MIDDLE INCOME TRAP

WANTED: A NEW WAVE OF GROWTH

Taamara de Silva identifies reforms needed to avoid the middle income trap

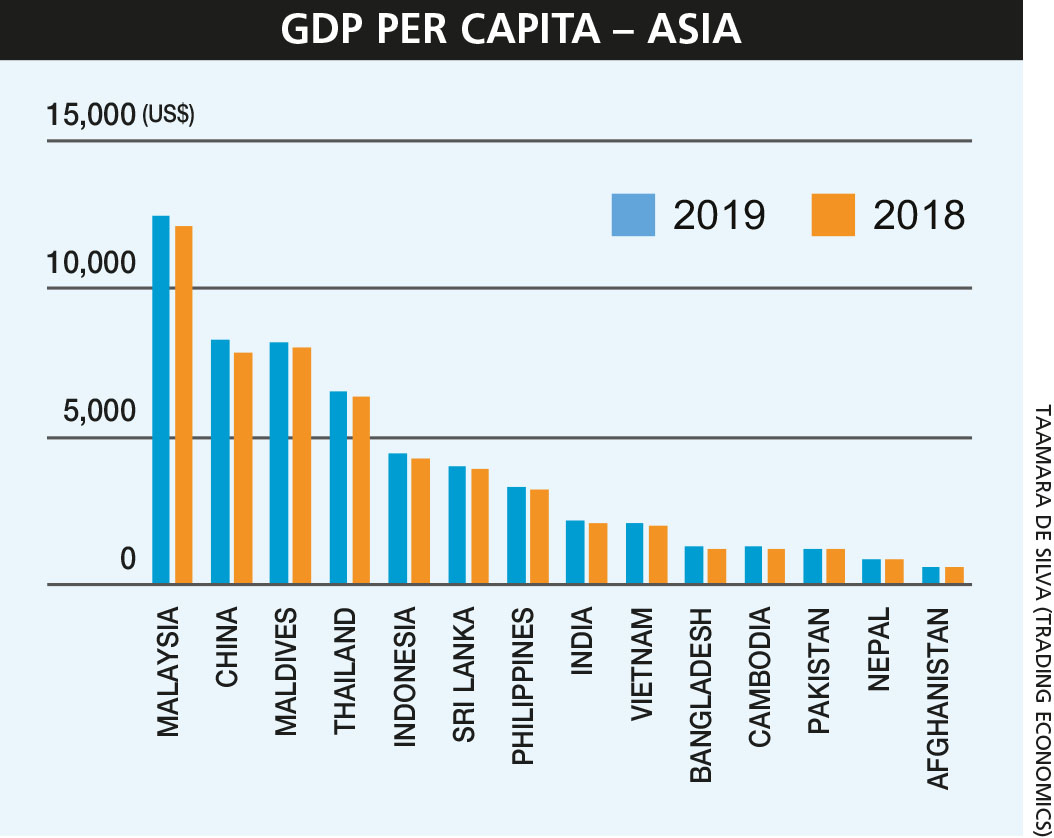

Having graduated from a lower to upper middle income economy in 2019, Sri Lanka was reclassified as a lower middle income country by the World Bank this year. This was due to its per capita income dropping from US$ 4,060 in 2019 to 4,020 dollars a year later amid real effective exchange rate and flexible inflation targeting.

Although we remain competitive in terms of per capita income compared to our regional peers, what does this reclassification hold for us as a nation?

Despite being in dire need of reconfiguring our economic and political apparatus to address key development challenges, we face the burden of managing the adverse impacts of COVID-19. A post-COVID landscape will require a novel approach – one where we anticipate consumer trends, explore growth opportunities and carefully craft strategies.

Avoiding the middle income trap will be a daunting challenge but we must strive for the synchronisation of economic and social prosperity.

Broadly defined, a middle income trap is largely the result of a country’s inability to sustain the process of moving from low to high value added industries. Generally, the advantages of low-cost labour and the imitation of foreign technology can disappear when middle and upper middle income levels are reached.

For Sri Lanka, this calls for a shift towards higher productivity sectors such as IT and manufacturing, which can create value added products and services. It also means that we must import and leverage the latest technology, and process innovation to offset the increase in rural worker wages that can potentially erode competitiveness in labour intensive industries.

Avoiding the middle income trap entails identifying strategies to introduce new processes and pinpoint new markets to maintain export growth. The personal protection equipment (PPE) segment can be one such area where we leverage our manufacturing prowess.

Ramping up domestic demand is also important as an expanding middle class can use its increasing purchasing power to purchase high quality innovative products and help drive local consumption.

Typically, countries trapped at the middle income level have low investment ratios, slow manufacturing growth, limited industrial diversification and poor labour market conditions.

Sri Lanka has its fair share of challenges. Government debt increased by Rs.1 trillion within the first half of this year. Meanwhile, foreigners remained net sellers from both capital and bond markets to the tune of 100 billion rupees by the end of June, dwarfing the outflow of Rs. 72 billion witnessed in 2019.

So what reforms might we make?

It is imperative that we grant incentives for both individuals and businesses to engage in innovation and design activities. And the enforcement of patents is essential. However, this is often lacking in developing countries including Sri Lanka. A poorly functioning system to administrate patents and enforce property rights may create a deadweight loss for the economy.

Another challenge we face is the misallocation of talent and labour market distortions, which have not only crippled growth and innovation but also increased workforce complacency. Labour market restrictions – especially retrenchment costs, pensions and compensation structures – may be particularly detrimental to design or innovation activities. After all, it is difficult to assess productivity before recruitment.

Along these lines, educational reforms may limit our scope and ability to remain competitive on a global scale. The job market of the future demands specific skills and knowledge that the higher education system may not yet be equipped to cater to in a manner that will yield immediate results.

Against the backdrop of many challenges, it is encouraging to see a visible improvement in the country’s export sector growth following the relaxation of lockdown measures, and partially due to a recovery in both domestic and global supply and demand.

Sri Lanka’s manufacturing and export base must be diversified to reverse the declining trend of exports to GDP. At the same time, widespread import restrictions have seen a massive wave of investment into locally manufactured products.

Although public resources are limited and we struggle to meet our ever increasing foreign loan repayments, the private sector has been incentivised to drive the much needed transformation of the economy through COVID-19 relief measures and subsidised loan schemes in addition to suppressed lending rates.

The government must also work to improve the investment climate, develop growth oriented infrastructure, and enhance the quality of human resources – they’re critical to catalysing domestic private investment and attracting foreign direct investment (FDI).

To ensure the inclusiveness of growth, poverty will need to be reduced further, inequality narrowed and balanced geographical development supported, if we are to overcome the middle income trap and surge ahead with a new wave of growth.