BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

The end of the civil war in 2009 led to a new phenomenon in Sri Lanka. Those associated with the defence establishment in the island began chronicling their experiences. Some officers such as General Kamal Gunaratne not only recorded events they had witnessed but also pointed out shortcomings of the security forces and undisciplined behaviour by several of its cadre.

This led to criticism of his writings and the likes of Minister Wimal Weerawansa cast aspersions on his bestseller titled Road to Nandikadal. Many others including Admiral of the Fleet Wasantha Karannagoda also began writing their memoirs.

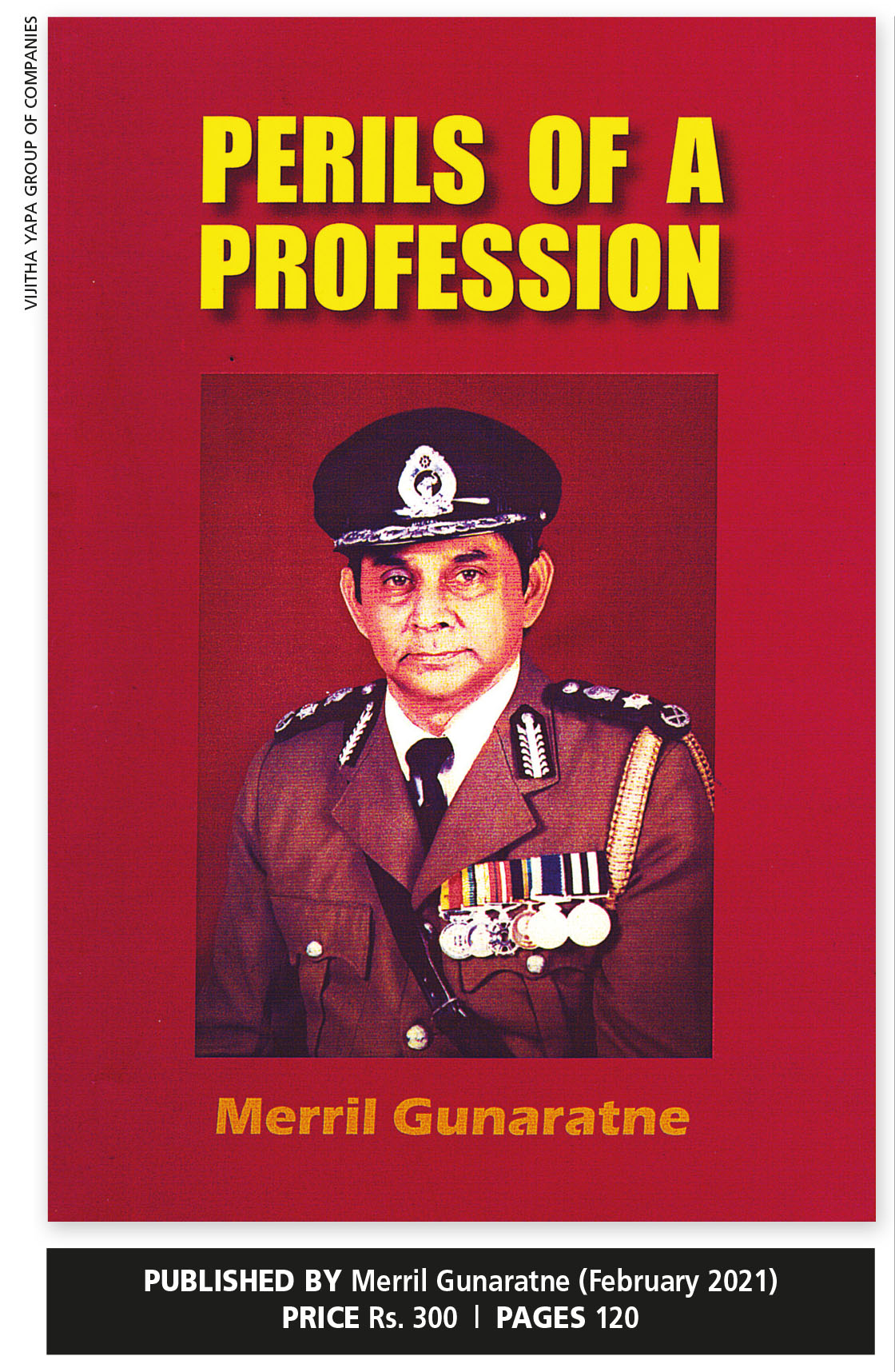

Merril Gunaratne, a former Senior Deputy Inspector General of Police – who also served many years as Director General of Intelligence and Security in the Ministry of Defence – reveals his experiences in his book Perils of a Profession.

Merril Gunaratne, a former Senior Deputy Inspector General of Police – who also served many years as Director General of Intelligence and Security in the Ministry of Defence – reveals his experiences in his book Perils of a Profession.

He feels that the integrity of the police department began to erode with the landslide victory of J. R. Jayewardene’s UNP in 1977. Politicians began to interfere with the functions of the police and many officers fell prey to those who wanted favours from them.

Nevertheless, Gunaratne asserts that despite pressure exerted by ministers such as Cyril Mathew, the firm stand taken by law enforcement officers often resulted in several of them backing down.

Having taken on some powerful politicians, the author ended up being transferred as SSP Kelaniya, which covered seven police stations. He describes how the police were summoned in many areas to protect aggressors in case the victims of their aggression made life uncomfortable for them.

“Police headquarters mysteriously abdicated responsibility to guide, direct and protect the police against such excesses,” Gunaratne claims.

The author notes with disgust that officers of the law became partners in crime with the violators because they received hardly any protection from police headquarters. Politically inspired promotions led to some officers seeking their fortunes from social patrons rather than the IGP.

His encounters with Sri Lankan presidents after 1977 are given prominence in the book. And his outspokenness on what he felt was right, which eventually led to changes of attitude, must be commended.

However, even though President Jayewardene had instructed that he be informed if politicians tried to interfere with police action, there’s no mention of JR taking action against erring MPs.

Gunaratne discusses several incidents in his book and one of these is about how the MP for Yapahuwa had abused the police in public. The author had gathered the necessary information on the MP and sent a report to the IGP, requesting that it be forwarded to JR. When the parliamentarian heard of his plans to report him to the president, he promptly apologised to the police.

In another incident, the OIC of Polgahawela Police Station was transferred and this led to protests by some MPs. But Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa stood by Gunaratne’s action and refused to cancel the transfer. Nevertheless, to appease his MPs, Premadasa transferred Gunaratne as well!

His decision to confront those who took 12 Australian staff members of Ansell Lanka hostage in 1994 during a strike and his policy when dealing with communal tension in Aluthgama are commendable. The latter is in stark contrast to the manner in which investigations into the Easter Sunday attacks were handled and shows what determined police officers can do in difficult situations.

Gunaratne had told the officers in Beruwela during the Muslim-Sinhalese riots in 1991 that if anyone wanted to sympathise with hooligans, they must shed their uniforms and join them.

He says that the police should be ashamed of how they handled the scenario in the aftermath of the Easter Sunday bombings because it’s impossible to negotiate reasonably with mobs since they are emotional at that time. He was sad to see “the police often leaning on the army to quell mob violence when such a role is indisputably in police territory.”

Dismissing ideas as old-fashioned is easy for seniors in the police force but he says it’s axiomatic that those who exist in a stagnant environment generally resist reforms. Gunaratne emphasises that the quest to identify the ills in the police department and find remedies for them requires reforms at the level of seniors in the force more than those in the lower strata.

It’s a pity the author didn’t obtain the services of an editor to streamline his memoirs. The content is disjointed and alternates haphazardly between years with no proper flow of the subject matter. As a result, a publication that could have been presented professionally has suffered.