CATCHY CATCHWORDS

WHEN POLITICAL SLOGANS SIMPLY AREN’T ENOUGH

BY Angelo Fernando

Let’s face it: slogans are hard to resist. We seem to love aphorisms and witty statements especially when they aptly paraphrase conventional wisdom. Flashing a slogan is akin to telegraphing what we stand for; almost like a campaign button we wear.

For instance, it’s hard to disagree with this slogan, which was a quip from former US President Ronald Reagan’s campaign: “Government’s first duty is to protect its people, not run their lives.”

For instance, it’s hard to disagree with this slogan, which was a quip from former US President Ronald Reagan’s campaign: “Government’s first duty is to protect its people, not run their lives.”

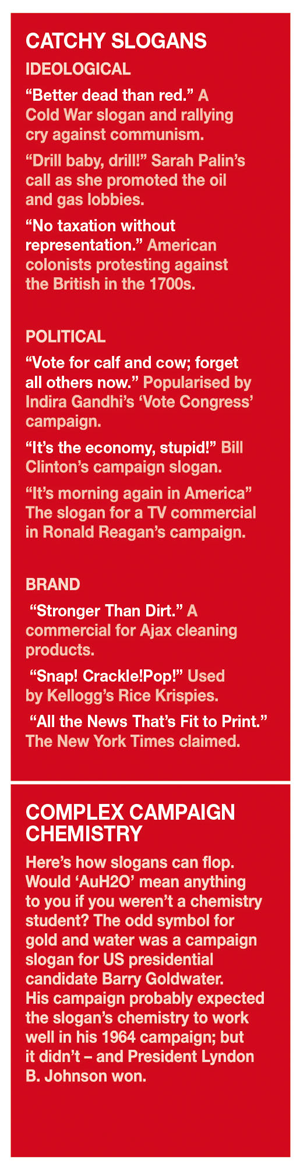

We nod our collective heads to such sentiments but the Cold War slogan – “better dead than red” – posed a troubling set of choices between nuclear annihilation and communism. It reveals the problems with slogans in general since they tend to flatten a three-dimensional issue.

While politics is rife with such oversimplification, it’s not the only place where this can be seen. In fact, marketing is the prime mover of slogans and political campaigns use marketing skills to get their messages across.

Reagan set the bar high for those who promote politicians and their ideology. Another erstwhile American President Bill Clinton’s call – “It’s Time to Change America” – wasn’t spectacular but spoke of the need for change that was concerning voters.

Today, an echo of that sentiment or a plagiarised version of it is seen in President Donald Trump’s slogan: “Make America Great Again!”

It gets worse as that slogan, which has been truncated to ‘MAGA,’ demonstrates ‘Trumpian’ flag-waving chauvinism. In sharp contrast was the four-letter word ‘Hope,’ which defined President Barack Obama’s campaign.

In 1984, the US voter heard the slogan “Where’s the beef?” Candidate Walter Mondale practically lifted it off Wendy’s hamburger chain and used it in a presidential debate with Gary Hart.

At one time in the debate, Mondale quipped that Hart’s “new ideas” were lacking substance and said: “When I hear your new ideas, I’m reminded of that ad, ‘Where’s the beef?’” That line survived and became his attack slogan.

Political slogans tend to use few words so that they can be repeated often and printed on small format media spaces. But one that went against that model stood out: “Don’t swap horses in the middle of the stream.”

The metaphor was clearly political because campaigns in America are commonly called horse races. The slogan, which was an old idiom with a down-to-earth texture, reflected the politician’s rugged individualism.

And that politician was Abraham Lincoln.

A Chinese slogan in 1956 read: “Let a hundred flowers bloom.” This had a memorable quality but backfired when it gave rise to antigovernment voices that the regime soon crushed.

Encyclopaedia Britannica cites the origin of the slogan as a reaction to “the relaxation of strict communist controls in the Soviet Union that accompanied Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of dictator Joseph Stalin.”

The slogan was a condensed version of the line: “Let a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend.” However, the voices that ‘bloomed’ weren’t exactly what the Chinese government had anticipated.

In the run-up to the 1979 general election in the UK, the Conservative Party ran on this slogan: “Labour Isn’t Working.”

Though it wasn’t simply a slogan that ushered Margaret Thatcher into power, it effectively captured the sentiment of Britain’s weariness with the Labour Party’s woes. The slogan was accompanied by images of unemployed people standing in long queues waiting for the dole.

Political slogans seem to be the only way to draw attention to the complex policies of a party or politician. The parties don’t limit their slogans to campaign season; instead, they use them to convey a message that resonates with their constituents.

It’s a hit-or-miss strategy but you can bet it’ll be around for a long time.