be particularly affected.”

“The health crisis has already resulted in job destruction in sub-sectors such as floriculture… There may be a further reduction in job quality in the sector and job destruction especially at the base of the supply chain,” it adds.

In view of a potential rise in food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic, many nations and organisations are making special efforts to ensure that agriculture runs safely as an essential business, markets are well supplied (vis-à-vis affordable and nutritious food), and consumers can access and purchase food “despite movement restrictions and income losses,” according to the World Bank.

DEBT BURDEN Another area of concern is in relation to countries’ debt burdens, which are more pronounced given China’s growing influence and role as a major global lender. Estimates point to the PRC being entitled to outstanding claims of over five percent of worldwide GDP.

Research conducted by Harvard Business Review (HBR) indicates that China has extended a greater volume of loans to developing nations than previously known, creating a ‘hidden debt’ problem.

To relieve developing countries’ debt burdens amid the COVID-19 shock, the IMF cancelled debt repayments due to it from the 25 poorest developing economies – amounting to approximately US$ 215 million – in April for the following six months.

G20 leaders also announced a ‘Debt Service Suspension Initiative for Poorest Countries,’ which applies to 73 mainly low income developing nations that are eligible to borrow from the International Development Association or have been classified as least developed countries by the UN.

Estimates suggest that this initiative covers around US$ 20 billion of public debt owed to official bilateral creditors in eligible countries in 2020. But UNCTAD notes that this amounts to “a relatively small part of the long-term public and publicly guaranteed external debt stocks these countries had accumulated at the end of 2018.”

In the absence of aggressive policy action, the coronavirus pandemic could morph into a protracted debt crisis for a number of developing nations.

It is perhaps in this light that the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs’ recommendations include debt service payments being suspended to provide countries with fiscal space to respond to the crisis; debt relief being needed to avoid widespread defaults, and facilitate investments in recovery and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); and addressing gaps in the international sovereign debt restructuring architecture once the world recovers from COVID-19.

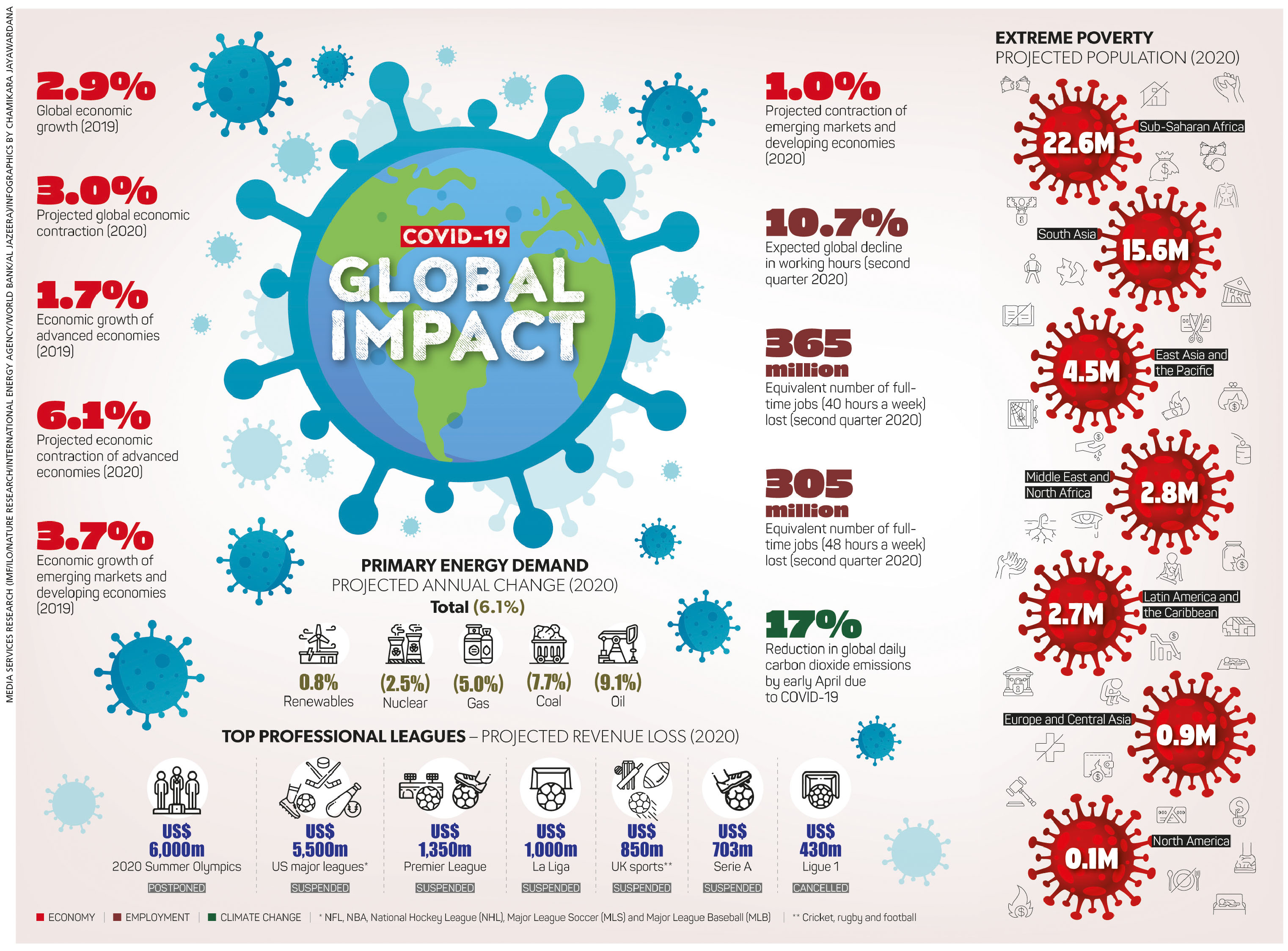

ECONOMIC GROWTH In May, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimated that the impact of COVID-19 could amount to between US$ 5.8 and 8.8 trillion (6.4-9.7% of global GDP) excluding the impact of policy measures.

This is more than double the World Bank’s April estimate of a two to four percent decline in worldwide output and higher than the IMF’s April World Economic Outlook estimate of a 6.3 percent decline in global GDP.

The ADB states that “developing Asia will weaken tremendously due to the pandemic, considering the region’s deep integration with the global economy through tourism, trade and remittances.”

“We forecast regional growth declining from 5.2 percent last year to 2.2 percent in 2020. Growth will rebound to 6.2 percent in 2021, assuming that the pandemic ends this year and activity promptly normalises,” it adds.

BANKING AND FINANCE The IMF indicates that the financial system has felt a dramatic impact with the global lending body commenting that “volatility has spiked… amid the uncertainty about the economic impact of the pandemic. With the spike in volatility, market liquidity has deteriorated significantly.”

Central banks have acted as a first line of defence in preserving financial system stability and supporting the global economy. They have looked to ease monetary policy by lowering policy rates and provided additional liquidity to the financial system.

In terms of recommendations for policy makers, WEF asserts that ‘flattening the curve’ of firm mortality must be a top priority, and governments should expand the size and scope of their support programmes.

It adds: “Governments including regulators and central banks must continue to coordinate policy on a global level to help maintain financial stability. Within countries, policy guidance must be clear and consistent across regulatory agencies … Policy makers must ensure that the financial system remains capable of safely meeting the public’s need for financial services through digital channels.”

An unprecedented global macroeconomic shock of uncertain magnitude and duration, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to “a major repricing and repositioning in global financial markets,” says the Financial Stability Board (FSB), which views pressures on credit supply to the real economy as a major concern.

Whereas the FSB finds the financial system to be more resilient and better placed to sustain financing to the real economy as a result of the G20 regulatory reforms following the financial crisis, it maintains that “financial intermediaries and markets face growing challenges in lending and funding.”

The FSB continues: “Operating financial firms in contingency mode may add to vulnerabilities … The resilience of key nodes in the global financial system is critical for financial stability.”

EMPLOYMENT PROSPECTS Job losses have become conspicuous as a result of the coronavirus outbreak with WEF reporting that two of every five jobs lost during COVID-19 may not return.

Researchers estimate that 42 percent of pandemic induced layoffs will result in a permanent loss of employment. Steven J. Davis of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business declares that “if the economic shutdown lingers for many months or if serious pandemics become a recurring phenomenon, there will be profound long-term consequences for the reallocation of jobs, workers and capital across firms and locations.”

In the US, the number of jobless claims in a two month period up to late May was over 36 million although there was better news in early June. India’s lockdown led to 120 million plus job losses in April, a majority of which were small traders and labourers. And unemployment in the UK was expected to increase by over two million by end June.

GLOBAL POVERTY According to the Brookings Institution’s post-COVID-19 estimates, some 690 million people across the world are likely to encounter extreme poverty in 2020 compared to previous estimates of 640 million.

Meanwhile, research published by the UN University World Institute for Development Economics Research warns that the economic fallout from the pandemic could raise global poverty by as much as half a billion people or eight percent of the human population – the first time that poverty has increased globally in 30 years since 1990.

A heavy toll might be exerted on Sub-Saharan Africa. The World Bank observes: “Though sub-Saharan Africa so far has been hit relatively less by the virus from a health perspective, our projections suggest that it will be the region hit hardest in terms of increased extreme poverty. Twenty-three million of the people pushed into poverty are projected to be in sub-Saharan Africa and 16 million in South Asia.”

HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS Healthcare sector infrastructure has taken centre stage during the coronavirus outbreak whether in developed nations such as the US or their developing counterparts.

At a media briefing held in May, WHO officials emphasised that gaps in public investment are undermining health and welfare around the world, and thereby putting global security and economic development at risk.

The world expends approximately US$ 7.5 trillion (or 10% of global GDP) on healthcare each year but the WHO states that “while spending has increased steadily, dangerous public health gaps exist especially in rural or conflict ridden areas where access is difficult and infrastructure is lacking.”

Examples of efforts to build more resilient healthcare systems include the WHO and European Investment Bank boosting cooperation to strengthen public health, the supply of essential equipment, training and hygiene investment in countries most vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Healthcare personnel have been on the front lines of the pandemic but there’s been a newfound appreciation for the role of other workers considered essential as well, from delivery drivers to shelf stackers.

Migrant workers have also proved invaluable during the pandemic, compelling policy makers to renew their approach to foreign labour. And there have been calls to protect the rights of and improve healthcare services for refugees, the displaced and stateless persons.

CONSUMER TRENDS Wallet adjustments based on circumstance, rebalanced fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) baskets, reassessed pricing mechanisms, reprioritised values, rising origin preferences and reset brand relationships are areas where consumption dynamics will change due to COVID-19 as identified by Nielsen; altered eating and shopping habits among consumers will also be part of the new world order.

While there has been a ubiquitous shift to e-commerce particularly during the lockdown period, signalling the dominance of online channels, Nielsen points out that physical stores are equally important.

EDUCATION REFORM Lockdowns imposed in many parts of the world meant that traditional in-class education was turned on its head and digital channels were brought to the forefront.

The temporary closure of schools is said to have impacted more than 90 percent of students worldwide (that’s some 1.6 billion children and young people) and led to wider adoption of ‘edtech’ to enable access to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research also suggests that online learning could increase the retention of information and requires less time, implying that recent changes implemented in the education sphere might be commonly applied in the future.

As more students embrace remote learning, parents – especially those with full-time occupations themselves – are also realising the value of educators in today’s world.

INNOVATIVE TECH Innovation and technological advancements have been accelerated in the wake of the coronavirus – and this is not solely in the healthcare and education domains.

The likes of China, South Korea and Taiwan are using AI, big data and other technologies to battle COVID-19. Fintech has also taken off in emerging economies, thereby offering a lifeline to crisis hit businesses.

THE ENVIRONMENT Silver linings may seem few and far between in the age of coronavirus but there are signs pointing to ecological benefits stemming from the pandemic. In fact, with many citizens of the world confined indoors, the planet may be living through one of the largest falls in carbon output on record.

As economies begin to rebuild in the aftermath of COVID-19, policy changes to combat climate change ought to be implemented with renewed vigour. These shifts may entail anything from cleaner transportation to greater opportunities for remote working in a range of disciplines.

While governments may be focussed on pandemic containment efforts, there is also an urgent need for them to reinforce environmental commitments and mobilise in acting on the climate.

WORLD RESPONSE The World Health Organization – together with national governments – has ostensibly led the fight against the pandemic. Amid a rising caseload, not all state responses have been well-received and nor has the WHO received unanimous support for its efforts.

However, what is clear is that a long-term approach that involves research funding for medical breakthroughs, and fundamentally altered lifestyles and business models, will prove vital in overcoming the complexities the world faces today.

LOCAL OUTCOMES

Zulfath Saheed examines how COVID-19 has impacted business in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka may be an island but it didn’t escape the clutches of the coronavirus pandemic, exposed as it has been to global travel and trade in recent times. When reports of ‘local cases’ of COVID-19 first emerged earlier in the year, ordinary citizens and businesses alike found themselves in a state of limbo as to how they would tackle the days and weeks ahead in the face of the unprecedented health crisis.

While the patient count has grown in the months gone by, Sri Lanka appears to have benefitted to some extent from the extended curfew and lockdowns imposed across the island – this is evidenced by its performance on the Global Response to Infectious Diseases (GRID) index where it was ranked 10th alongside the likes of Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Nevertheless, not all economic sectors and industries are equal so to speak; so from a business perspective, the coronavirus impact varies considerably depending on the sector of operation.

COMMERCIAL ACTIVITY Textiles and apparel are among the largest contributors to Sri Lanka’s export revenue. But a COVID-19 induced drop in global demand from major export destinations has meant a slowdown in new orders and employment, impacting the island’s manufacturers.

Moreover, raw material imports have faced delays on account of supply side disruptions due to the pandemic.

Experts warn of apparel industry revenue losses exceeding US$ 1 billion between March and September, which could increase further if the coronavirus continues to spread here in Sri Lanka.

The manufacturing sector as a whole was brought to a virtual standstill due to a manpower shortage prompted by the curfew. An EY report titled ‘COVID-19 Industry Market Overviews’ observes that “from end user demand to supply side disruptions and plant closures, companies are grappling with the impact and trying to understand the long-term implications.”

Furthermore, it notes that the construction industry “has been hit by an inconsistent response to site closures and significant supply chain disruption, leading to delays that are both expensive and challenging to manage.”

Tourism, agriculture and retail have also been impacted by the pandemic. According to ICRA Lanka, “tourism is the most vulnerable sector to the COVID crisis. The social distancing requirements, travel disruptions or restrictions [and] quarantine requirements will inevitably affect the global tourism industry – and hence, the local industry… The recovery of this industry will hinge largely on the recovery of key source markets.”

FINTECH REVOLUTION With the implementation of physical distancing measures and nationwide lockdowns, the financial services industry as well as consumers have shifted to digital payment channels.

Therefore, banks are expected to invest in improving digital platforms while fintech solutions are also likely to witness greater opportunity.

Mobile apps and social media based businesses have flourished during the curfew and lockdown, and cashless transactions also witnessed greater take-up owing to health concerns related to handling cash.

As the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) points out, “the current crisis may potentially create much needed impetus for the Sri Lankan economy to embrace e-commerce platforms especially through social media. Even though at times, many companies struggled to cope with the rapid increase in demand for services, they have since established systems to engage in higher rates of e-commerce.”

It states that “in a post-COVID-19 economic order, having experienced its convenience, it is likely that demand continues for companies to introduce and upgrade e-commerce tools. A broader improvement in the e-commerce ecosystem in the country therefore, would consequently result in long-term benefits to expand choice and coverage of social media based businesses.”

SMALL ENTERPRISES It is often noted that SMEs form the backbone of Sri Lanka’s economy. The informal sector also accounts for a considerable share of the country’s labour force.

However, SMEs, micro-SMEs (MSMEs) and daily wage earners have been hard hit as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. And while the state has announced relief measures targeting these groups, it is vital that the processes to obtain concessionary finance don’t discourage small businesses by their complexity.

And there’s a need to fast track disbursements of approved funding because time may soon run out for those who are depending on the relief measures for their very survival.

SINO-LANKA TIES When it comes to engaging with the world, Sri Lanka has actively sought stronger ties with China in the postwar era, so much so that a sizable chunk of the nation’s debt burden is attributed to its Far Eastern ally.

But given the origins of COVID-19 and China being the original epicentre of the outbreak, the PRC’s economy has witnessed a sharp contraction in the first quarter of 2020. Meanwhile, Sri Lanka sources a little under a fifth of its imports from China.

It follows that the Sri Lankan economy’s ability to steer itself towards a recovery would depend on how soon its trading partners regain their economic composure.

CORPORATE VIEWPOINTS Offering an expert perspective on a recent edition of LMDtv – a weekly wrap of business, which airs on our digital platforms – the Secretary General of the National Chamber of Exporters (NCE) Shiham Marikar pointed out that “even if Sri Lanka is able to fully recover, we wouldn’t be able to export until the countries buying from us recover.” He also cautioned that “challenges may persist for 12 or even 24 months and products exported by Sri Lanka may need slight adjustments going forward.”

Meanwhile, economist Deshal de Mel noted in a subsequent airing that “as a result of multiple shocks suffered since 2017, the Sri Lankan economy has been battered over the last few years, GDP growth has been well below potential and the government’s fiscal position has been affected as well.”

In terms of the immediate concern for manufacturing, the CEO of Lion Brewery Suresh Shah said on LMDtv that the sector “cannot permit unemployment figures to increase and must attempt to maintain wages although this is a difficult undertaking.”

And the Secretary General and CEO of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Manjula de Silva highlighted a ‘shared vision’ that refers to “the need for the public and private sectors to collaborate in this time of crisis, and chart a course of recovery.”

GOVERNMENT STRATEGY As for government action to boost business and investment, the World Economic Forum (WEF) maintains that the shift from ‘respond’ to ‘recover’ requires a move from an internal functional view to a view focussed on stakeholders and outcomes.

It concludes that while defining the destination first and working backwards will help leaders create more aggressive and creative plans, “the pandemic offers opportunities to act to build trust or lose it.”

– Additional reporting by Dananji Samarakoon,Lashani Ramanayake and Lourdes Abeyeratne

CORPORATE PERSPECTIVES

Sandesh Bartlett reports on insights into the business outlook in the COVID-19 aftermath

COUNTRY RATING

Q: Emerging markets are at great risk due to COVID-19. What makes Sri Lanka particularly vulnerable – and what can be done to mitigate the impact in the medium term?

A: Following [the financial crisis in] 2008, the world realised that sustaining the banking sector was crucial and printing money in this pursuit was a necessary evil.

However, unlike other countries, Sri Lanka doesn’t have the financial space to adopt such measures as its budget deficit is alarmingly high and could account for more than 10 percent of GDP this year. But a multi-pronged strategy to redress this vulnerability is possible.

Firstly, the state must push state owned enterprise (SOE) reforms. Many SOEs run at losses and while the state can cut expenditure, it must account for recurring expenditure on public sector salaries. Developing SOEs and solving inefficiencies so that at the very least, SOEs no longer run at losses would lessen the burden on taxpayers.

Secondly, the state must revitalise its investment and trade policies to increase foreign direct investments (FDI). With garments and tourism battered by COVID-19, a temporary market in the manufacture of personal protective equipment (PPE) has been found. This will only last the duration of the crisis. Going forward, Sri Lanka must diversify export markets beyond traditional confines.

Sri Lanka must also incentivise FDIs in any way possible as the inflow of foreign technology, jobs and capital will drive development across several sectors, and transport the economy to greater heights. Further infrastructure development should not be financed by government to government loans but rather, via public-private partnerships.

While many have declared the national economy to be resilient to COVID-19, this is only due to the domestic sector. Developing local industries to improve this resilience is paramount. There is room to grow, and the introduction of agricultural technologies and developments in sustainable fishing are good directions in which to begin.

Q: What policies can the state adopt to improve Sri Lanka’s ratings?

A: The Central Bank of Sri Lanka and the Ministry of Finance, managing the monetary and fiscal policies respectively, should work together in identifying the importance of ratings and managing rating drivers.

It has been broadly identified that ratings have suffered due to a growing budget deficit, and widening current account and balance of payments. Half of the total debt is domestic while the other half is external. More external debt means Sri Lanka has to find dollar revenue to service these loans, which increase the external risks.

Overall, belt tightening with lower expenditure to cut the budget deficit must follow. The economy has to recover before tax revenue can make a serious contribution. It is as important to improve the ease of doing business while diversifying trade.

With COVID-19, unfolding trade tensions between the US and China necessitating the movement of manufacture away from the latter, and the political unrest in Hong Kong, Sri Lanka has an opportunity to market the Port City (Colombo International Finance City a.k.a. CIFC).

Q: Where do you see the Sri Lankan Rupee and inflation heading, given the unfolding economic scenario? And what are the sensitivities?

A: In time, import restrictions will ebb, and the next priority for imports will be intermediate goods for value added products, and exports such as garments and latex inter alia.

Key export revenue is in decline with no visible short-term gains to suggest growth in this area. So there will be exchange pressures.

Sri Lanka must strategise to add more value to existing exports and remittances, and look at other export markets. This includes new markets beyond the EU and US, and making use of natural resources (such as marine resources), which could diversify our export offering to protect vulnerable currency and address the double deficit.

As demand for credit grows and the economy picks up momentum, inflationary pressures will mount and interest rates tighten. Much depends on how the supply side catches up as demand grows.

Maninda Wickramasinghe

CEO and Country Head

Fitch Ratings Lanka

MONETARY POLICY

Q: How is the government stimulating economic activity amid the fallout from COVID-19?

A: The spread of COVID-19 saw many sectors grind to a standstill. As production wound to a halt, incomes of those engaged therein dropped with the threat of starvation and hunger likely among the poorer strata.

While the government relief provision of Rs. 5,000 was made available to eligible persons and their families for two consecutive months, opening up the economy was necessary as the vigour of the virus reduced.

Therefore, government action to gradually open up economic activity has begun from agriculture, fisheries and related activities that are largely village based.

Beyond this, the priority has been to provide relief to employment intensive economic activities, which are amenable to quarantine rules as the poorer strata of the population find their livelihoods in these activities.

Micro SMEs (MSMEs) in agro-industry along with self-employment intensive vocations in agriculture and other related segments are being promoted; and most economic activities that are promoted are chosen based on criteria such as their contribution to employment, import savings and exports.

Which activities can be promoted depends on their ability to abide by the physical distancing measures. Therefore, some major contributors to employment, income and GDP – such as tourism and garments – remain at a standstill.

Indeed, COVID-19 could be effectively used as a turning point in the structural change of the Sri Lankan economy.

Firstly, the government’s reaction to the pandemic has brought into question the criticism of the state sector being an inefficient goliath that wastes more than it contributes to the national economy.

And secondly, the pandemic has taught us the importance of strengthening domestic production capacity in areas that could competitively produce locally – particularly, the items needed to maintain food security in the country.

Q: What other alternatives are available to the government to resuscitate financial flows and liquidity, and protect employment?

A: The months immediately prior to the onset of COVID-19 in Sri Lanka were not long enough to generate the full economic revival impact of tax concessions introduced by the president. Coronavirus related health measures – both preventive and curative – in a basically free healthcare service system required large expenditures. Relief measures were equally costly.

In the absence of substantial inflows of funds, the required expenditure to save lives could only be met by running a large budget deficit. This meant raising loans from domestic sources. Loans had to be secured basically by the Central Bank, which on the Treasury’s request raised large volumes of loans from the market.

Additionally, the Central Bank maintained its accommodative monetary policy stance that commenced in 2019. Policy interest rates were reduced three times following the virus outbreak in the country in early March and the statutory reserve requirement was reduced. These measures plus lending to the government ensured the availability of sufficient liquidity in the market.

Furthermore, the Central Bank ordered licensed commercial banks to provide a debt moratorium to businesses including self-employment activities and individually owned businesses. A subsidised loan scheme was also introduced by the Central Bank under a refinancing facility operated by the bank.

Q: Is monetary policy a safe option for the Sri Lankan economy?

A: A substantial part of policy measures introduced to address COVID-19 has been of the monetary policy variety. So far, policy rates – the Standing Deposit Facility Rate (SDFR) and Standing Lending Facility Rate (SLFR) – have been reduced by 150 basis points since the outbreak of COVID-19 in Sri Lanka [on 16 June, policy rates were reduced further].

Reduced policy rates were aimed at bringing down market interest rates and thereby reducing the cost of funds for businesses.

To provide sufficient liquidity to financial institutions, the Statutory Reserve Ratio (SRR) on commercial bank rupee deposit liabilities was reduced by one percentage point [a further reduction was announced on 16 June]. Open market operations were used to maintain a large liquidity surplus in the domestic money market to ensure sufficient liquidity for financial institutions.

However, monetary and fiscal policy alone will not be able to steer the economy in the required direction for growth and development. Implementation of the required policy reforms to address structural issues that constrain sustained growth of the economy is needed.

Deshamanya Prof. W. D. Lakshman

Governor

Central Bank of Sri Lanka

BANKING SECTOR

Q: What risks are there for the banking sector following COVID-19?

A: The modern world is faced with an unprecedented crisis in dealing with COVID-19; an invisible and seemingly invincible enemy that has caused damage across the global economy, and weakened the economic order.

As the world economy weakens, so too will key sectors of the Sri Lankan economy that anchor themselves on foreign inflows. Certain thrust segments such as tourism, wages, remittances and garments rely on foreign markets, and will be severely affected.

The banking sector as a financial intermediary will soon feel the strain of these thrust areas coming under pressure. Similarly, banks will simultaneously face the repercussions of stepping forward during the crisis to assist affected borrowers.

As banks have granted moratoriums, concessions and adjusted repayment periods, the total revenue and earnings of the sector will begin to suffer. Additionally, reduced fee income and commissions that banks have decided to not charge will add to the mounting challenges.

This in turn will affect two major ratios that dictate the health of the banking sector – viz. capital adequacy and liquid asset ratios. While most banks have managed these ratios very well in Sri Lanka, smaller banking institutions that lack a buffer to withstand the repercussions may face challenges.

Q: And what shifts can be expected as a result of the crisis in terms of how banks operate in the next six to 12 months?

A: In the medium term, we can expect a revolution in operations owing to the new normal. While there are several challenges the banking sector and the economy have faced due to COVID-19, additional opportunities have materialised.

Firstly, as a result of the crisis, both customers and companies have learned to use digital platforms. While food, transport and merchants adopted digital platforms so too did banks. Financial institutions across the board have witnessed the fruits of investing in digital platforms early.

For example, Commercial Bank’s platform Flash witnessed a rise in 20,000 accounts to 50,000 during the extended curfew, and mobile banking saw a steady and gradual growth much higher than the pre-coronavirus engagement level of 35 percent.

E-commerce has grown, and banks will witness increased demand for international payment gateways and other supporting services, which bodes well for the future. Additionally, it might have eased restrictions on cash flows; before COVID-19, the delivery of cash was restricted but today, it can be delivered to customers – and it’s likely that this will be carried into the post-COVID-19 world as well.

However, it is important to note that these developments must be preceded by sound digital security measures.

Q: Do you believe that the Saubagya Renaissance Facility is capable of protecting businesses – and if so, to what extent? Should there be further development of business protection plans or is this sufficient?

A: The government’s decision to provide the Saubagya Rs. 50 billion refinancing facility in the form of working capital for two months was a bold decision.

Making it attractive – with a lower rate of interest to meet urgent cash flow requirements such as wages, salaries and essential business expenses – was a welcome decision. It is a fairly well thought out scheme.

However, as many have noted, 50 billion rupees is not adequate and more schemes will be required.

For instance, Commercial Bank of Ceylon is engaged in discussions with external financial development institutions to provide its own Rs. 10 billion scheme to partly bridge this gap, and make funds available to assist specific sectors such as SMEs, exporters and SMEs led by women, thereby supporting the national effort to safeguard the economy.

Sivakrishnarajah Renganathan

Managing Director

Commercial Bank

INVESTMENT OUTLOOK

Q: Has COVID-19 deterred investments in Sri Lanka – if so, how?

A: The short answer is ‘yes’ – but this does not apply only to Sri Lanka. Investors – whether local or foreign – continue to revalidate their earlier strategies, plans and projections in the context of the ‘new normal’ when it comes to greenfield investments.

However, ongoing projects will largely proceed with some adjustments.

With regard to portfolio investments, there are investors both local and foreign who will make use of the sharp downward repricing of sound companies to accumulate shares or pursue acquisitions.

Since valuations tend to be depressed however, this may not be a good time for companies to raise new equity for investments.

In terms of investments in government securities issued in dollars, investors view emerging markets including Sri Lanka as being high-risk and the demand has been poor.

Therefore, it is fair to say the overall investment climate will be somewhat negative for the next three to six months until there’s greater clarity on the lockdown exit, possibility of a second wave and so on – not only in Sri Lanka but also in its major trading, tourism and export labour markets.

Another important milestone for Sri Lanka will be the settlement of the International Sovereign Bond falling due later this year.

Q: Following COVID-19, what steps can be taken for Sri Lanka to return to some degree of normalcy? How can the nation capitalise on a rebound?

A: While the post-COVID era may not witness a return to the status quo that existed prior to the pandemic, the immediate objective should be to get businesses back to pre-COVID levels of productivity as soon as possible but with higher efficiency.

Areas such as leisure and travel will take more time to recover. The apparel industry has seized the production opportunity for personal protective equipment (PPE), which should help it tide over the immediate downturn until overseas retail markets pick up.

In this situation, Sri Lanka should also consider what new industry and service segments can be ventured into instead of relying on legacy businesses. This is a good opportunity as many of our competitors have also been affected.

COVID-19 has brought into focus the importance of food security – and we can develop the agriculture and fisheries sectors, and target export markets. However, this cannot be done merely through home gardening and smallholdings. Large-scale scientific agriculture must be facilitated with downstream value addition and processing.

The work from home (WFH) and remote working culture will provide opportunities for growth in IT and communications related technology in Sri Lanka.

One of the challenges for recovery is that although the government has announced business revival support measures through the banking system, there is some way to go in terms of transferring liquidity to businesses that most need it.

This is mainly because the risk relating to revival has fallen on the banking system and at this time (mid-June), there’s no government support to the banks by way of guarantees to mitigate the credit risk of these businesses.

Going forward, Sri Lanka can position itself to be an investment destination as supply chains seek to reduce risks arising from trade tensions involving China and over-reliance on one location. However, we cannot throw tax breaks to attract investors as competitors offer them as well.

So it is paramount to make the business environment more conducive and attractive to investors in an increasingly competitive space. Labour and land use reforms, as well as speedier dispute resolution, will be critical.

Nihal Fonseka

Former member of the Monetary Board

of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka

PORT CITY

Q: What is the outlook for developing the Port City (Colombo International Finance City a.k.a. CIFC) following the economic fallout caused by COVID-19? And how about the timelines – do they remain intact?

A: The post-COVID-19 environment poses a challenging outlook for the Port City as CHEC Port City Colombo had planned its first international launch to be held this year, which understandably must now be pushed back.

However, on a positive note, this has very little impact on CHEC’s long-term ambitions for the Port City due to the project’s 25 year timeline. Therefore, in terms of how we approach the timeline, infrastructure programmes will now have to run parallel with marketing programmes – because some of the infrastructure development work scheduled for this year will be pushed pack to 2021 to coincide with realigned marketing efforts.

Ultimately, post-COVID-19, performance will depend on the Port City’s ability to attract foreign capital – and keep in mind that a project such as this has a long gestation period before it produces returns. This means we need to position Sri Lanka and the Port City with a unique proposition to grab the attention of international investors, developers, fund managers and so on.

As companies begin to recalibrate their supply chains to diversify risks and limit their dependency on any one country owing to the economic repercussions of COVID-19, investments too will be recalibrated. As a result, there will be opportunities; however, competition will also be significant.

Q: What steps has CHEC taken to ensure worker protection and job retention?

A: Despite the mass unemployment of workers spanning several industries across the globe, CHEC has not yet been forced to systematically retrench staff. Furthermore, we expect that in the long run, the Port City will be able to sustain further employment due to the 25 year length of the project.

There are detailed SOPs for office and site staff that have to be followed to ensure worker safety. At the inception, any staff returning from overseas were subject to a two week self-quarantine. Working from home was promoted and staff members were required to report to work on a roster basis. We have also provided company transport to workers who usually rely on public transport.

Additionally, other protocols such as access control and health monitoring are in place, supported by grid management for staff accommodated on-site to limit interaction between each cluster to identify and prevent any possible spread. Our teams have worked around the clock to ensure that staff members on-site have been well-informed.

Q: As countries begin to look internally and focus their efforts on the domestic landscape, will the Port City be able to attract international investors as was once hoped?

A: As mentioned previously, several countries and economies will now be forced to put their house in order, to diversify their risks and investments.

In the short term, companies will look to reduce their recurrent expenditure and protect revenue. I believe that self-sufficiency in the long term is a myth. There could be more regional partnerships and trade. This will pose opportunities and challenges alike for countries looking to attract foreign direct investments, and CHEC and Sri Lanka will have to develop the right suite of propositions that stand out to attract foreign capital.

That is why we need to closely monitor the situation and be agile in our approach to attract investment.

Thulci Aluwihare

Head of Strategy & Business Development

CHEC Port City Colombo

APPAREL INDUSTRY

Q: As a thrust industry of the Sri Lankan economy, how badly has COVID-19 affected apparel companies? Can employers retain their workforce or is unemployment a reality?

A: With the industry being one of the main thrust sectors of the national economy, it is clear that the impact is serious and threatens the survival of many companies in it.

From the onset of the pandemic, Sri Lanka was affected by several issues – beginning with China’s closure, which witnessed its supply chain being disrupted. This was followed by the impact of local operations owing to the curfew and other precautions taken to reduce the spread of the virus by the government.

The gradual closure of European and American economies, which are Sri Lanka’s two largest export markets, caused serious cash flow challenges to companies operating in the apparel industry.

While larger companies may be able to absorb any shocks such as cancellations and payment delays for a few months, SMEs may not be as resilient and their cash flows will be under increasing risk. These factors will increase the risk of unemployment, which would have social consequences as the industry is one of the largest employers in the country.

Being cognisant of the fact that the apparel industry also employs many for whom re-employment in other sectors might prove to be difficult, it is quite likely that unemployment could pose several risks for the country. The banking sector has been supportive and the apparel industry has managed cash flows as a result. However, this is only a short-term solution.

The increased demand for personal protective equipment (PPE) will hopefully open an opportunity for Sri Lanka to offset the loss of apparel products and fill untapped production capacities. This will lessen the impact of the present crisis.

We have to be hopeful that the main markets of the US and Europe will recover as soon as possible as those countries slowly begin to get back to normal.

Q: Can the apparel industry continue to look to the West following this outbreak? Are there plans to redirect Sri Lanka’s source markets to the East?

A: While there is a growing movement to diversify sources of revenue especially for national exports, I cannot predict a major change anytime in the near future.

Yes, there are opportunities in the East but Sri Lanka will have other regional markets to compete with as they will be attempting to entrench themselves in Eastern markets as well, which would result in a very competitive landscape.

Nevertheless, the US and UK markets remain the largest for apparel, and it is in the industry’s best interests that these markets recover. We will have to explore other markets; and look to find opportunities to develop new markets as well as products.

Q: Sri Lanka has long benefitted from Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP+) concessions. Could the state negotiate more international tariffs and agreements to protect what is presently a vulnerable industry?

A: If the government can negotiate preferential trade agreements that will benefit and develop Sri Lankan companies and industries, it will be most welcome.

Sri Lanka has the technical expertise and skills to capitalise on any such opportunities, and find ways to make this a successful effort.

Ranil Pathirana

Managing Director

Hirdaramani Group

TOURISM INDUSTRY

Q: What is the outlook for the tourism industry?

A: While the financial year remains bleak for the tourism industry, recent positive developments have led to a marginally improved situation than what was imagined a few months ago.

We initially believed that the industry would not yield any revenue this year but countries around the world have begun announcing plans to reopen with clear guidelines for the public.

Whether this means airports will open up as well remains to be seen. Nevertheless, it does suggest that a recovery is on the horizon. Therefore, I believe that we might begin to witness an industry pick up around December.

It is likely that the industry will be able to generate roughly 20 percent of the revenue it recorded last year, following the tourism recovery in August in the aftermath of the Easter Sunday attacks. This is a noteworthy prospect, considering that many in the industry believed there would be zero revenue at the onset of the pandemic.

Q: Is there opportunity in this crisis to reorient the tourism industry? What steps can Sri Lanka take to cater to higher yield travellers as opposed to low income backpackers?

A: As Sir Winston Churchill once remarked, “never let a good crisis go to waste.” The high end traveller promises an improved yield for the industry and there is much to be gained from reorienting Sri Lanka’s marketing strategy.

Currently, our tourism product is geared to attract backpackers with many enterprises only sporting three star hotels at best. We will need to pitch ourselves as a more high end experiential destination catering to aspects such as wellness to attract high-yield travellers.

However, contrary to popular opinion, backpackers continue to benefit tourism and local industry. While they might not contribute substantially to state revenue, their penchant for hands-on experiences has uplifted several local communities across the island.

Furthermore, they tend to be more engaged socially, and contribute significantly to the country’s publicity internationally through social media platforms such as Instagram and YouTube.

Catering to high-yield travellers will not disrupt the inflow of low yield tourists; it would simply increase the range of tourists to whom we cater. As such, we’ll need to put in place better visitor management systems for popular destinations such as national parks to manage sustainability and the influx of tourists.

Q: Is the Employers’ Federation of Ceylon’s (EFC) diktat of a minimum wage of Rs. 14,500 until tourism returns to some form of normalcy sufficient to cover the essential expenses of the workforce and their households?

A: It is important to note that the EFC salary is only a minimum wage and in truth, many people employed by larger entities are likely to be paid a higher salary.

However, there will be several smaller entities in the industry that cannot afford to pay the 14,500 rupee wage; some haven’t been able to pay salaries in May alone. As many have pointed out, this isn’t a liveable wage, which is further complicated by the fact that staff will not earn their usual supplemental incomes on which they depend such as from tips and service charges.

Considering these smaller enterprises in the industry that are less financially secure, it is unlikely that the industry as a whole can afford to pay anything higher for the next 12 months.

To make up for this loss of income, some hotels are looking at sustainable cultivation on their premises while others have resorted to food deliveries to maintain some degree of cash inflows, which will also offer staff a chance to earn supplemental income if local customers tip them.

Shiromal Cooray

Chairman

Jetwing Hotels

MIXED DEVELOPMENTS

Q: How are developers of mega projects planning to mitigate the impact of the crisis?

A: After a closure of two months due to the imposition of curfew, we resumed construction work at both projects – Cinnamon Life and TRI-ZEN – at the end of May, having strengthened our health and safety processes in line with government directives to ensure safety on-site.

We continue to work closely with medical authorities in this regard. Furthermore, we’re engaging closely with contractors in taking steps to minimise supply chain disruptions and increase productivity.

With the easing of the lockdown, we are witnessing increased interest in apartments. We’re also continuing to see interest from expat Sri Lankans who have realised that the pandemic was handled well in Sri Lanka compared to some developed countries.

Through innovative technologies such as virtual reality, we have been able to better engage with overseas customers from the comfort of their homes and encourage them to invest in our projects.

Domestic demand has also been active for residential units at the right price and we’re witnessing new entrants to the market – mainly young first time home buyers. Capitalising on this new market segment has been a conscious strategy of John Keells Properties, particularly with TRI-ZEN.

Although challenged by affordability and access to funds, this demand is expected to grow. In this regard, phasing out para tariffs on construction material imports and incentives to boost mortgage loans would be a step in the right direction to making the Sri Lankan real estate market more inclusive and competitive.

Q: What would be your perceptions on Sri Lanka’s country image at this time in the context of attracting investors? And what more needs to be done, in your view?

A: The proactive measures undertaken to address and contain the spread of COVID-19, and increased investment in healthcare and public safety measures implemented by the authorities, are commendable in bolstering the country’s resilience at this time.

There will be short-term challenges given the present situation but Sri Lanka’s underlying growth prospects in the medium to long term remain positive.

While containing the pandemic and ensuing business continuity is pivotal to attract investments, the government also needs to focus on providing further clarity on the thrust areas – i.e. those of investments in the country and ensuring a greater degree of policy consistency.

A quicker implementation process for infrastructure projects that have been planned and approved – such as the Central Expressway, elevated highways, vital power projects and port projects – is also important. In addition to overall economic growth, these projects will provide employment opportunities with spillover effects for SMEs as well.

The timing and messaging to relaunch Sri Lanka’s next tourism promotion campaign will be critical for the revival of the industry; this will help enhance its public image.

While the spread of the pandemic in Sri Lanka and source markets needs to be under control simultaneously for travel to be permitted, market research should be strengthened to identify the right target segments – both existing and emerging – and confidence in travel must be reinforced through efficient detection and testing of the virus at ports of entry.

Sri Lanka has demonstrated its ability to handle this situation exceedingly well so far.

Developing a strategic plan to drive export growth would also be vital by targeting sectors that could fast track economic recovery and growth, providing stable and consistent investments for a considerable period of time.

Promoting sustainable foreign direct investments (FDI) to Sri Lanka and leveraging on regional supply chains is another area.

Likewise, attracting FDI into sectors where MNCs are looking to develop alternate supply chains to reduce supply chain risks and disruptions, and the establishment of an Export Processing Zone (EPZ) that targets certain industries particularly in Hambantota are important.

Gihan Cooray

Deputy Chairman

Group Finance Director

John Keells Holdings

AGRICULTURE SECTOR

Q: What steps can be taken to ensure greater food security in Sri Lanka following COVID-19?

A: Firstly, it is imperative to conduct a nationwide survey assessing national food requirements. There’s no shortage of staples such as rice due to good harvests but what about other crops such as pulses, onions and potato?

If there is a clear-cut policy on how the government controls imports during the season for these crops, Sri Lanka can meet 60 percent of its requirements for these varieties of produce at the domestic level with imports only plugging gaps in production. This will subsequently reduce our reliance on imports and help protect the budget balance in the long run.

There will be challenges with regard to pulses such as lentils that cannot be grown in Sri Lanka due to climatic reasons. Therefore, in terms of the budget, the importation of this commodity must be looked at critically. As far as corn is concerned, local production costs are higher due to lower productivity compared to global standards. This means that requirements for corn in the poultry sector have to be managed in close dialogue with its stakeholders.

While Sri Lanka enjoys a variety of vegetables locally, there is a lack of data on the acreage and projected yields in some major vegetable growing zones. If these areas and the seasons in which the vegetables grow can be mapped accurately, we can solve supply and demand bottlenecks at the local level.

Ultimately, there are three initiatives that should dictate Sri Lanka’s agricultural policy: it is imperative for there to be a coherent and transparent land policy that welcomes foreign investment; policies that encourage the importation of better genetic material as well as production of high quality hybrid seed production in Sri Lanka; and policies to incentivise large companies to invest in agriculture.

Q: How can Sri Lanka improve its industrial capacity and promote domestic consumption to reduce reliance on imports? Can the crisis be used to develop an advantage in certain commodities, for example?

A: We lack an industrial raw material manufacturing base in Sri Lanka and therefore, the sector has limitations due to several inherent challenges.

The majority of the industrial capacity is in areas of low local value addition. If Sri Lanka is to industrialise further, there are potential areas to add value to spice and herb production, which is exported in raw form.

In the post-COVID-19 era, the consumption of spices and herbs will increase. As people begin to realise the value of drinking herbal products, leveraging on Sri Lankan herbs and spices could have significant export potential with value added margins as high as 200-250 percent.

Additionally, pharmaceuticals could be another industry where science knowledge workers and high skilled labour can be utilised to contribute to the global pharmaceutical industry, which could be an opportunity for future expansion.

Q: If Sri Lanka must adopt a domestic approach to basic commodities, what steps can be taken to ensure that this is done sustainably without damaging resources in the same way its neighbours have (e.g. India and fisheries)?

A: I believe that we err too much on the side of caution in regard to sustainability in Sri Lanka. It isn’t that sustainability isn’t important but rather, overemphasis is stifling economic expansion and industrial growth.

Therefore, the government should follow a clear-cut policy of zoning, which describes a policy where zones that contain virgin forests, peak wilderness and threatened fisheries are protected by the law, and other industrial zones are set up for the development of economic expansion.

This will eradicate the ambiguous process of acquiring land for development, and could breathe life into areas such as Hambantota and its airport to become industrial centres, while other zones such as national parks and forests remain fully protected.

Samantha Ranatunga

CEO

RemediumOne

LABOUR LAWS

Q: How robust is the legal framework for preventing mass unemployment? What are its limitations?

A: The robustness of the legal framework in Sri Lanka is twofold.

It has created a tier of highly protected labour – regular staff under contract who benefit from the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) and Employees’ Trust Fund (ETF) – and another tier of informal (occasionally unskilled) labour that lacks job security.

Protected labour is generally employed in large businesses and even SMEs, and benefits from the job security afforded by a highly restrictive legal framework. Consequently, this has repercussions such as low productivity, and the inability to increase wages and pay scales on a par with other economies.

As it is nearly impossible to terminate employees even if they are completely unproductive, companies have invariably been forced to account for the cost of unproductive labour by maintaining lower salary scales. Even if employers run at losses, staff cannot be made redundant to maintain profits.

The ILO states that about 66 percent of employed people in Sri Lanka work in the informal sector. This leaves a large proportion of workers threatened by job insecurity, which has a harmful effect on performance – it increases turnover and absenteeism, and undermines productivity. Our legal system thereby enables a highly unproductive workforce, which is economically damaging.

With COVID-19 forcing monumental shifts in how economies and industries operate, the threat of redundancy will increase. Sri Lanka didn’t invest in the necessary infrastructure that is pivotal to the future of work and subsequent structural deficiencies in the economy cannot effectively rectify these shortcomings.

Employers will soon find that the combined impetus of the work from home (WFH) movement and shifts to increase digitisation will render several sections of staff obsolete, and thereby leave large swathes of unproductive workers tethered to company salaries.

The inability to terminate unproductive staff will cost companies considerably in terms of responsiveness to changing market conditions, and the ability to recover and rehire new people in the future. Additionally, redundant informal workers without any income protection will create mass unemployment, a consumption slump and social disruptions.

Q: Legally speaking, what steps can be taken or laws drafted to limit the impact of COVID-19 on jobs – including remuneration and perks?

A: Businesses have cut hours and salaries to make ends meet.

Strictly speaking, this isn’t legal as staff are hired on terms of employment – and there is some degree of forced consent as staff have no other job opportunities available to them if the readjusted salary cuts and perks are not favourable. Similarly, you cannot fault employers either as they have to generate some profits to reinvest, regrow and rehire in the medium to long term.

Therefore, it might be better to bite the bullet and permit legislative changes for our inflexible labour markets to undergo the necessary developments so that companies can resize and weather COVID-19’s repercussions.

Employers have been pushing governments to recognise that the structural constraints arising from labour market inflexibility is a major factor towards Sri Lanka’s lower productivity and growth.

Failing to act now could see fewer companies recover from this crisis. The state must pass legislation on formalising the informal sector, offering it some level of job and income security without being detrimental to the needs of a flexible labour market.

Large parts of the workforce are in unproductive employment. For example, the public service is three times as large as in the UK – a country of 66 million people.

It is up to the state to change or pass new legislation to foster a flexible labour market that will be conducive to the transfer of skills to sectors where they can be more effectively employed. Developing a labour market and legal system that keeps pace with the rapidly changing conditions of the rest of the world is imperative.