BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

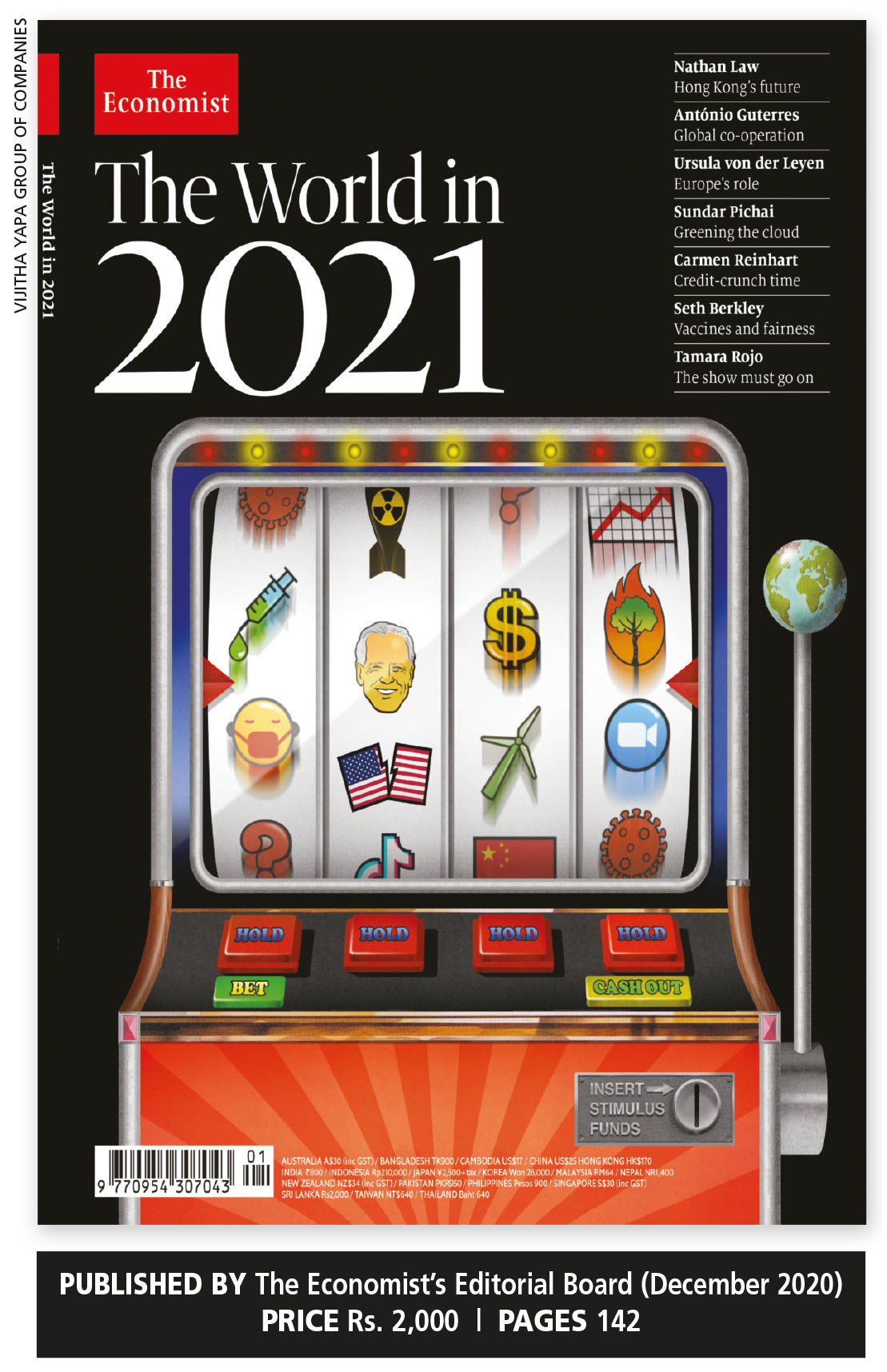

An eagerly awaited publication by The Economist that looks to the future claims that it isn’t all doom and gloom – and its first words are devoted to the COVID-19 vaccines. It believes that vaccine diplomacy will be accompanied by fights within and between countries, over who should get them and when.

Sri Lanka has been assured of vaccines for 20 percent of the population under an international initiative in which the WHO i s involved. Meanwhile, the government is seeking funding for a reported Rs. 10 billion to purchase more vaccines.

s involved. Meanwhile, the government is seeking funding for a reported Rs. 10 billion to purchase more vaccines.

The World In 2021 predicts that as economies bounce back, recovery will be patchy as local outbreaks and lockdowns come and go. Before Christmas, the UK announced that a new variant of the virus had been detected and as a result, some European countries banned flights from the United Kingdom as a precaution.

Another major issue is how US President Joe Biden will be able to patch up a crumbling rules-based international order. The Economist doesn’t expect Biden to call off the trade war with China and predicts that he will want to mend relationships with allies to wage it more effectively.

With Sri Lanka reopening the island to tourism – albeit with restrictions – the question is who will visit?

Asian countries including Sri Lanka had closed their doors to commercial flights, and applied restrictions and quarantine orders that will most probably stay in place even after COVID-19 caseloads fall. The Economist feels tourism will shrink and change shape with more emphasis being placed on domestic travel.

Editor-in-chief of The Economist Zanny Minton Beddoes feels that the pandemic has not only pummelled the global economy, it has also changed the trajectory of the three big forces that are shaping the modern world. She believes globalisation has been truncated while the digital revolution has been radically accelerated.

Beddoes also notes that migration will be much harder and remittances of foreign workers will drop, and predicts that 150 million people are likely to fall into extreme poverty by the end of 2021. The split of the digital world and its supply chains into two – one dominated by the Chinese and the other by the US – will continue.

Meanwhile, there was some noise in Sri Lanka last year about the controversial local cure for COVID-19, which its marketer claims is a cure sent by the goddess Kali. It’s worth recalling that Tanzanian President John Magufuli said his country was free of COVID-19 thanks to divine intervention even as bodies were being stacked in cemeteries at night!

Foreign Editor of The Economist Robert Guest believes the pandemic has shown that the populist tool kit of fear mongering, manufacturing scapegoats and appealing to emotions is useless against a virus that fears nothing, and doesn’t respond to divisive rhetoric. By hitting the global economy, COVID-19 has also made it harder for demagogues to keep bribing voters with their own money – especially in developing countries that don’t have access to low cost borrowing.

Australia, which holds a 20 year record of not facing a recession, is the second wealthiest nation in the world. But it seems that Australian luck has run out. Much of this prosperity had come from China; but today, the two countries are fighting over a number of issues and the list of Australian exports being boycotted by China is increasing every month.

Beef imports are banned, barley carries a large tariff, and Chinese factories have been told to stop buying Australian cotton and coal, as well as other products. Australia and New Zealand correspondent at The Economist Eleanor Whitehead says the danger is that Australia thinks it can rely on China to drive its economy while retaining the US as its most important military ally.

The Japanese fear that deflation will haunt them in 2021. And the battle for leadership continues – though at the moment, Yoshihide Suga (a loyal lieutenant of Shinzo Abe) is the prime minister.

Withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan is expected to bring major changes. The Taliban, which wants to be the dominant force in a new government, is keen to retain the inflow of international aid that is currently assisting Afghanistan’s survival.

Credit rating agencies have been downgrading Sri Lanka but it’s worth remembering that there was talk of downgrading sovereign debt to junk in India last year. Then a decision was taken to wait and see if its high rates of growth would return.

The Economist’s Mumbai bureau chief Tom Easton says that such a downgrade wouldn’t mean much in itself as India has little foreign debt but it would shake the already fragile confidence.

What a contrast to Sri Lanka and our huge foreign debt!