BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

No governmental challenge has gripped Sri Lanka more than the events between 26 October and 13 December, and the instrumentality of the judiciary in them. The people held their breath while arguments flowed and counterarguments followed.

One issue raised was whether the president has the power to supersede the authority granted to him under the constitution? The pitched battle between the executive and legislature reminded one of Cromwell against Charles I of England.

Also, if the president violates the very constitution that he promised to uphold, what hope is there for the ordinary man? Is the executive exposed to impeachment or being challenged in a court of law?

If personal views are more important than the wellbeing of the people, what is the fate of the country and its citizens?

A while ago, the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and some Western powers cast aspersions at the credibility of our judicial system. Not deeming it to be competent, they desired that foreign judges hear our human rights cases. We wonder what their views are now in the context of the unanimous judgement by seven justices of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka against the misuse of power by the executive?

The supreme court showed Sri Lankans in general and the world at large that these judges aren’t pressured by those in power. The very sovereignty of the island was at stake; not merely the whims and fancies of ambitious politicians.

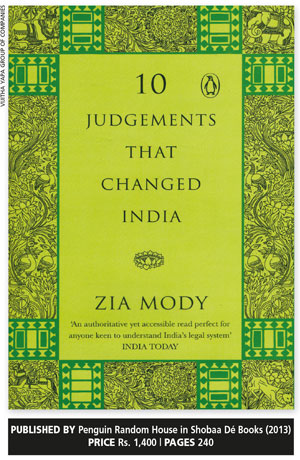

Since there are no publications in Sri Lanka about the challenges confronting the judiciary, the chronicles of neighbouring India drew my attention. Zia Mody’s 10 judgements That Changed India is one such publication wherein the supreme court had to make decisions that affected the entire subcontinent and foundations of its democracy.

Soli Sorabjee was a former Attorney General of India and is the father of the author. He says: “The common man must be made aware of, and given an understanding of the workings of the law, and the judicial process, which very often is seen as the exclusive domain of the legal profession.”

“Rather than focussing on the judgements of the court, the author has presented them in context, describing the surrounding cultural and social circumstances, and the subsequent reactions of the public and the state to each case coupled with a commendable legal analysis in language that is not legalese but reader friendly,” Sorabjee adds.

That is the value of this book. Rather than citing complex case histories, the 10 cases chosen are explained in detail along with the circumstances under which the supreme court made these judgements. The author admits it was difficult to decide which cases to leave out.

She describes the emergency rule of Indira Gandhi in the 1970s: “The court was in the throes of a constitutional conflict, torn between deciding on principles and sometimes, unfortunately bowing to political exigencies… the emergency probably taught the Supreme Court of India many hard lessons including hopefully, some it will never repeat. It also laid bare to the intelligentsia and the common man the fact that respite came from the gates of the courts.”

One of the major debates in India was whether parliament could amend fundamental rights. In Golaknath vs State of Punjab, the petitioners challenged the validity of the 1st, 4th and 17th Amendments to the constitution of India.

By a slender majority, the supreme court found fundamental rights to be so sacrosanct and transcendental that even a unanimous vote of all members of parliament would not be sufficient to weaken or undermine them.

The court also admitted that applying this decision across the board for previous constitutional amendments would lead to chaos, confusion and serious inequalities. Therefore, it decided to employ the US doctrine of ‘prospective overruling’ based on which its decision would apply only to subsequent constitutional amendments.

But parliament struck back and passed a constitutional amendment act to expressly exclude constitutional amendments from the ambit of Article 13. And parliament ensured that amendments to the constitution could once again not be reviewed by courts even if they violated the fundamental rights of citizens.

In Sri Lanka’s context, the Indian supreme court’s decision that even a unanimous vote of all MPs would not be sufficient to weaken or undermine fundamental rights reminds one of President Maithripala Sirisena’s declaration that even if all 225 MPs in parliament wanted Ranil Wickremesinghe back as prime minster, he would not allow it!

Unfortunately, space does not allow one to comment on all 10 cases that are examined in detail in this fascinating book.