BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

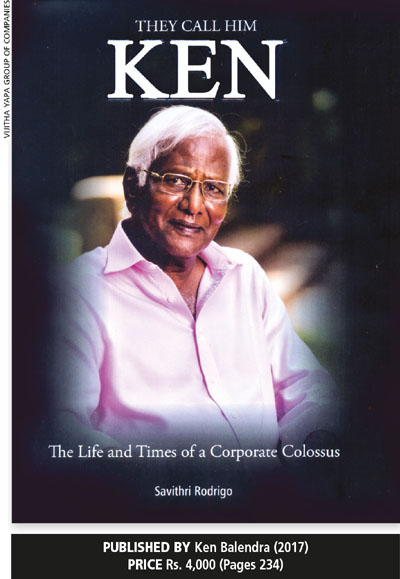

At a time when many of Sri Lanka’s best and brightest are leaving the island in search of greener pastures, the release of Deshamanya Ken Balendra’s biography is timely. His is a story of what can be achieved if one has the determination coupled with a little luck.

Born to a Tamil family, Balendra demonstrated that there are opportunities in this country, which can and must be grabbed with both hands. He is a true Sri Lankan; a person we can all be proud of.

His father worked as a clerk at the Colombo Municipal Council (CMC) and was lucky to be able to admit his children to Royal College. The family resided in Colpetty, in a tiny one bedroom house. The house was always bursting with relatives and friends from Jaffna who would visit Colombo, pop in unannounced and simply stay on. And we’re told that since the house had only one toilet, it presented “a problem of gargantuan proportions.”

The ethnic riots of 1958 brought an additional component of fear to the family when Ken’s father failed to return home after work. With the timely assistance of a friend, they found him in a refugee camp and brought him home.

Gate crashing weddings was a favourite pastime of the boys except for the minor matter of there being only one coat to share among them. So they’d operate during dining hours, spend as little time as possible at the wedding and then hand over the coat to another who was outside… so that all of them could enjoy the food. No one particularly cared about who the bride and groom were!

Ken had once visited the Colpetty fish market to be greeted by a potbellied bare bodied man who affectionately called out to him: “Ado, Bala!” He had been a childhood friend and Ken explains that “Edward had put on no little weight but had played cricket with us.”

These childhood experiences would prove useful to Balendra as he progressed in life and ended up becoming the chairman of a corporate empire. Those who forget their past have no future.

Ajith Samaranayake, the son of a vedamahattaya from the central hills who rose to become an outstanding editorial writer among other things at the Island newspaper, often spoke of a Sri Lanka sans heroes. But the life of Ken Balendra affirms that there are many Sri Lankans who were outstanding in their field and became images of inspiration; though few had the benefit of biographies to document their lives.

His entry into the tea industry was promising. The director in charge of the tea division said at the first interview that Ken was head and shoulders above the rest. Working on tea plantations with muster at 6 a.m. was a challenge. Balendra’s only weakness was his fear of snakes and adding a few pounds to the prettiest of the workers when weighing the plucked leaf.

In any autobiography or biography where the achievements of the personality are well known, I look for experiences beyond the lights and glamour because they reveal so much about the man or woman.

The company he joined was named John Keell Thompson White – though the name White was dropped soon after Balendra commenced his long stint. A friend had asked him in jest whether it was because they wanted to add Black to the name.

When John Keells began gemming operations on Pelmadulla estate where gems were found only a few feet below the ground, the brokers who came to inspect the precious stones were driving around in luxury BMWs, Toyotas and Land Rovers.

John Blacker (a British gent who was in charge of the gem venture and vice president of the company) turned a greater shade of pink when Ken asked him whether Keells would buy a super luxury vehicle to impress the buyers.

But Blacker had a better idea. The buyers had luxury cars but no white chauffer to drive the bosses around. So he suggested purchasing a spotless chauffer’s outfit and volunteered to drive Ken around!

There are details of his wonderful family and wife Swyrie – a doctor who worked at the Ratnapura hospital. When she took a year off to visit relatives in the UK, Ken tookon the babysitting duties.

Once at a holiday resort in Habarana, a shower of rain made Ken take the children out of the swimming pool for fear they may catch a cold, following which he gave them a little brandy. True to character, the spirits of the children rose with the infusion of liquid spirits.

These memories reveal the many facets of the man who was nominated LMD’s Sri Lankan Of The Year back in 1998, which are unknown to most of us. The public is familiar with his exploits as chairman of the conglomerate Deshamanya Ken Balendra created but at the same time, not much is revealed in the book about the strategies he favoured.