BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

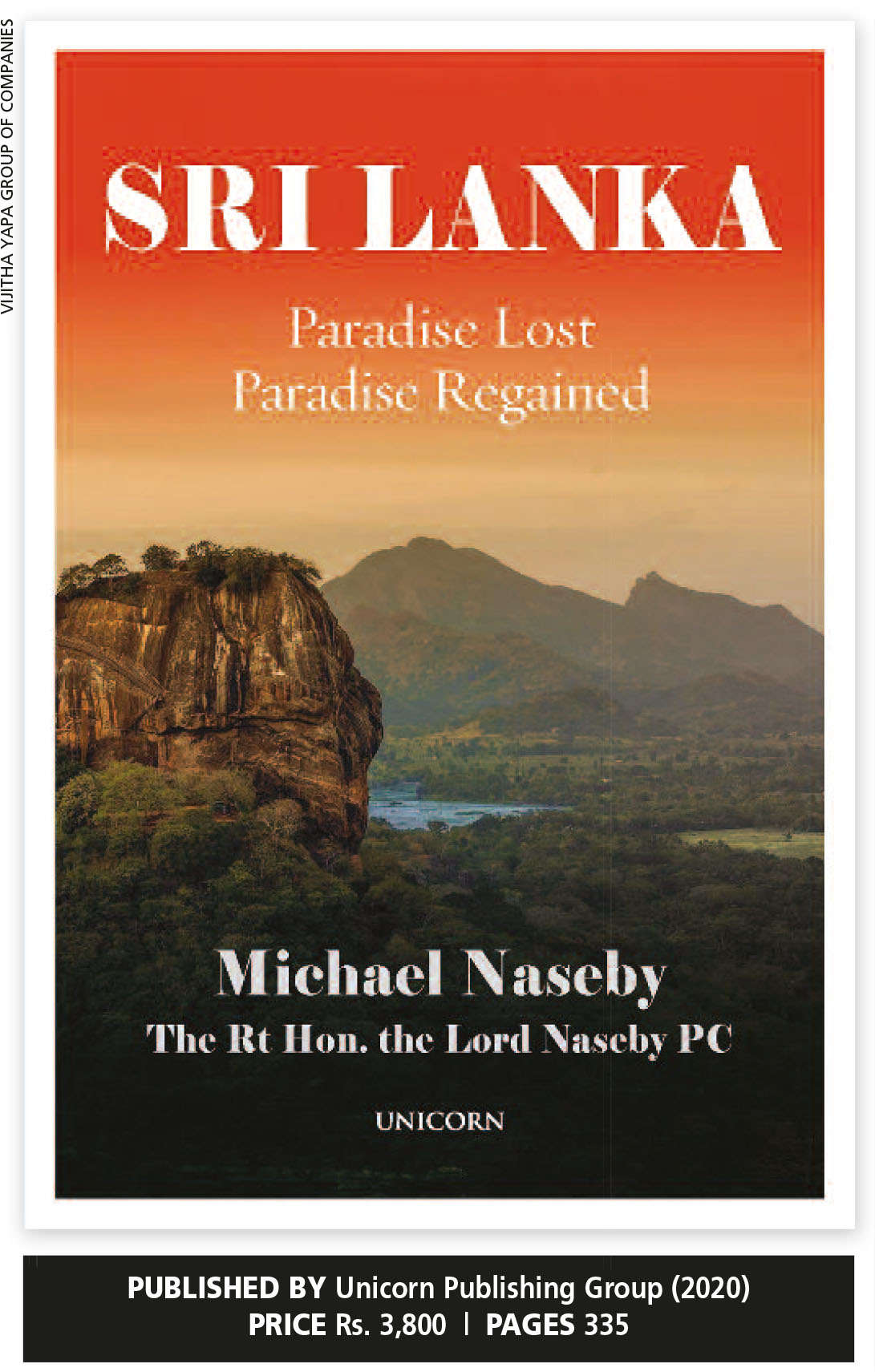

Lord Naseby (formerly Michael Morris) is well-known as an Englishman who has stood by Sri Lanka through thick and thin – he is a good friend, indeed! And at long last, he has found time to pen his memoirs and in them one learns so much about him, his political life in the UK and why he supported our country.

Former President Chandrika Kumaratunga awarded him the Sri Lanka Rathna, which is a national honour bestowed on foreigners, for his long and dedicated service to our people.

He is committed to democracy and its high principles, and chose the name Naseby when he was awarded a life peerage because the battle at Naseby in 1645 was a turning point in the First English Civil War against King Charles I.

Naseby reproduced a letter written by Oliver Cromwell to Speaker of the House of Commons William Lenthall, which praised the stand taken by the people in defeating the king’s army and dedicating their lives for the liberty of his country.

The wounded on both sides were taken to churches in Northampton and the author was proud of his association with Northampton South, which was his constituency as an MP. That’s why he chose Naseby as his name in the House of Lords.

His association with our country began 57 years ago in 1963 when he was summoned by the CEO of the Reckitt & Colman Group in Calcutta where he served as an Assistant Sales Manager. He was told that he’d been promoted to be Marketing Manager for Ceylon and had

to leave in three days as the incumbent had been accused of an illegal act.

An interesting vote count occurred when he contested as a young candidate from the Conservative Party for the Northampton South seat. He lost by about 200 votes and wanted a recount, as well as a scrutiny of the bundles. It was discovered that Tory votes were hidden inside Labour Party bundles – and Naseby won by 179 votes!

Though he was keen to organise an all party British-Sri Lanka Group in the UK’s parliament and visit the then Ceylon, his proposal didn’t receive a favourable response from our High Commissioner to the Court of St. James’s. But with the change of government in 1977, the then President J. R. Jayewardene received it with open arms.

The author played an important part in the decision taken by the British government to finance the Victoria Dam and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s visit to inaugurate it.

The book offers valuable insights into how friends in high places can help to change attitudes towards other countries. We are familiar with the influence of the old boys’ network in schools but Naseby provides fresh insights and reveals details of what friends can do.

Also forcefully presented is his view that India was wrong to interfere in Sri Lanka’s internal affairs by supporting the LTTE.

It seems that former premier Ranil Wickremesinghe didn’t take kindly to the author’s initiatives and on two occasions, refused to meet him in Sri Lanka. Norwegian peace negotiator Erik Solheim is quoted as saying: “It felt as if Ranil was not really interested in boring Norwegians who in any case did not understand anything.”

One wonders whether it was this attitude that prevented Wickremesinghe and his foreign minister Mangala Samaraweera from informing the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Geneva about the important revelations made by Naseby on the actual report prepared by the British high commission in Colombo in 2009.

This document contradicted UN spokesman in Colombo Gordon Weiss’ claims about the numbers of those killed in the last days of the war.

His discovery of reports by British high commission military attaché Lt. Col Anton Gash is the highlight of the book. Naseby managed to unearth them over a period of many years using the Freedom of Information Act.

Though many paragraphs

had been inked about this, what was eventually released paints a different picture to what had been presented to the UN.

The author’s views on NGOs makes for interesting reading. He writes: “They have become such big businesses in their own right that there is a real danger of insensitivity to the culture of a foreign country and almost a political desire to manage situations with a Western political agenda.”

Naseby has strong views on LTTE theoretician Anton Balasingham whom he had met in the UK. He describes him as “a wonderful creator of theoretical possibilities.”

While it is an interesting book, it’s a pity that it hasn’t been fact checked – there are glaring mistakes such as how the entire UNP leadership was destroyed by the LTTE bomb that killed Gamini Dissanayake and that there were trishaws in Ceylon in the early 1960s.