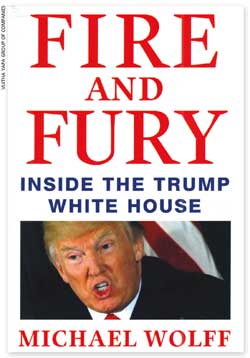

BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

No political volume in recent history has created so much interest as Fire and Fury. The book was sold out even before it was printed and the publication date was advanced due to legal strictures by US President Donald Trump’s lawyers threatening to halt its release.

No political volume in recent history has created so much interest as Fire and Fury. The book was sold out even before it was printed and the publication date was advanced due to legal strictures by US President Donald Trump’s lawyers threatening to halt its release.

News of any controversial activity by well-known personalities always creates interest – such as when President Maithripala Sirisena was reported to have walked out of a cabinet meeting, which cabinet spokesman Rajitha Senaratne explained was due to an urgent call of nature.

In his first week at the White House, Trump said: “They take everything I have ever said and exaggerate it… It’s all exaggerated. My exaggerations are exaggerated.”

Michael Wolff claims it is all dirt. For Trump critics, his real estate deals were dirty; the Trump airline was dirty; Mar-a-Lago, the golf courses and Trump hotels were dirty.

No ordinary candidate could have survived a recounting of even one of these deals, notes Wolff. “But somehow, a genial amount of corruption had been figured into the Trump candidacy. He says the platform he was running on was ‘I’ll do for you what a tough businessman does for himself.’”

The book is rehearsing what many already suspected or knew… that Trump was Trump and he wanted to assert himself. In Sri Lanka, we have several cabinet spokespersons; but in the US, there is no need for a presidential spokesman – Trump tweets and America hears.

So what are Trump’s virtues and his attractions – if any?

Piers Morgan, a media personality and Trump colleague to boot, says it’s all in the president’s book The Art of the Deal. But Trump’s co-writer Tony Schwartz claims that Trump had hardly contributed to it and may not have read all of it.

Trump’s reputation as a womaniser surfaced once again when his wife Melania didn’t join him on the president’s trip to Davos for the World Economic Forum (WEF) in late January following scurrilous allegations by a porn star.

To many of his friends, it was confounding that Trump won the election because he wholly lacked the main requirement for the job – “What neuroscientists would call executive function,” this book states – and his brain seemed incapable of performing what would be essential tasks in his new job.

Wolff explains: “He has no ability to plan and organise, and pay attention and switch focus; he had never been able to tailor his behaviour to what the goals at hand reasonably required. On the most basic level, he simply could not link cause and effect.”

According to the author, Don Jr. and Eric Trump had wondered if there couldn’t somehow be two parallel White House structures – one dedicated to their father’s big picture views and the other to handle day-to-day management issues. The two men were jokingly referred to as ‘Uday’ and ‘Qusay’ (Saddam’s sons) behind their backs.

Trump’s policies have led to uncertainty and in some cases unpredictability. But America’s reaction to North Korea differs today when compared to its response last year. Many thought then that a nuclear strike against North Korea was inevitable.

Wolff posits that there have been two reality theories for Trump politics. He argues that in one reality, which includes most of Trump’s supporters, his nature was understood and appreciated. He was the counter expert, the gut call, the everyman. The other reality was that his vices were grievous if not criminal and arose from deep-seated mental flaws.

“In this reality lived the media, which with its conclusion of a misbegotten and bastard presidency, believed it could diminish him and wound him (and wind him up), and rob him of all credibility by relentlessly pointing how literally wrong he was,” the author asserts.

Steve Bannon, a former confidant of Trump, is cited extensively in the book to reveal the realities that cost him his friendship with the president. Bannon believed Trump was never going to change and it would be better to play against rather than to the media, as its claim to be the protector of probity and factual accuracy was in itself a sham.

The exposé analyses in detail those who work with Trump. His inner circle and their temperaments are key factors in probing the presidency. But it is a pity that the book doesn’t pay attention to Trump’s foreign policy especially as regards Russia and China. The focus on domestic policies however, offers insights into how Donald Trump works, as well as his whims and fancies.

It is therefore, a reading of how a complete outsider to the global political world is changing a powerful nation’s internationally influential policies with ‘America First’ as his battle cry.